MISTAKES

There are several mistakes. I'll expand on my comments from the comments section.

- It must be clear if you are evaluating the Cauchy Principal Value of the integral. There are non-integrable singularities at $z=−a$ and $z=a$. You need two small indented contours to recover the Cauchy Principal Value integral. If $a=0$, there's a removable singularity at $z=0$, removing the need for an indented contour.

- With a semi-circle contour in the upper half plane, you can't use the Residue Theorem and "pick up" the residue at $z=a$ because of that singularity on the contour.

- You can't always assume willy-nilly an integral over a huge semi-circle in the upper half plane goes to $0$ as the circle enlarges. Unlike when $b>0$, the modulus of the integrand goes to $\infty$ in the upper half plane given $b<0$. It helps to prove why.

Fortunately, this integral is doable by evaluating its Cauchy Principal Value instead! But first, we start with some basics.

PRIMER

If $f(x)$ is continuous on $[a,\alpha)$ and $(\alpha,\infty)$ with a discontinuity of any kind at $\alpha$, then

$$

\int_{a}^\infty f(x)dx = \lim_{t\to\alpha^-}\int_a^t f(x)dx + \lim_{a\to\alpha^+}\int_u^c f(x)dx + \lim_{b\to\infty}\int_c^b f(x)dx\,,

$$

for any choice of $c>\alpha$. These limits must converge to a finite value for the improper integral to be said to converge. More details here.

You may use that statement to prove that $\int_{0}^{\infty}\frac{x\sin\left(bx\right)}{x^{2}-a^{2}}dx$ diverges. I'll leave it up to you to show that not all three limits converge.

A way to deal with divergent integrals is by introducing the Cauchy principal value, a standard method applied in mathematical applications by which an improper, and possibly divergent, integral is measured around singularities or at infinity.

The Cauchy principal value of a finite integral of a function $f$ about a point $c$ with $c \in [a,b]$ is given by

$$

\operatorname{PV} \int_a^b f(x)dx = \lim_{\epsilon\to0^+}\left(\int_a^{c-\epsilon}f(x)dx+\int_{c+\epsilon}^bf(x)dx\right)\,.

$$

More details here.

With these statements in mind, we are ready to solve the problem!

CLAIM

Let $a,b>0$. Then

$$

\operatorname{PV}\int_{0}^{\infty}\frac{x\sin\left(bx\right)}{x^{2}-a^{2}}dx = \frac{\pi}{2}\cos\left(ab\right)\,.

$$

PROOF

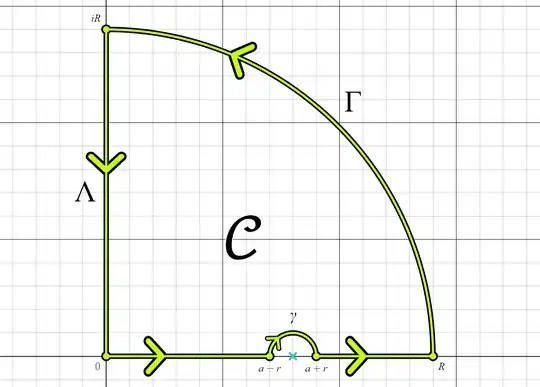

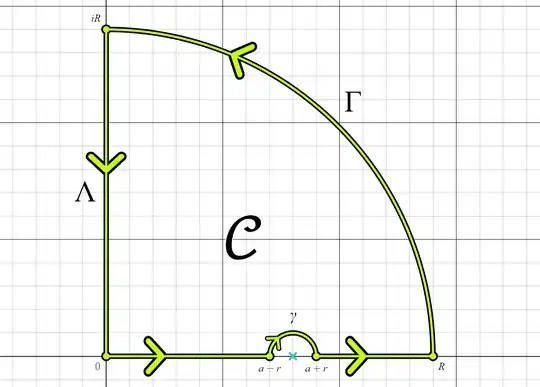

Define a holomorphic function $f: \mathbb{C}\setminus\left\{a,-a\right\} \to \mathbb{C}$ where $z \mapsto \frac{ze^{ibz}}{z^{2}-a^{2}}$. We construct a contour $\mathcal{C} = [0,a-r] \cup \gamma \cup [a+r,R] \cup \Gamma \cup \Lambda$ where

$$

\begin{align}

\gamma &= \left\{t \in [0,\pi]: a-re^{-it} \in \mathbb{C}\right\} \\

\Gamma &= \left\{t \in \left[0,\frac{\pi}{2}\right]: Re^{it} \in \mathbb{C}\right\} \\

\Lambda &= \left\{t \in [-R,0]: -Ri \in \mathbb{C}\right\}\,. \\

\end{align}

$$

Here is a visual down below and an animation here.

$$

\text{Figure 1: Contour $\mathcal{C}$ Traveling Clockwise}

$$

We write the contour integral as

$$

\oint_{\mathcal{C}}f = \int_0^{a-r}f + \int_{\gamma}f + \int_{a+r}^Rf + \int_{\Gamma}f + \int_{\Lambda}f\,,

$$

provided $R \gg a+r$. We write $\int_{\gamma}f = -\int_{\gamma_{-}}f$ where we denote $\gamma_{-}$ as the same contour but traveling counterclockwise instead.

By the Cauchy Integral Theorem, since $f$ is analytic on and inside the simple closed contour $\mathcal{C}$, we get

$$

\oint_{\mathcal{C}}f = 0\,.

$$

Applying the appropriate limits and then equating the imaginary part on both sides, we get

$$

0 = \Im \lim_{R\to\infty}\lim_{r\to0^+}\left(\int_0^{a-r}f+\int_{a+r}^Rf\right)-\Im \lim_{r\to0^+}\int_{\gamma_{-}}f + \Im\lim_{R\to\infty}\int_{\Gamma}f + \Im\lim_{R\to\infty}\int_{\Lambda}f\,.

$$

I won't go into too many details on evaluating $\displaystyle \Im\lim_{R\to\infty}\int_{\Gamma}f$ (because I'm lazy), but to give a little start, we bound the norm of $f(z)$ like this:

$$

\left|f\left(z\right)\right|=\left|\frac{ze^{ibz}}{z^{2}-a^{2}}\right|\le\frac{\left|z\right|\left|e^{ibz}\right|}{\left|z\right|^{2}-a^{2}}\overset{z \in \Gamma}=\frac{\left|Re^{it}\right|\left|\exp\left(ibRe^{it}\right)\right|}{\left|Re^{it}\right|^{2}-a^{2}}=\frac{R}{e^{bR\sin t}\left(R^{2}-a^{2}\right)}\,.

$$

From there, you use the Estimation Lemma. I have similar examples of bounded integrals that converge to $0$ here and here I wrote a while back.

After a little work, we get

$$

\Im\lim_{R\to\infty}\int_{\Gamma}f = 0\,.

$$

Evaluating $\displaystyle \Im\lim_{R\to\infty} \int_{\Lambda}f$, we have

$$

\Im\lim_{R\to\infty} \int_{\Lambda}f = \Im\int_{-R}^{0}\frac{-ite^{-ibit}}{\left(-it\right)^{2}-a^{2}}\left(-i\right)dt = \Im\int_{-R}^{0}\frac{te^{bt}}{t^{2}+a^{2}}dt = 0\,.

$$

Going back to the contour $\mathcal{C}$, we so far have

$$

\require{cancel} 0 = \Im \lim_{R\to\infty}\lim_{r\to0^+}\left(\int_0^{a-r}f+\int_{a+r}^Rf\right)-\Im \lim_{r\to0^+}\int_{\gamma_{-}}f + \cancelto{0}{\Im\lim_{R\to\infty}\int_{\Gamma}f} + \cancelto{0}{\Im\lim_{R\to\infty}\int_{\Lambda}f}\,.

$$

Rearranging the terms and using the definition of Cauchy principal value, we get

$$

\operatorname{PV}\int_{0}^{\infty}\frac{x\sin\left(bx\right)}{x^{2}-a^{2}}dx = \Im \lim_{r\to0^+}\int_{\gamma_{-}}f\,.

$$

All that's left is to evaluate this integral. Since $\gamma_{-}$ travels counterclockwise and surrounds a simple pole $z=a$, we use Theorem 9.14 from these notes and get

$$

\Im\lim_{r\to0^+}\int_{\gamma_{-}}f = \Im i \pi \mathop{\mathrm{Res}}_{z=a}f(z) = \pi \Re \lim_{z\to a}\cancel{(z-a)}\cdot \frac{ze^{ibz}}{\cancel{\left(z-a\right)}\left(z+a\right)} = \frac{\pi}{2}\cos\left(ab\right)\,.

$$

Finally, we finish with

$$

\bbox[15px,#FFFAFA,border:5px inset #C996FD]{\operatorname{PV}\int_{0}^{\infty}\frac{x\sin\left(bx\right)}{x^{2}-a^{2}}dx = \frac{\pi}{2}\cos\left(ab\right)}

$$

and we're done!