There's been some oohing and ahhing in the science press recently over the discovery of a new formula for $\pi$ obtained as a side effect of computing amplitudes in string theory: $$\pi=4+\sum_{n=1}^\infty \frac1{n!}\left(\frac1{n+\lambda}-\frac4{2n+1}\right)\left(\frac{(2n+1)^2}{4(n+\lambda)}-n\right)_{n-1}$$

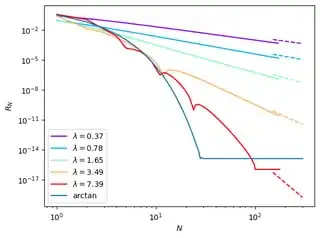

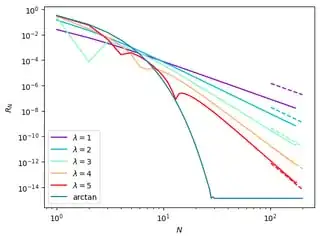

Here $(a)_b$ is the usual Pochammer symbol ($(a)_b=a(a+1)(a+2)\ldots(a+b-1)$) and $\lambda$ is a free parameter; in the large-$\lambda$ limit this becomes the classic Madhava-Leibniz formula $\pi=4\sum\frac{(-1)^n}{2n+1}$. The last term here is $\left(\frac{4(n-\lambda)+1}{4(n+\lambda)}\right)_{n-1}$; if I'm looking at it right then for large $n$ this is essentially the product of a term fairly close to $1$, a term of size roughly $\frac{2\lambda}{n+\lambda}$ (more specifically, $\frac{4(n-\lambda)-4(n+\lambda)+1}{4(n+\lambda)}$ $=\frac{1-8\lambda}{4(n+\lambda)}$), and then a set of terms coming to roughly $(n-3)!$. This would seem to suggest that the terms in the sum go as $\Theta(n^{-5})$ as $n\to\infty$: a factor of $\Theta(n^{-1})$ from the term in the first set of parentheses, a factor of $\Theta(n^{-1})$ from the $\approx\frac{2\lambda}{n+\lambda}$ term, and then a factor of $\Theta(n^{-3})$ from the $\frac{\approx(n-3)!}{n!}$ piece. That would suggest that this series converges quickly but not nearly so quickly as the various series with terms of order $c^{-n}$ that give a number of digits linearly proportional to the number of terms.

My questions are then basically: (1) Is my analysis roughly correct here, do I have the right order on terms? and (2) if not (or if so, I suppose) is this in fact a practical or competitive way to compute $\pi$? As a sort of secondary question, this formula bears at least a passing resemblance to the sort of term one might get by applying the Euler transformation to a different alternating series; is it possible that this is a transform of a known series?