I want to add the following result that maybe can be interesting:

$\textbf{Theorem.}$

If the function satisfy our condition and it is derivable at the points $0$ and $1$, then

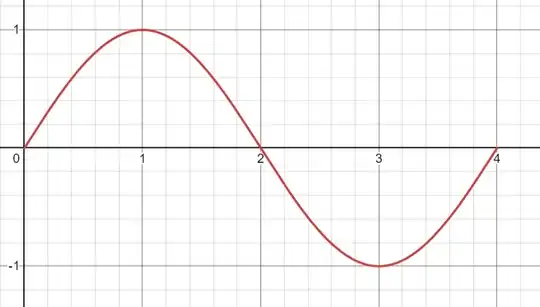

$$f(x)=\sin\left(\left(\frac{\pi}{2}+2\pi k\right)x\right), \qquad k\in \mathbb Z.$$

$\textit{Remark.}$ First of all we observe that we have three important equations

$$f(1)=f(x+(1-x))=f^2(x)+f^2(1-x), \qquad f(2x)=f(x+x)=2f(x)f(1-x)$$

and then

$$f(1)+f(2x)=\left(f(x)+f(1-x)\right)^2.$$

$\textbf{Lemma.}$ $f(0)=0$, and $f(1)=1$.

$$f(1)=f(x+(1-x))=f^2(x)+f^2(1-x), \qquad and \qquad f(2x)=f(x+x)=2f(x)f(1-x)$$

The first equation tells us $f(1)\neq 0$ otherwise f is constantly zero.

Morevoer, we use them to say

$$f(1)=f^2(1)+f^2(0), \qquad f(0)=2f(0)f(1) \implies f(1)+f(0)=(f(1)+f(0))^2$$

This means $f(1)+f(0)$ can be only $0$ or $1$.

By contradiction, if $f(1)+f(0)=0$, then we would have $f(1)=2f(1)^2$, which implies $f(1)=\frac{1}{2}$, and $f^2(0)=\frac{1}{4}$, so $f(0)=-\frac{1}{2}$.

However, $f(1)=2f^2(\frac{1}{2})$, that implies $f(\frac{1}{2})= \pm\frac{

1}{2}$, that contradicts the fact $f$ is increasing in $[0,1]$.

This forces $f(1)+f(0)=1$. By contradiction, if $f(0)\neq 0$, then we would have $f(1)=f(0)=\frac{1}{2}$, which is still not possibile.

Therefore, $f(0)=0$, and $f(1)=1$.

$\textbf{Lemma 2.}$ If $f$ is derivable at $0$ and $1$, then it is derivable everywhere, and it satisfies the Cauchy problem

$$ \begin{cases} f'(x)=f(1-x)f'(0) \\ f(0)=0, f(1)=1 \end{cases}$$

$\textit{Proof.}$ It is sufficient to observe that

$$

\frac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}=\frac{f(x)f(1-h)-f(x)+f(1-x)f(h)}{h}=f(x)\frac{f(1-h)-1}{h}+f(1-x)\frac{f(h)}{h}.

$$

Since $f(0)=0$ and $f(1)=1$, then when $h\to 0$ we obtain

$$\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(1-h)-1}{h}=-f'(1), \qquad \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(h)}{h}=f'(0).$$

Thus the derivative of $f$ at $x$ exists and it is equal to

$$f'(x)=-f(x)f'(1)+f(1-x)f'(0).$$

We observe that $f'(1)=-f'(1)+0$ so that $f'(1)=0$ and we obtain the thesis.

$\textbf{Lemma 3.}$ The function $f$ satisfies the Cauchy problem

$$ \begin{cases} f''(x)=-(f'(0))^2f(x) \\ f(0)=0, f(1)=1 \end{cases}$$

$\textit{Proof.}$ $D(f'(x))=D(f(1-x)f'(0))=-f'(1-x)f'(0)=-f(x)(f'(0))^2.$

Now we can prove the theorem:

$\textit{Proof of the theorem.}$It is easy to see that the solution of the ODE $f''(x)=-k^2f(x)$ is

$$f(x)=a\cos(kx)+b\sin(kx).$$

In our case we have

$$f(0)=0=a, \qquad f(1)=1=b \sin(k).$$

However, $k=f'(0)=bk\cos(kx)_{x=0}$, so that $b=1$ and $sin(k)=1$ implies $k=\frac{\pi}{2}+2t\pi$, $t\in\mathbb Z$ and finally

$$ f(x)=\sin\left(\left(\frac{\pi}{2}+2\pi t\right)x\right).$$

I don't actually know what happens if we do not suppose that $f$ is derivable at $0$ and $1$. If someone want to help me to find a solution, it would be nice :).