Yes these values allow to have a unique answer.

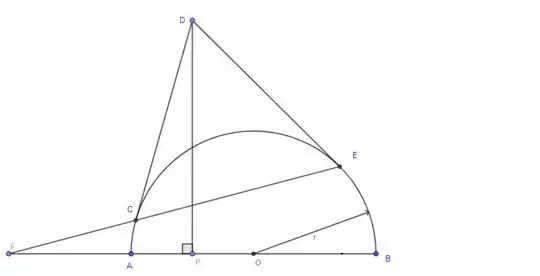

Let $G$ be the intersection of line $PD$ with the circle.

Draw the upper tangent issued from $F$ to the circle. Its point of tangency is exactly $G$ (by the duality property of polarity (See Edit below) :

$$\text{Point} \ F \ \leftrightarrow \ \text{Line} \ (F) = \text{ Line } \ PD$$

$$\text{Point} \ D \ \leftrightarrow \ \text{Line} \ (D) = \text{ Line } \ CE$$

Let us recall the important property : if the polar line of any point $M$ (here $D$) with respect to a circle passes through $N$ (here $F$) then, in a symmetrical way, the polar line of $N$ (here $F$) passes through $M$ (here $D$). Then this polar line is $PD$ and its intersection $G$ with the circle is the point of tangency.

$FG$ being a tangent in $G$, it is orthogonal to radius $OG$, which means that triangle $OGF$ is a right triangle.

If we apply in this triangle the Geometric Mean Theorem : the altitude issued from the right angle vertex is the Geometric Mean of the lengths of the sides determined by its foot on the hypotenuse, we get :

$$PG=\sqrt{PO.PF}=\sqrt{3}$$

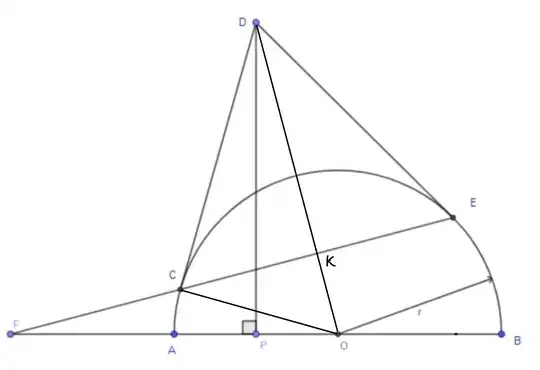

Now consider right triangle $OPG$ and apply Pythagoras to it.

Edit : In a very short way : what is polarity ?

Let us explain it wrt the unit circle. It is an "hybrid" transformation exchanging :

$$\text{Point} \ P \ \leftrightarrow \ \text{Line} \ (P)\tag{1}$$

where, in the case where $(P)$ is exterior to the circle is the line obtained by joining the two points of tangency of the tangents issued from $P$ (for example, on the figure above, the polar line of $D$ is line $CE$)

There is a parallel analytical definition, which is more general

$$\text{Point} \ P (a,b) \ \leftrightarrow \ \text{Line} \ (P) ax+by=1\tag{1'}$$

This transformation has many properties, some of them being the consequence of the following duality property :

$$\begin{cases}\text{Point} \ A \leftrightarrow \text{Line}(A)\\\text{Point} B \ \leftrightarrow \text{Line} (B)\end{cases} \ \ \ \implies \ \ \ \text{Line} \ AB \leftrightarrow \ \text{Point} \ (A) \cap (B)$$