Besides the obvious answer of an isosceles right triangle, can there be other triangles where the center of its circumscribed circle is located on the perimeter of its incircle? I tried using the Euler's theorem $d^2 = R^2 − 2Rr$ where $d=r$ By solving it I found that R/r= √2+1 which can also be determined by using cot22.5 in the isosceles right triangle but I couldn't find a way to prove or disprove that such other triangles exist.

- 47,573

- 51

- 3

-

1For some basic information about writing mathematics at this site see, e.g., here, here, here and here. – Another User May 30 '24 at 16:42

-

Welcome to Math.SE! ... Nice problem! :) Express $R$ and $r$ in terms of the triangle's side-lengths in your result relating them, and then see if there's anything that forces those lengths to be in the proportion $1:1:\sqrt{2}$. – Blue May 30 '24 at 16:58

-

1The parameters of these circles are continuous with respect to the points of the triangle, so if there is one such triangle, there are infinitely many of them. – cnikbesku May 30 '24 at 17:17

3 Answers

For an equilateral triangle, the incenter and the outcenter coincide, so clearly the outcenter is inside the inscribed circle. Now include the equilateral triangle in a continuous family of isosceles acute triangles, by keeping one of the sides, say $a$, fixed and increasing the other two sides $b=c$. When $b=c$ is large enough, the outcenter will be outside the inscribed circle, because the outcenter is moving off to infinity whereas the incenter stays within a bounded distance from the side $a$ (say, inside the circle based on $a$ as a diameter). By continuity, there will be an isosceles acute triangle whose outcenter lies on the incircle.

By a similar continuity argument, one can construct many such triangles which are not isosceles, as well. Note that for any obtuse triangle, the outcenter is outside the triangle, whereas the entire incircle is (always) inside the triangle. Hence for an obtuse triangle, the outcenter is outside the incircle. Now connect it to an equilateral triangle by a family avoiding isosceles triangles. By continuity, there must be an intermediate triangle whose outcenter lies on the incircle.

A more general result is due to Chapple: when two circles are the incircle and circumcircle of a triangle, then there is an infinite family of triangles for which they are the incircle and circumcircle. This is the triangular case of Poncelet's closure theorem.

- 47,573

As OP deduced, for the circumcenter to lie on the incircle, we must have $$\frac{\text{inradius}}{\text{circumradius}} = \sqrt{2}-1$$

We know the isosceles right triangle fits this description, so its circumcircle and incircle satisfy the premise of Chapple's Theorem (as noted in @Mikhail's answer). Therefore, they are the circumcircle and incircle of a complete infinite family of triangles, and these are precisely the triangles OP seeks.

By the way, as noted in an ancient answer of mine to what amounts to a duplicate question, these triangles can be characterized by any of these relations:

$$\begin{align} \sin\frac{A}{2}\,\sin\frac{B}{2}\,\sin\frac{C}{2} &\;=\; \frac14\left(\sqrt{2}-1\right) \tag1 \\[8pt] \cos A + \cos B + \cos C &\;=\; \sqrt{2} \tag2 \\[8pt] (-a+b+c)(a-b+c)(a+b-c) &\;=\; 2 a b c \left(\;\sqrt{2}-1\;\right) \tag3 \end{align}$$

- 83,939

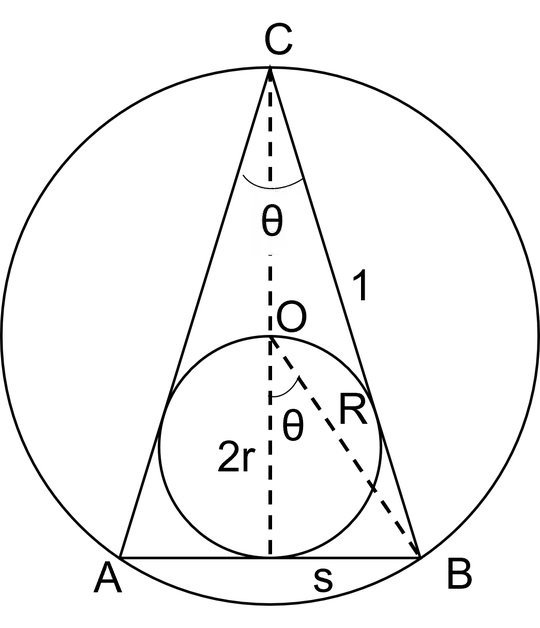

We render the one other isosceles triangle that has its circumcenter lying on the incircle. Instead of lying at the tangency point with the base, this triangle has the circumcenter $O$ at the antipode of this contact point on the incircle:

The legs of the triangle are consideeed the unit length and the apex angle is $\theta$ (labeled with the Roman oetters th due to limitations in my device software). The inradius and circumradius are respectively lowercase $r$ and uppercase $R$, and the base is $2s$ where $s=\sin(\theta/2)$.

Then have the central angle shown also measures $\theta$ and we have from SOH CAH TOA:

$s)2r/R=\cos\theta\implies (2r/R)^2=1-2s^2\tag{1}$

From isosceles $\triangle ACO$ we have

$R=\sec(\theta/2)/2\implies 4R^2=1/(1-s^2)\tag{2}$

and from a standard formula for the inradius:

$r^2=s^2(1-s)/(1+s)\tag{3}$

Using 2 and [3] to eliminate $R$ and $r$ turns 2 into a rational equation of $s$, which is then simplified to give a quartic polynomial equation:

$12s^4-32s^3+20s^2-1=(2s^2-4s+1)(6s^2-4s-1)=0\tag{4}$

Since $\theta$ must be acute, $s/(=\sin(\theta/2)$ must lie between $0$ and $\sqrt2/2$; and this admits one root at $s=1-\sqrt{1/2}\approx0.293$. To the nearest second $\theta\approx34°03'45''$.

Since this root is the only one in range for the required construction, this trianglebis the unique isosceles one. The right isosceles triangle has its circumcenter on the base, not antipodal to it.

- 48,208