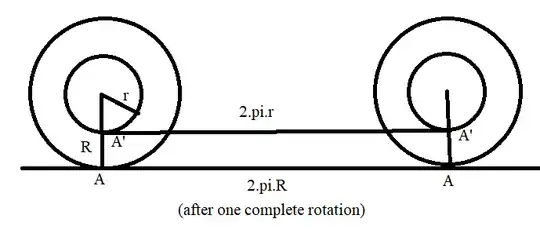

The wheel completes one rotation. By this time the outer circle covers $2\pi R$ distance while the inner circle covers $2\pi r$ distance. And obviously $2\pi R\ne 2\pi r$. But the initial and final position create a rectangle $AA'A'A$ from which we can see $A'A'=AA$ implying that $A$ and $A'$ covered same distance. How is this possible?

Edit: after reading all the suggested links, videos, graphics and valuable comments, I come to know that to cover the distance covered by the outer circle, the inner circle slides or skipps a certain length as its perimeter is smaller than the outer. Galileo first proposed this by experimenting a hexagon and then generalized it taking $n$-gons and then applying $\lim_{n\to 0}$. I have also understood that each point on the perimeters of the two circles has a 1-1 correspondence between them and that's why it seems that both circles cover the same distance. Till now, everything is fair enough to me.

Now my question is if this wheel is a wooden block or made up of something else, in other words, a rigid body, there is no axle or spoke, or it may be just a tyre. An external force is then applied on the tyre just sufficient enough to rotate the tyre once. How the inner surface of the tyre slips? If there is a joint between the outer and inner surface of the tyre, then I perhaps can think the inner surface is slipping w.r.t the outer surface. But the whole tyre is intact. How the inner surface slips while the outer surface just rotates?