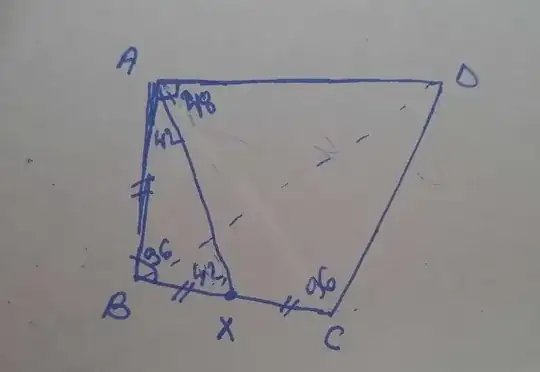

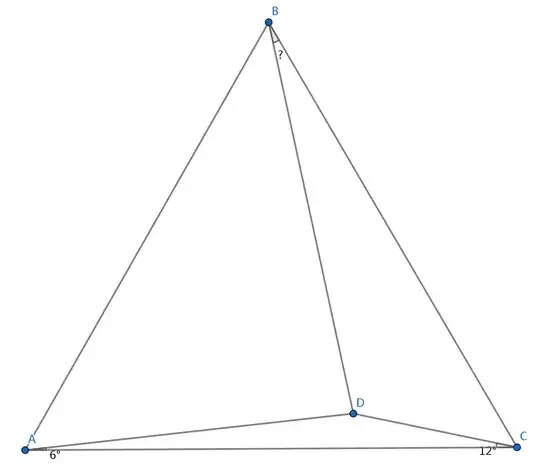

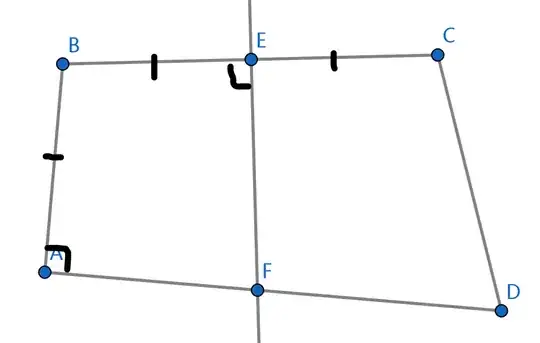

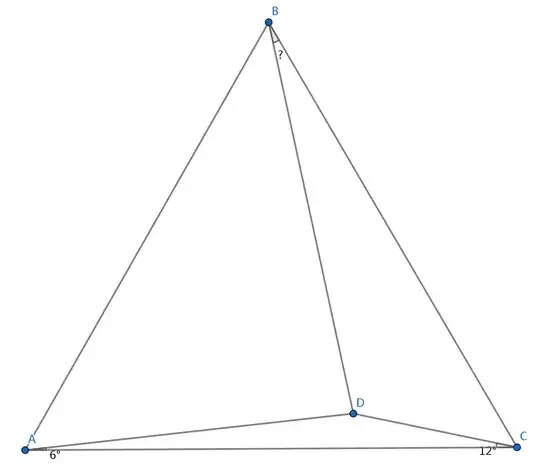

Notice that $BC=2AB$, $\angle A=90^\circ$, let's find the perpendicular bisector of $BC$.

Now we have that $B$ and $C$ are symmetric w.r.t $EF$, and $A$ and $E$ are symmetric w.r.t $BF$. If we extend $AB$ and $DC$, they will intersect $FE$ at the same point, and both make a $6^\circ$ angle. If we extend $CB$ and $DA$, they will make a $6^\circ$ angle as well.

Now we have that $B$ and $C$ are symmetric w.r.t $EF$, and $A$ and $E$ are symmetric w.r.t $BF$. If we extend $AB$ and $DC$, they will intersect $FE$ at the same point, and both make a $6^\circ$ angle. If we extend $CB$ and $DA$, they will make a $6^\circ$ angle as well.

The angle can be found by trigonometry straightforwardly. Let $AB$, $FE$, $DC$ intersect at $Q$. Let $\tan\theta=\tan\angle ABD=\frac{AD}{AB}$.

We have $\frac{AD}{AQ}=\tan 12^\circ$, $\frac{AQ}{AB}=1+\frac{BQ}{AB}=1+\frac{BQ}{BE}=1+\frac{1}{\sin 6^\circ}$. Solve for $\theta$,

$\tan \theta=\frac{AD}{AB}=\tan 12^\circ(1+\frac{1}{\sin 6^\circ})$

$\theta=66^\circ$.

This is probably the best way to find the angle. But the proof can avoid using trigonometry, as the following.

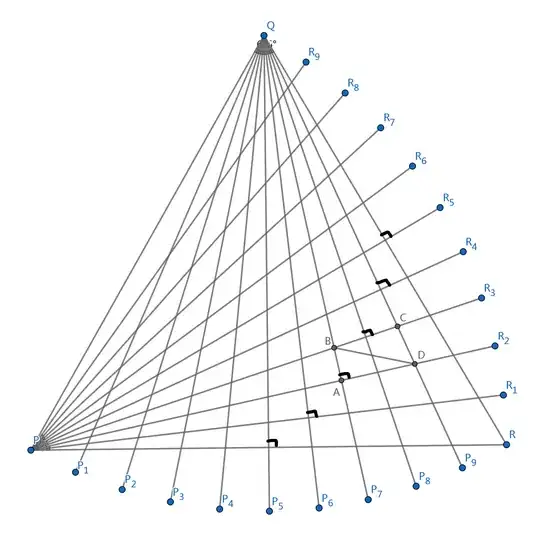

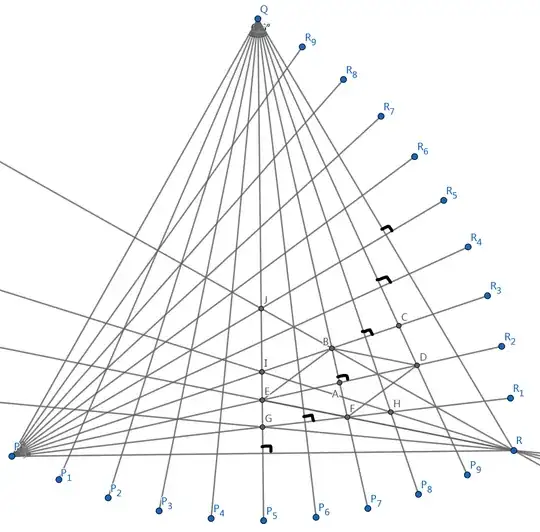

What if we extend all these lines... and draw more to complete an equilateral triangle?

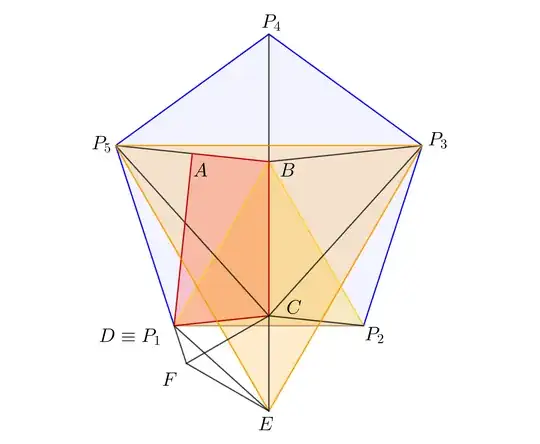

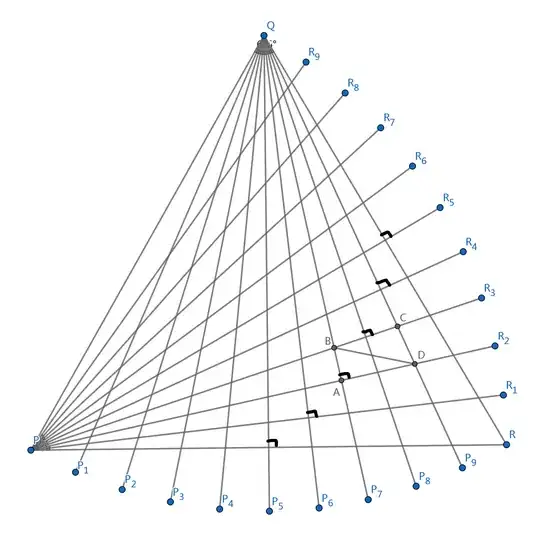

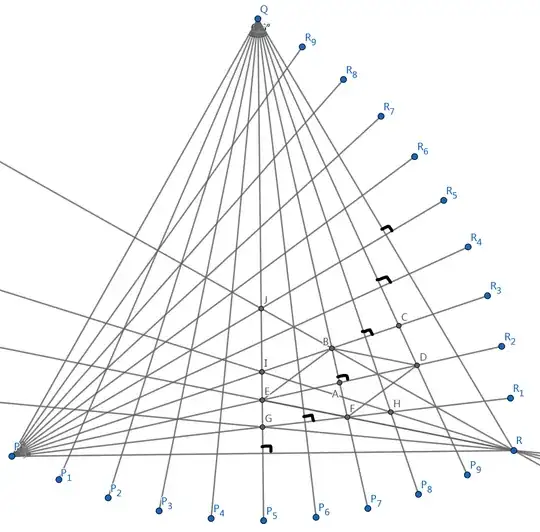

We have an equilateral triangle $\triangle PQR$, and all the $60^\circ$ angles are cut into $6^\circ$ pieces. The location of the quadrilateral $ABCD$ is shown on the graph.

We have an equilateral triangle $\triangle PQR$, and all the $60^\circ$ angles are cut into $6^\circ$ pieces. The location of the quadrilateral $ABCD$ is shown on the graph.

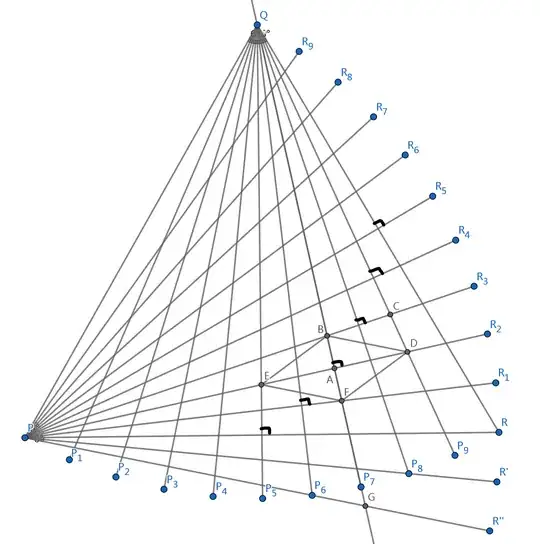

To find $\angle ABD$, we can use symmetry to move it to a different location:

Due to symmetry w.r.t $QP_7$ and symmetry w.r.t $PR_2$, $BD=BE=EF=FD$. So, $\angle ABD=\angle AFE$.

Due to symmetry w.r.t $QP_7$ and symmetry w.r.t $PR_2$, $BD=BE=EF=FD$. So, $\angle ABD=\angle AFE$.

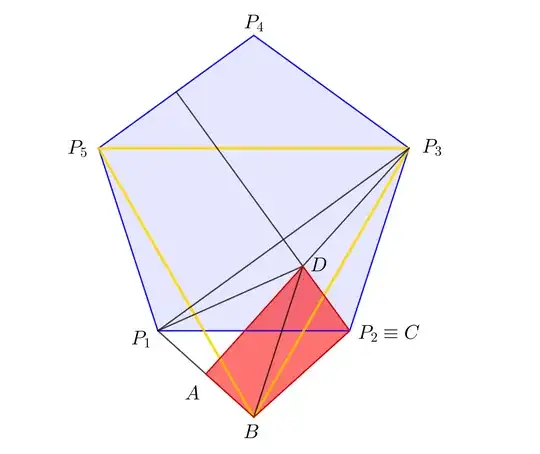

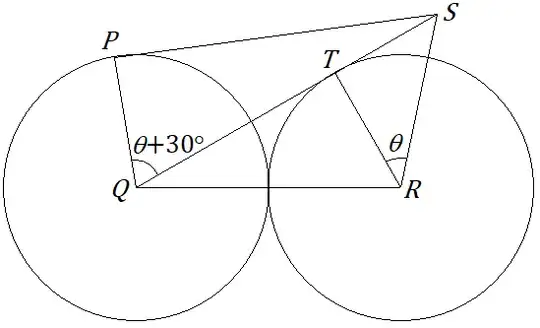

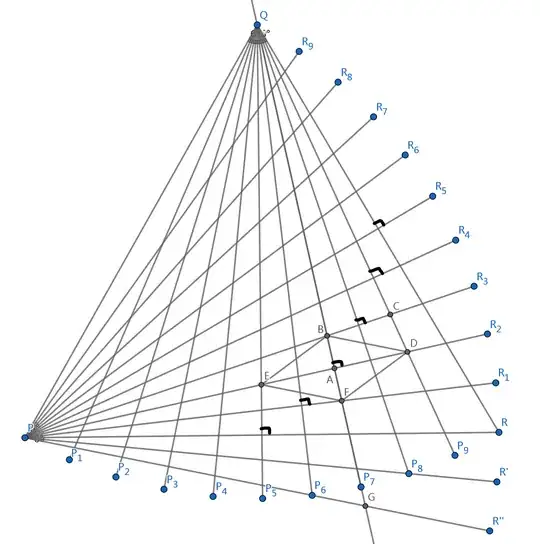

We want to prove that $\angle AFE=66^\circ$, or, $\angle AEF=24^\circ$. Is there a line that makes a $24^\circ$ angle with $AE$?

Yes, if we just add two more lines, $PR'$ and $PR''$, we have that $\angle APR''=4\times 6^\circ=24^\circ$, so we just need to prove that $EF\parallel PR''$.

If we try $\frac{AE}{AP}=\frac{AF}{AG}$, then this can be converted to a tangent identity. $\frac{AE}{AP}=\frac{AE}{AQ}\frac{AQ}{AP}=\frac{\tan 12^\circ}{\tan 42^\circ}$, $\frac{AF}{AG}=\frac{AF}{AP}\frac{AP}{AG}=\frac{\tan 6^\circ}{\tan 24^\circ}$. Thus we must have $\frac{\tan 12^\circ}{\tan 42^\circ}=\frac{\tan 6^\circ}{\tan 24^\circ}$, or

$\tan 12^\circ \tan 24^\circ \tan 48^\circ \tan 84^\circ = 1$,

This is one of the 15 independent four element integer degree tangent identities, which I spent some time trying to understand before.

It's pretty cool to see the connection here, but I'm not going to discuss it any further. Let's go back to the geometry proof.

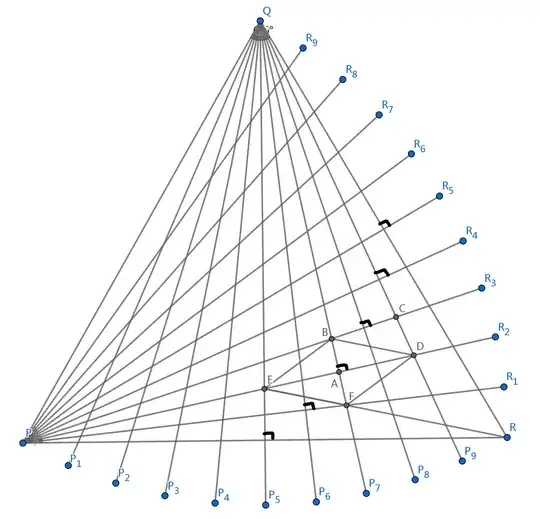

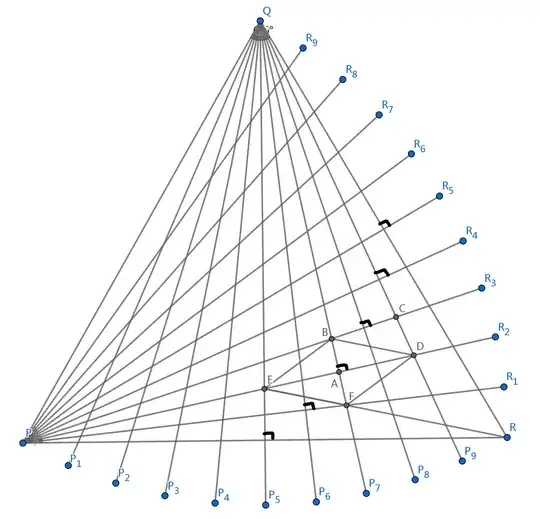

Is there another way to get a $24^\circ$?

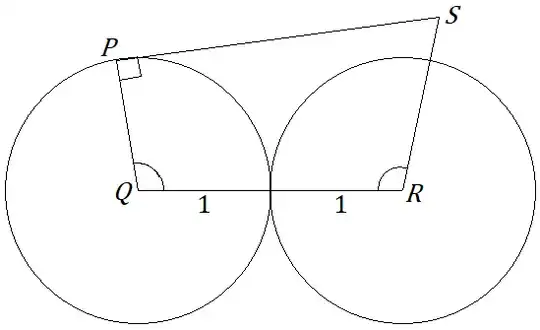

Noticing that $\angle APR=12^\circ$, and $P$ and $R$ are symmetric w.r.t $QE$, so $\angle ERP=12^\circ$ as well. Now, if $F$ is on line $ER$, then it's done, $\angle AEF=24^\circ$!

But how do we prove that $E,F,R$ are on the same line?

Now we can convert it to another problem, a classic:

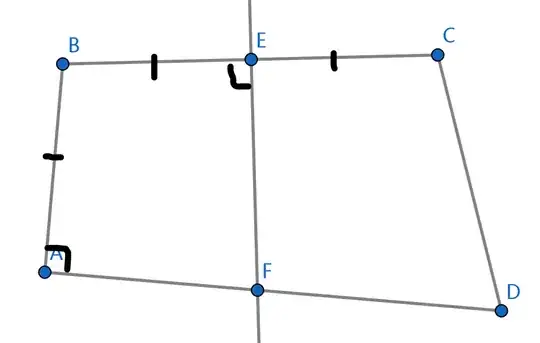

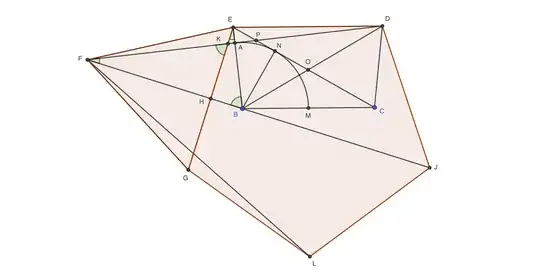

Given equilateral triangle $ABC$, $D$ is inside the triangle, $\angle DAC=6^\circ$, $\angle DCA=12^\circ$. Prove that $\angle CBD=18^\circ$.

There are a few other equivalent formularizations, and there are many solutions. One of them goes as the following:

Find the point $E$ such that $\angle EAD=\angle EDA=6^\circ$. So $EA=ED$.

$ED\parallel AC$, so $AE=CD$.

Find point $F$ and $G$ so that $EF=EA, DG=DC$.

So, $\angle AFE=\angle FAE=48^\circ$, $\angle FED= 2\times 48^\circ+2\times 6^\circ=108^\circ$, $\angle EFD=\angle EDF=36^\circ$. $\angle DGC=\angle DCG=48^\circ$.

$AF=CG$, so $BF=BG$, $BFG$ is equilateral. $FG\parallel DE$, so $\angle GFD=\angle FDE=36^\circ$. $\angle FGD=180^\circ-60^\circ-48^\circ=72^\circ$. So, $\angle FDG=180^\circ-36^\circ-72^\circ=72^\circ=\angle FGD$, $FD=FG$.

So, $FD=FB$, $\angle FBD=\frac{1}{2}\angle AFD=\frac{1}{2}(48^\circ+36^\circ)=42^\circ$, $\angle CBD=18^\circ$. The proof is complete.

One extra fact:

54,6,12,48,18,42 is not the only non-trivial combination that fits in an equilateral triangle. Another one is 54,6,18,42,12,48. And, no, this is not a duplicated combination. Changing the order gives a different problem, and there're quite a few solutions for this problem, too.

On the triangle figure, it implies that, the point $H$ lies on the line $RI$. Quite intriguing facts!

On the triangle figure, it implies that, the point $H$ lies on the line $RI$. Quite intriguing facts!