Suppose we already have the following result:

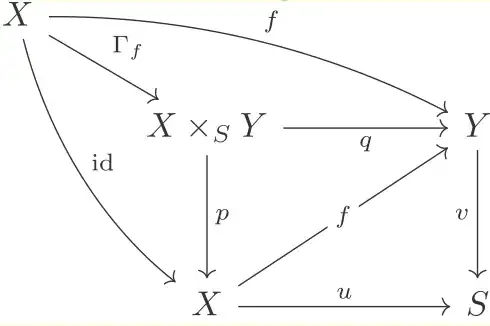

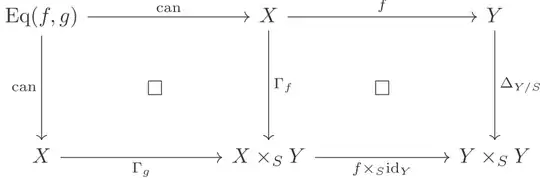

Given any sets $X, Y, S$ and maps $u : X \rightarrow S, v: Y \rightarrow S$ between them, and $S$-maps $f, g: X \rightarrow Y$, i.e., $u = v \circ f = v \circ g$. Then the following diagram is cartesian (i.e., pullback diagram):

\begin{equation*}

\begin{CD}

\operatorname{Eq}(f, g) @>{\operatorname{can}}>> X\\

@V\operatorname{can} V V @VV\Gamma_f V\\

X @>>\Gamma_g> X \times_S Y

\end{CD}

\end{equation*}

We want to show that (just replace the words sets/maps to objects/morphisms):

Given any objects $X, Y, S$ in a category $\mathscr{C}$ and morphisms $u : X \rightarrow S, v: Y \rightarrow S$ between them, and $S$-morphisms $f, g: X \rightarrow Y$, i.e., $u = v \circ f = v \circ g$. Then the aobve diagram is also cartesian (i.e., pullback diagram).

Given any $A \in \operatorname{Obj}\mathscr{C}$, applying the coyoneda functor $h_A$ (Here we reuse the variable names $f,g$):

\begin{equation*}

\begin{cases}

X \mapsto \operatorname{Hom}(A, X) \\

X \xrightarrow[]{f} Y \mapsto (A \xrightarrow[]{g} X \mapsto f \circ g)

\end{cases}

\end{equation*}

on all the above data, we have sets $h(X), h(Y), h(S)$ and maps $h(u): h(X) \rightarrow h(S), h(v): h(Y) \rightarrow h(S)$, and $h(S)$-maps $h(f), h(g): h(X) \rightarrow h(Y)$ (Here we omit the subscript letter $A$ when there is no confusion). Hence applying the assumption, the following diagram is cartesian:

\begin{equation*}

\begin{CD}

\operatorname{Eq}(h(f), h(g)) @>{\operatorname{can}}>> h(X)\\

@V\operatorname{can} V V @VV\Gamma_{h(f)} V\\

h(X) @>>\Gamma_{h(g)}> h(X) \times_{h(S)} h(Y)

\end{CD}

\end{equation*}

Now we should manuplate the above diagram "to commute the limit operations and (co)yoneda applications" (That's why I think it's kind of fuzzy for the general result and it must be handled case by case. Although generally it's from the fact that the yoneda functor preserves limit, but different diagrams seem given different proof here. And it seems hard to make a general statement.) Namely, we want the following diagram that can conclude the statement we want (from the fact that the yoneda functor reflects limit):

\begin{equation*}

\begin{CD}

h(\operatorname{Eq}(f, g)) @>{h(\operatorname{can})}>> h(X)\\

@Vh(\operatorname{can}) V V @VV h(\Gamma_f) V\\

h(X) @>>h(\Gamma_g)> h(X \times_S Y)

\end{CD}

\end{equation*}

From the construction of limits in the category of sets, $\operatorname{Eq}(h(f), h(g))$ is isomorphic to

$$

\left\{x \in h(X) : f \circ x = g \circ x \right\}

$$

But it's isomorphic to the set $h(\operatorname{Eq}(f, g))$. Similarlly we have $h(X) \times_{h(S)} h(Y)$ is isomorphic to the set $h(X \times_S Y)$. (Here we use the word "isomorphic" but not "equal" for respecting the fact that limits are only determined up to unique isomorphism and being very detailed.)

Now we have the following diagram (all askew maps are isomorphisms). We a priori still don't know that the four trapezoidal diagrams are commute. Next we prove this, from which the outer square does be commute and cartesian.

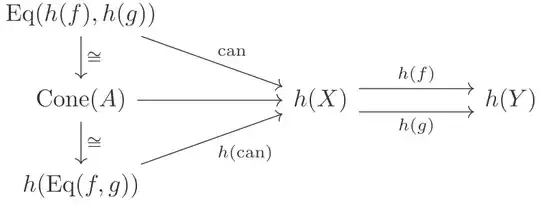

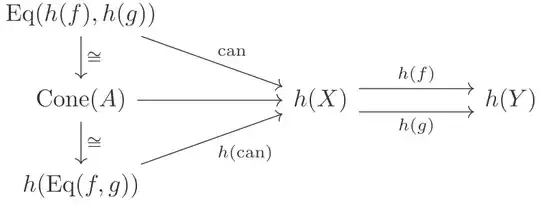

But from the definition for the isomorphism $\operatorname{Eq}(h(f), h(g)) \cong h(\operatorname{Eq}(f, g))$, it's deriven from the following diagram:

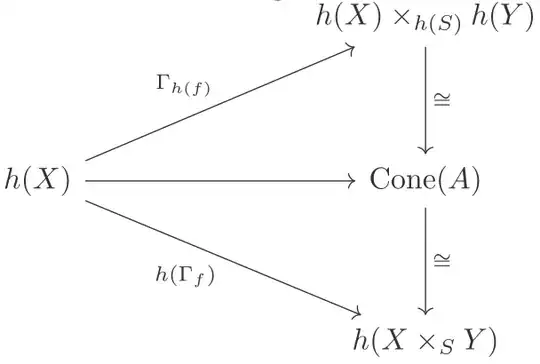

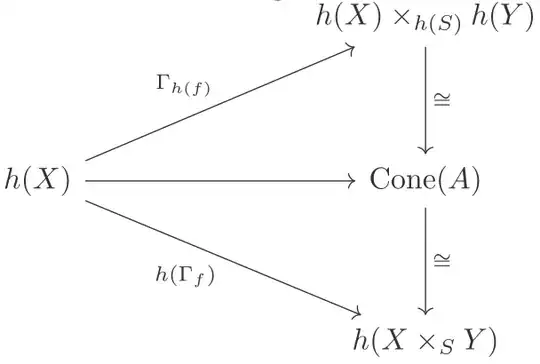

The isomorphism factored from the top triangle diagram is from the fact that limits are unique up to unique isomorphism, and the bottom triangle diagram is commute for its explicit construction: any element (i.e. cone, here just some morphism $x : A \rightarrow X$) is taken to $x$ itself via the morphism $\operatorname{Cone}(A) \rightarrow h(X)$ (the projection), and $\operatorname{Cone}(A) \xrightarrow[]{\cong} h(\operatorname{Eq}(f, g))$ takes $x$ to some $y: A \rightarrow \operatorname{Eq}(f, g)$ in $h(\operatorname{Eq}(f, g))$, and then $h(\operatorname{can}): h(\operatorname{Eq}(f, g)) \rightarrow h(X)$ takes it to $h(\operatorname{can})\circ y$, which is same as $x$. (Here there is some mess up with the notation $\operatorname{can}$: it used for both the canonical morphism for the equalizer $f, g: X \rightarrow Y$ and $h(f), h(g): h(X) \rightarrow h(Y)$). Hence the top trapezoidal does be commute. Similar argument can be applied for others, say the right trapezoidal diagram:

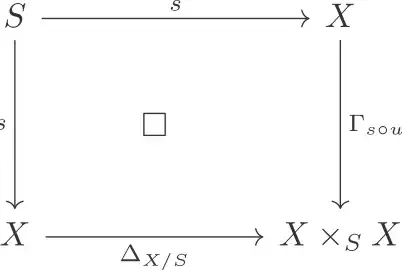

Here $\operatorname{Cone}(A)$ is used for denoting the set of all cones with vertex $A$:

\begin{equation*}

\begin{CD}

A @>>> Y\\

@V V V @VV V\\

X @>>> S

\end{CD}

\end{equation*}

And similarly the top triangle diagram commutes for the uniqueness of limits. And bottom triangle diagram commutes for its explicit construction: any element $x: A \rightarrow X$ in $h(X)$ is taken to the cone $\{x: A \rightarrow X, f \circ x: A \rightarrow Y\}$ by the map $h(X) \rightarrow \operatorname{Cone}(A)$ (recall that $v \circ f = u$):

and then the isomorphism $\operatorname{Cone}(A) \xrightarrow[]{\cong} h(X \times_S Y)$ takes the cone here to some factored morphism $y: A \rightarrow X \times_S Y$. But this is same as $\Gamma_f \circ x$ for the uniqueness of the factored morphism, which is the image of $x$ under $h(\Gamma_f)$.

From the above argument we do have all trapezoidal diagrams commute. And hence the outer square commute. And hence the original diagram in the category $\mathscr{C}$ is commute, for taking $A = \operatorname{Eq}(f, g)$ and checking the identical morphism as FShrike said. And the original diagram is cartesian also following FShrike's answer.

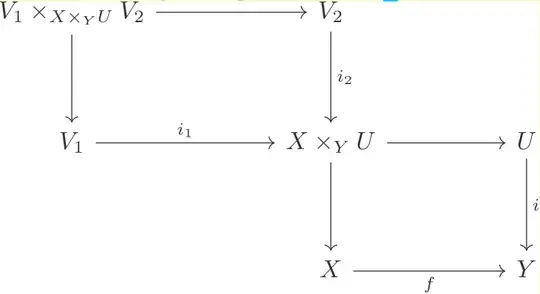

Despite checking the "to commute the limit operations and (co)yoneda applications" for the above specific case, it seems hard to make a general statement about it for the morphisms induced seems different from case to case, say $\operatorname{Eq}(f, g) \xrightarrow[]{\operatorname{can}} X$, or $\Gamma, \Delta$. For example for the third case in the question, it seems quite tedious to check $h(V_1 \times_{X \times_Y U} V_2) \cong h(V_1) \times_{h(X) \times_{h(Y)} h(U)} h(V_2)$ and the related diagrams are commute. Or for example the case shown up in Görtz&Wedhorn that involes a section is hard to include in some general concrete statement but requires specific handles.

Hence the idea here using the yoneda functor maybe treated as some guide line for some concrete proof after some conrete diagram shown up would be better.