Two complex numbers $z,w \in \mathbb C$ determine a triangle with the origin. The (signed) area of this triangle is $$A(z,w)=\frac{1}{2} \det \begin{pmatrix} \Re z & \Re w \newline \Im z & \Im w \end{pmatrix}.$$ You can verify that this is identical to the formula $A(z,w)=\frac 18 (|w+iz|^2-|w-iz|^2)$. This makes me think that there should be some kind of geometric construction that explains this identity, e.g. something like you can take a square in the plane (of some size and orientation), cut out another square, and then find that the leftover area decomposes into 8 identical triangles. I haven't been able to come up with such an argument or construction. And googling for things like "triangle area" or "triangle and difference of squares" only leads to things about high school geometry. Any thoughts?

-

2I find this question very interesting, eventually up to "the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics": is the one you have presented a genuine case of symbolic manipulation with no assignable meaning (geometric in particular, as that seems to be the relevant intuition)? -- For a possible line of attack: just looking at the two formulae (where the essential algebraic difference is that the former is in terms of the components of the input), I can guess a geometric meaning for each, but is there a common geometry that they might be seen as belonging to? – May 08 '24 at 11:41

-

If $|w| = |z|$, then $w + iz$ and $w-iz$ are perpendicular; calculate $\langle w + iz, w - iz \rangle = \mathrm{Re}((w + iz) (\overline{w - iz}))$. So in this case one of the two squares having $w + iz$ as a side contains one of the two squares having $w - iz$ as a side. The smaller square is aligned with the bigger square (parallel sides) and sits flush with one of its corners. Perhaps in this situation there is an insightful way of chopping up $8$ copies of the triangle determined by $z$ and $w$ and arranging these into the difference of squares? – Geoffrey Sangston May 10 '24 at 16:20

-

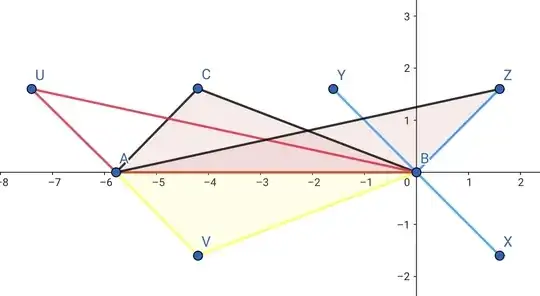

From playing with Geogebra: In the case $|w| = |z|$, $|w + iz| - |w-iz|$ (the difference of the side lengths of the squares) equals $\sqrt{2}$ times $|w - z|$ (the base of the triangle determined by $w$ and $z$), and $|w + iz| + |w - iz|$ equals $2 \sqrt{2}$ times the height of the triangle determined by $w$ and $z$, with respect to the base described. So there could be a nice way of relating the triangle to the rectangle with side lengths $|w + iz| + |w - iz|$ and $|w + iz| - |w-iz|$. See this picture – Geoffrey Sangston May 10 '24 at 16:50

-

1The sequence of steps you do to algebraically prove the identity should encode a natural geometric construction. I intend to write this up when I have time. As an example of this, you can see how the proof of the Pythagorean theorem conveyed by this beautiful animation says $ \langle x, x \rangle + \langle -y, -y\rangle = \langle x, x-y \rangle + \langle -y, x-y\rangle = \langle x - y, x-y \rangle$. – Geoffrey Sangston May 12 '24 at 14:58

5 Answers

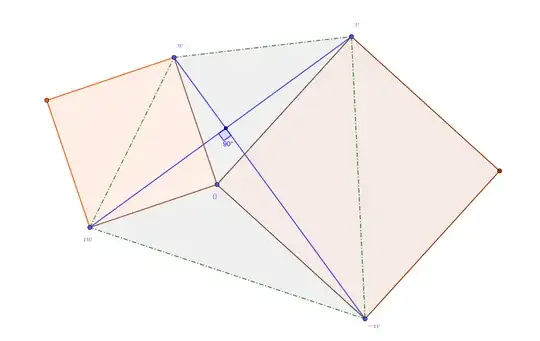

This Geogebra applet ( ) I made shows how to tile $[-B, B]^2 \backslash (-A, A)^2$, $B > A$, by $8$ congruent right triangles. And it's clear how to go from an arbitrary right triangle to a tiling of some $[-B, B]^2 \backslash (-A, A)^2$, $B > A$. By rotating the inside square by a specific amount, you can get a different tiling of a square-minus-square by congruent right triangles. More specifically, this is obtained by starting with a right triangle, reflecting the right-angle across the hypotenuse to obtain a kite, and then using four copies of this kite to produce the tiling of the square-minus-square. Here is a Geogebra applet (

) I made shows how to tile $[-B, B]^2 \backslash (-A, A)^2$, $B > A$, by $8$ congruent right triangles. And it's clear how to go from an arbitrary right triangle to a tiling of some $[-B, B]^2 \backslash (-A, A)^2$, $B > A$. By rotating the inside square by a specific amount, you can get a different tiling of a square-minus-square by congruent right triangles. More specifically, this is obtained by starting with a right triangle, reflecting the right-angle across the hypotenuse to obtain a kite, and then using four copies of this kite to produce the tiling of the square-minus-square. Here is a Geogebra applet ( ) which shows this. The resulting algebraic identity from either construction is $(b + h)^2 - (b-h)^2 = 8 \cdot \frac{1}{2} bh$, where $b$ and $h$ are the lengths of the non-hypotenuse sides of the triangle. This exactly agrees with your version of the polarization identity when $z$ and $w$ are perpendicular.

) which shows this. The resulting algebraic identity from either construction is $(b + h)^2 - (b-h)^2 = 8 \cdot \frac{1}{2} bh$, where $b$ and $h$ are the lengths of the non-hypotenuse sides of the triangle. This exactly agrees with your version of the polarization identity when $z$ and $w$ are perpendicular.

You can do a similar construction for an arbitrary triangle by choosing one of its sides to be the base of a box and its height to be the height of the box. This splits a rectangle into two equal parts, and then you can tile the square-minus-square by four of these rectangles in the same way as before. However, the resulting identity $(b + h)^2 - (b - h)^2 = 8 \cdot \frac{1}{2} bh$ doesn't generally correspond to your polarization identity with respect to the vectors that determine the triangle.

Another way of viewing this last point is the following. Start with an arbitrary triangle. Note that a shear map is area preserving; this can be explained geometrically or algebraically. Shear map the triangle into a right triangle and compose it into either of the two constructions visualized above with Geogebra applets. This shows that the original triangle is one-eighth of the difference of squares. If you apply the inverse shear map to the first construction you'll get Daniel Schepler's construction.

- 2,310

-

2If you take an arbitrary triangle, you could combine two of them to make a parallelogram, and then combine four such parallelograms in a similar way, to at least get the eight triangles as a difference of two rhombuses. Not sure if that might be useful or not for the original question, though. – Daniel Schepler May 08 '24 at 23:31

-

I read the question as asking if given a triangle determined by $w$ and $z$, $8$ copies of it can be used to tile some square-minus-square (with possibly arbitrary orientation) such that the outer square has area $|w + iz|^2$ and the inner square has area $|w - iz|^2$. I predict the best answer to this question is that this is impossible, except for the right triangle (I'd love to be wrong though). – Geoffrey Sangston May 09 '24 at 19:19

-

1It would probably be in the spirit of the question if the eight triangles could be broken down into parts such that rearranging the parts could give a difference of squares. (So for example, if you divided each triangle into three parts along the segments joining the vertices to the incenter, that would give a way to get right angles. No idea whether there would be any way to get such subparts to fit with each other otherwise, though. Another possibility could be to divide one just along an altitude.) – Daniel Schepler May 09 '24 at 19:27

-

@DanielSchepler Yes, I agree. Though, and you probably intended this, it's worth clarifying that it should not only be a difference of squares, but the specific difference of squares for which the bigger square has area $|w + iz|^2$ and the smaller square has area $|w - iz|^2$. The latter part of my answer has a construction which can be viewed as breaking an arbitrary triangle into parts, copies of which arrange into some difference of squares. – Geoffrey Sangston May 09 '24 at 19:33

-

I'm not sure if the question which allows the triangles to be cut up into arbitrary pieces is going to be very interesting however, because of the Wallace–Bolyai–Gerwien theorem. I am not very familiar with this, but I think this means you can divide the square-minus-square into eighths in any way and then apply this theorem to dissect those pieces into sub-pieces which assemble into your triangle. But there may be some insightful way to do it still. – Geoffrey Sangston May 09 '24 at 19:59

-

I'm not sure about your last statement. I don't see how rotating the inside square gives eight congruent right triangles. – Ethan Dlugie May 09 '24 at 20:06

-

@EthanDlugie I edited that part to include a better description and a Geogebra applet. – Geoffrey Sangston May 09 '24 at 20:35

-

2@Daniel Schepler Since the area of a rhombus is just the square of its height, your first comment seems to me to be a perfectly adequate answer to the question, which I'd urge you to write up as an answer. I was about to write up one myself when I realised it was the same as the one you'd given in your comment. I even got as far as constructing an illustrative diagram as a "proof without words", which you'll find here: https://i.sstatic.net/nubdw0rP.jpg. Please feel free to make use of it if you wish. – lonza leggiera May 11 '24 at 11:03

-

@lonzaleggiera leggiera It's not an answer unfortunately, because that difference of squares only agrees with the terms of the polarization identity when the triangles are right triangles. – Geoffrey Sangston May 11 '24 at 13:18

-

1@Geoffrey Sangston Ah yes, I was misled by the briefness of title (not that there's anything wrong with it) into ignoring the identity of the two squares whose difference is being taken. – lonza leggiera May 11 '24 at 13:56

-

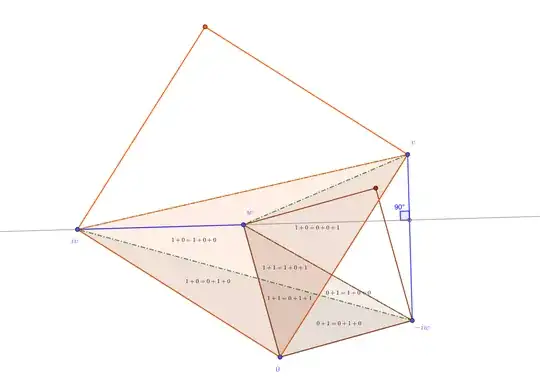

Here's a somewhat involved geometric demonstration of the identity.

The first diagram below is an Argand diagram in which $\ w\ $ (here approximately $\ \frac{{-}33i}{8}\ $) and $\ z\ $ (here approximately $\ \frac{8}{5}(1+i)\ $) are represented by the points $\ A\ $ and $\ Z\ $ respectively. The points $\ Y,$$\,X,$$\,C,$$\,U\ $ and $\ V\ $ represent the points $\ iz,$$\ {-}iz,$$\,w+z,$$\,w+iz\ $ and $\ w-iz\ ,$ respectively. Thus, $\ YBX\ $ and $\ UAV\ $ are parallel straight line segments perpendicular to $\ BZ\ $ and twice its length, $\ AC\ $ is parallel to and the same length as $\ BZ\ ,$ the triangles $\ BAC\ $ and $\ BZA\ $ are congruent, $\ |BU|=|w+iz|\ ,$ and $\ |BV|=|w-iz|\ .$

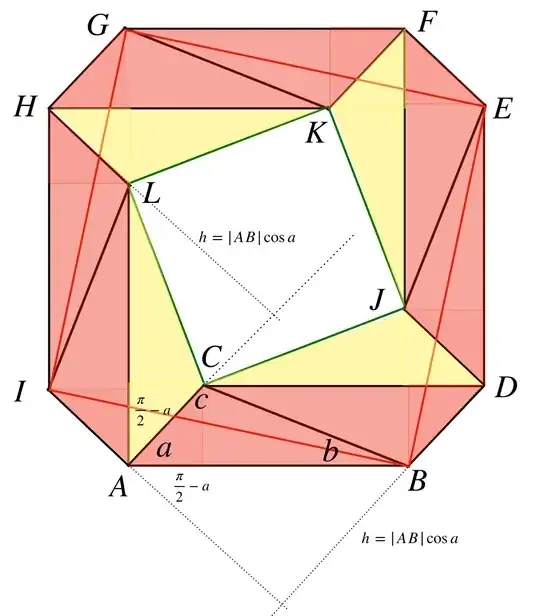

In the second diagram below, the eight red triangles are congruent to the triangles $\ ABC\ $ and $\ BZA\ $ of the Argand diagram, and the angles $\ BAL,$$\,CAI,$$\,IHK,$$\,LHG,$$\,GFJ,$$\,KFE,$$\,EDC\ $ and $\ JDB\ $ are right angles. As a consequence, the four yellow triangles $\ ACL,$$\,HLK,$$\,FKJ\ $ and $\ DJC\ $ are congruent to the triangle $\ ABV\ $ of the Argand diagram, the four triangles $\ IHG,$$\,GFE,$$\,EDB\ $ and $\ BAI\ $ are congruent to the triangle $\ BAU\ $ of the Argand diagram, the green quadrilateral $\ CJKL\ $ is a square with sides of length $\ |w-iz|\ ,$ and the red quadrilateral $\ IGEB\ $ is a square with sides of length $\ |w+iz|\ .$

Now \begin{align} \text{Area of square }\ IGEB=&\text{Area of octagon }\ BAIHGFED\\ &-(4\times\text{Area of triangle }\ BAI)\tag{1}\label{e1} \end{align} and \begin{align} \text{Area of square }\ CJKL=&\text{Area of octagon }\ BAIHGFED\\ &-(4\times\text{Area of triangle }\ ACL)\tag{2}\label{e2}\\ &-(8\times\text{Area of triangle }\ ABC)\ . \end{align} But the area $\ \frac{1}{2}|IA||AB|\cos a\ $ of triangle $\ BAI\ ,$ where $\ a\ $ is the size of the angle $\ BAC\ ,$ is the same as that of triangle $\ ACL\ $—namely $\ \frac{1}{2}|AC||AL|\cos a\ .$ Therefore, subtracting equation (\ref{e2}) from equation $(\ref{e1})$ gives \begin{align} 8\times\text{Area of triangle }\ ABC&=\text{Area of square }\ IGEB\\ &\hspace{2em}-\text{Area of square }\ CJKL\\ &=|w+iz|^2-|w-iz|^2 \end{align}

- 31,984

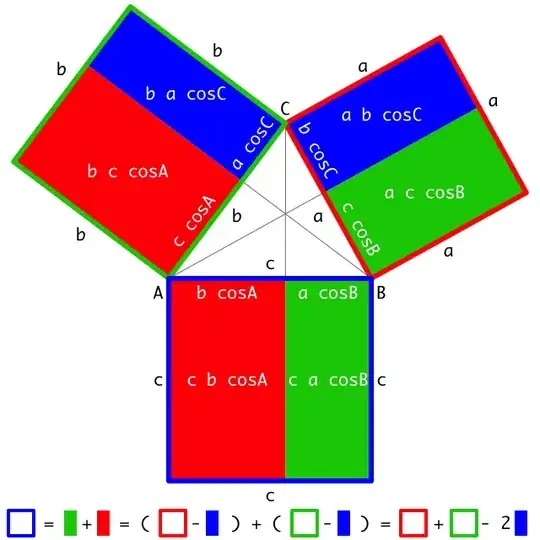

Here's a demonstration that leverages my diagrammatic proof of the Law of Cosines, a version of which is included at the end of this answer.

In detail ...

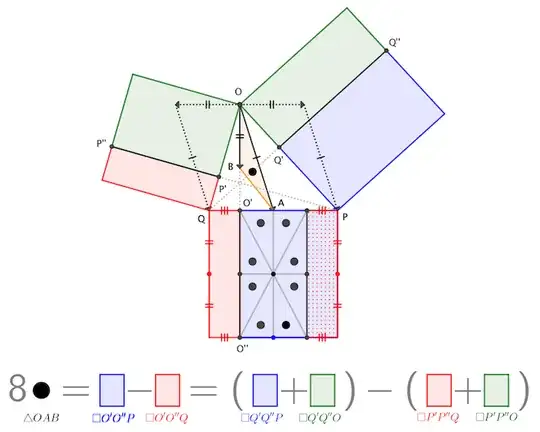

Take $O$ as the origin, and let $\overrightarrow{OA}$ and $\overrightarrow{OB}$ play the roles of complex numbers $w$ and $z$, so that $\overrightarrow{OP}$ and $\overrightarrow{OQ}$ represent $w+iz$ and $w-iz$.

On the sides of $\triangle OPQ$ —which we'll take as non-obtuse for this discussion— erect squares. Importantly, the lower square has side-length $2|OB|$, with $A$ the midpoint of one of the sides, and those sides are parallel and perpendicular to $\overline{OB}$ itself. Finally, drop perpendiculars from the vertices to give segments $O'O''$, $P'P''$, $Q'Q''$ that divide the squares into six rectangles that are pairwise equal in area. (Specifically, "green=green", "red=red", "blue=blue", which is the key observation in the Law of Cosines diagram.)

(BTW: To avoid cluttering the figure with vertex labels, I name each rectangle according to just three of its corners.)

We see that removing a copy of the lower red rectangle $\square O'O''Q$ from the lower blue rectangle $\square O'O''P$ leaves a centered rectangle that clearly sub-divides into eight equal triangles. Each triangle has a "base" (namely, $|OB|$) and corresponding "height" matching those of $\triangle OAB$; hence the areas match, as well. To complete the demonstration of the identity, we simply observe that "blue rectangle, minus red rectangle" is equivalent to "the square on $\overline{OP}$, minus the square on $\overline{OQ}$". $\square$

This approach is a bit less satisfying than, say, a explicit dissection of a difference-of-squares region into eight identical copies of the triangle. Here, except for slicing the central region into eight congruent pieces, the equalities of areas are effectively based on the invariance of area under shearing, which isn't always visually obvious. Nevertheless, the diagram seems to put the elements of the identity into a fairly natural configuration, and makes pretty clear how the factor of $8$ arises.

I should note: The Law of Cosines figure gets a little muddy for obtuse triangles. Everything still works (the Law of Cosines is always valid, after all), but needs to be slightly restated, typically in terms of "signed areas". Likewise, various relative positions of $\overrightarrow{OA}$ and $\overrightarrow{OB}$ complicate the figure above; accommodating those complications is left as an exercise to the reader.

For redundant reference, here's that proof of the Law of Cosines:

- 83,939

This is a good party, let me also join it, a lot of answers with interesting ideas. While trying to get the essence, and possibly simple pictures, i came to the following solution:

First picture:

We start with the grey triangle with vertices in $0,v,w$. Let $S=A(v,w)$ denote its area.

Squares are built on the two sides starting in zero. For each square the diagonal starting in $v$, respectively $w$ is drawn in green. These are two sides of a quadrilateral with perpendicular blue diagonals. Each diagonal has length $|w+iv|$. (Take the absolute value of the difference of the extremities. In the case with the difference $w-(-iv)$ things are clear. In the other case, $v-iw$, multiply with the modulus one complex number $i$.)

We compute the area of the quadrilateral delimited by the green segments in two ways.

- it is the sum of the gray equal areas, together with half areas of the squares.

- it is half the product of the diagonals. (Draw a square with the four vertices on the sides, with sides parallel to the blue diagonals.)

So this picture realized geometrically the identity: $$ S+S + \frac 12|v|^2 +\frac 12|w|^2 = \frac 12|w+iv|^2\color{gray}{=\frac 12|v-iw|^2}\ . $$

Second picture: The above gray part of the formula gives us a hint on how to obtain geometrically also the needed $\displaystyle \frac 12|w-iv|^2$ - we "only" need to exchange the places of $v$ and $w$. Doing so, we must recognize first where is the asymmetry in the above picture. It comes from building the orange square using an $i$-rotation ($+90^\circ$-rotation) of $w$, and a $-i$-rotation ($-90^\circ$-rotation) of $v$, so that the squares are drawn in the exterior of the triangle $(0,v,w)$. So let us draw the same picture "the other way around", the two squares will then point to the interior!

Also note that the signed area $S$ changes into $-S$, the orientation is changed.

In geogebra this is quickly done, we just destroy the above figure exchanging the places of the points $v,w$, and changing the labels to fit with the new positions. But why do we have the "same" formula in the new situation: $$ -S-S + \frac 12|w|^2 +\frac 12|v|^2 = \frac 12|w-iv|\ . $$ Working with negative areas is tricky, so let us work only with positive areas. We want to "see" the equivalent equality: $$ \frac 12|w|^2 +\frac 12|v|^2 = \frac 12|w-iv|+S+S\ . $$ In order to have a documented sight, inside each (colored) piece we have a parallel counting for it, corresponding to:

(orange half square) + (brown half square) = (quadrilateral) + (gray $\Delta(0,-iw,iv)$) + (gray $\Delta(0,v,w)$):

The quadrilateral piece is the non-convex area delimited by green segments. Again it is clear, that its area is the half the product of the two blue segments.

By isolating $2S$ from each formula and adding, we obtain: $$ 2S+2S=\frac 12|w+iv|^2-\frac 12|w-iv|^2\ . $$ $\square$

The brave reader may want now to put the two pictures over each other, and use for the first picture for the half squares the colors orange, and brown, for the second picture the colors minus orange and minus brown.

- 37,952

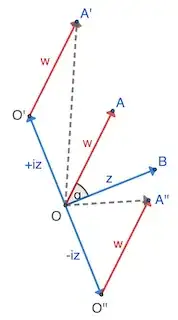

Slightly different from drawing squares, in the above visualization, $OA$ and $OB$ are $w$ and $z$, and $OO'$ and $OO''$ are $iz$ and $-iz$, respectively. Then $OA'$ is $w+iz$ and $OA''$ is $w-iz$. Note that $iz$ is a $90^o$ counter-clockwise rotation of $z$.

Writing the law of cosines for $\triangle{OO'A'}$ and $\triangle{OO''A''}$ we have: $$|OA'|^2 = |w+iz|^2 = |w|^2 + |z|^2 - 2|w||z|\cos(90^o+\alpha)$$ $$|OA''|^2 = |w-iz|^2 = |w|^2 + |z|^2 - 2|w||z|\cos(90^o-\alpha)$$ where $\alpha$ is the angle between $w$ and $z$. Then: $$|w+iz|^2 - |w-iz|^2 = 2|w||z|(\cos(90^o-\alpha)-\cos(90^o+\alpha)) = 4|w||z|\sin\alpha = 8S_{\triangle{OAB}}$$

- 2,548

-

1The Wikipedia page has additional discussion on the equivalence of the law of cosines to the polarization identity. – Geoffrey Sangston May 09 '24 at 16:54

-

-

I wonder if there is a proof along the lines of this picture which effectively uses your diagram in some way. – Geoffrey Sangston May 11 '24 at 14:00

-

@GeoffreySangston It is challenging without the right angle. I tried to get more out of the parallelogram $OAA'O'$, whose diagonals are $|w+iz|$ and $|w-iz|$. Its area is twice $S_{\triangle{OAO'}}$, which is $\frac12|w||z|\cos\alpha$. In comparison, $S_{\triangle{OAB}}=\frac12|w||z|\sin\alpha$. – Saeed May 11 '24 at 18:52