For each $i=1,\dots,13$, let us define $P_i(x,y)$ with $x\neq y\in S:=\{A,B,C,D\}$ as the event of that the card with number $i$ of suit $x$ appear just after the card with number $i$ of suit $y$. Then, the probability of having at least one pair is given by

$$P\left \{(\cup_{i=1}^{13}\cup_{x\neq y\in S}P_i(x,y)) \right\}, $$

which can be computed by the inclusion-exclusion principle considering that the probability of the intersection of any set of events $$P_i(x,y),i=1, \dots,13,x\neq y\in S,$$ can be obtained by counting, but different cases need to be considred. Note that the probability of having a perfect shuffle is

$$1-P\left \{(\cup_{i=1}^{13}\cup_{x\neq y\in S}P_i(x,y)) \right\}. $$

The probability of having exactly one pair in the shuffle (I call it almost perfect shuffle) can be computed using the following extension of the inclusion-exclusion principle:

If $(A_j)_{j\in J}$ is a finite or countable collection of events, then the probability that exactly $k$ of these events occur is

$$p(k)=\sum_i (-1)^{i-k}{i\choose k}\sum \mathbb{P}\left(\bigcap_{j\in J(i)}\, A_j\right)$$

where the sum runs over all subsets $J(i)$ of the index set with $i$ elements.

Now the desired probability is obtained by applying the above to the events $P_i(x,y),i=1, \dots,13,x\neq y\in S$ for $k=1$.

For similar problems, see these old questions 2, 3, and 4.

Remark 1. The calculations are straightforward, but may take a long time. However, the exact formula can be used to calculate the probability with required accuracy. I mean using upper and lower bounds similar to Bonferroni-type inequlities, which require to calculate only a limited number of events.

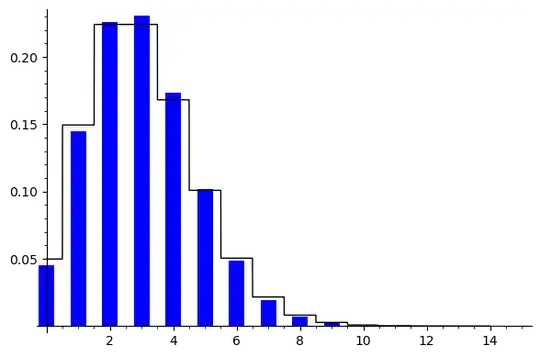

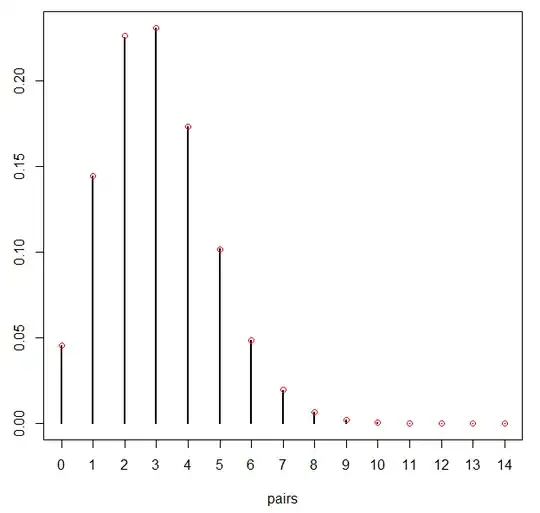

Remark 2. An approximate method to solve such a problem is to use Poisson approximation. We have $n=13×4×3$ events, each occurring with small probability of $p=\frac {1} {52}$, which are approximately independent; hence, the number of events that occur approximately follows Poisson distribution with $\lambda=n×p=3$. Thus, the probability of having

an almost perfect shuffle is about $$P(X=1) \approx \frac{3^1e^{-3}}{1!}=0.149,$$

which is very close to the number $0.145$ obtained from stimulation by @paw88789. Also, it gives $$P(X=0) \approx \frac{3^0e^{-3}}{0!}=0.049,$$ which is very close to the probability of having

a perfect shuffle obtained in 1 as $0.045$.