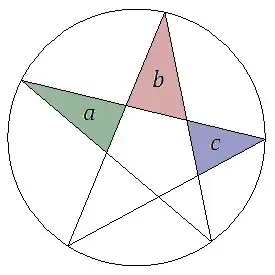

The vertices of a pentagram are five uniformly random points on a circle. The areas of three consecutive triangular "petals" are $a,b,c$. The petals are randomly chosen, but they must be consecutive, either clockwise or anticlockwise.

A simulation of $10^7$ such random pentagrams yielded a proportion of $0.5000179$ satisfying $a^2<bc$.

Is the following conjecture true: $P(a^2<bc)=\frac{1}{2}$

Remarks

Note that the three petals must be consecutive. Calling the areas of consecutive petals $a,b,c,d,e$, simulations suggest that:

- $P(a^2<bd)\approx0.468$

- $P(a^2<be)\approx0.505$

- $P(a^2<cd)\approx0.460$

Curiously, the probability that seems to equal $\frac{1}{2}$, i.e. $P(a^2<bc)$, does not involve a symmetrical arrangement of three petals.

As for other random star polygons $\{\frac{n}{2}\}$ inscribed in a circle, simulations suggest that

- Star polygon $\left\{\frac{6}{2}\right\}$: $P(a^2<bc)\approx0.505$.

- Star polygon $\{\frac{7}{2}\}$: $P(a^2<bc)\approx0.504$.

I used the shoelace formula to calculate the areas of the triangular petals.

One might expect that a probability of $\frac12$ should have an intuitive explanation, but sometimes probabilities of $\frac12$ are hard to explain.

Underlying reason?

Simulations suggest that the random pentagram/pentagon shape is teeming with probabilities of powers of $\frac12$. In the following diagram, the letters represent areas of the regions.

- $P(g+b+h<a+f+c)\overset{?}{=}\color{red}{\frac{1}{2}}$

- $P(g+h<f)\overset{?}{=}\color{red}{\frac{1}{4}}$

- $P((g+a+k)(h+c+i)>(b+f+e+d+j)^2)\overset{?}{=}\color{red}{\frac{1}{8}}$

- $P(\text{each region with area $g,b,f,l$ contains the centre of the circle})=\color{red}{\frac{1}{16}}$ (proved)

- $P(\text{areas of petals increase going around once, clockwise or anticlockwise})\overset{?}{=}\color{red}{\frac{1}{32}}$

I am not asking to prove these other probability claims. I am presenting them to suggest that there may be an underlying reason why the pentagram has probabilities of powers of $\frac12$, which may be relevant to my conjecture. These simulations make me more inclined to believe that my conjecture is true, but I could be wrong.