I asked this question to my calculus teacher and it was a frustrating experience, basically he would say, over and over again, that a tangent line at a point is a line that goes through that point and has a slope equal to the instantaneous slope of the curve at that point. I understand that, I really do, but that is not what I was asking. This all started because, geometrically, a tangent touches the circle once vs a secant touches the circle twice. This of course is no longer the case with any random curve, so I was wondering what is the difference geometrically between a secant line and a tangent line, given that they both can touch the curve multiple times. After thinking about it for a bit, I came up with one possible geometric definition for tangent of a curve, and I would like for you guys to tell me if this is ok and equivalent to the usual definition with derivatives.

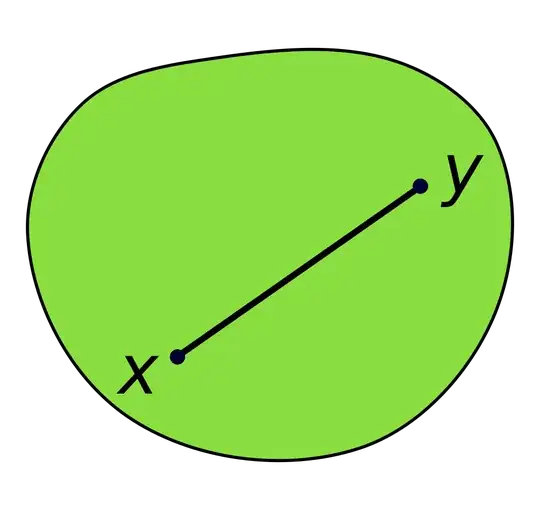

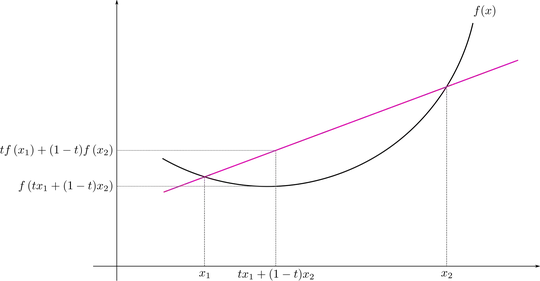

So let $f(x)$ be a curve and $t(x)$ be a line. We say $t(x)$ is a tangent to $f(x)$ at point $x_0$ iff:

- $f(x_0) = t(x_0)$

- $(\exists \delta > 0)(\forall x \in \mathbb{R})(0 < \mid x - x_0 \mid < \delta \implies t(x) > f(x))$ or $(\exists \delta > 0)(\forall x \in \mathbb{R})(0 < \mid x - x_0 \mid < \delta \implies t(x) < f(x))$

In other words, a line is tangent to a curve at a point if it goes through that point and also if you look close enough (for some arbitrarily small $\delta$), all of the points of the line, except for the tangency point, are either on one side of the curve or the other (hence why I wrote two statements one with $t(x) > f(x)$ and another one with $t(x) < f(x)$).

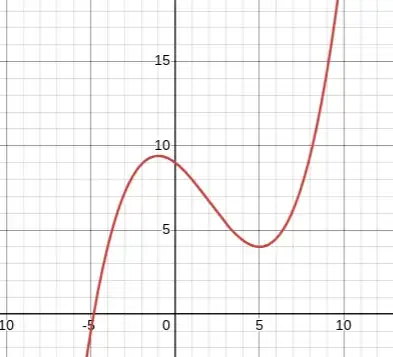

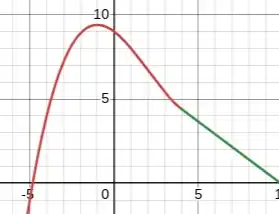

This definition doesn't work for lines, since the tangent of a line is the line itself and this definition wouldn't allow that, but at least for the case of curves, what do you guys think? Can I modify it so that it works for lines too? I am thinking of changing the $<$ and $>$ for $\leq$ and $\geq$ maybe that would make it work for lines. Regardless of whether that definition works or not, it is an example of what I mean when I say "a more geometrical definition of tangent line".