First confidence interval based on sample mean

Considering that $\theta>0$, your confidence interval can be corrected as follows:

$$\color{red}{\small T_1=\max \left( 0,\frac{\overline{X}}{1+\frac{z_{\alpha/2}}{\sqrt{n}}} \right )<\theta<\\T_2=\frac{1}{\max \left( 1-\frac{z_{\alpha/2}}{\sqrt{n}},0 \right ) \max \left( \frac{1}{\overline{X}},0 \right )}},$$

where we adopt the convention that $\frac{1}{0}=\infty$. You should note that the CLT is not required here because for any sample size $n$ we have $$\overline{X}\sim \mathcal N\Big(\theta,\frac{\theta^2}{n}\Big).$$

A better interval is obtained in the following.

Remark: For small $n$, the confidence level of the above interval is greater than $1-\alpha$, that is,

$$\mathbb P \big ( (T_1,T_2)\ni \theta \big) \ge 1-\alpha. $$

Indeed, if $\overline{X}$ or $1-\frac{z_{\alpha/2}}{\sqrt{n}}$ is negative, then $T_2$ becomes $+\infty$, and we cannot retrieve from $(T_1,T_2)\ni \theta $ the first relation:

$$-z_{\alpha/2}\le \sqrt{n} \left ( \frac{\overline{X}}{\theta} -1 \right ) \le z_{\alpha/2}.$$

For negative $\overline{X}$, the resulting interval is $(0, \infty)$. $\overline{X}$ can be negative with probability $1-\Phi(\sqrt{n})$, which is almost $0$ for $n\ge 4$. Thus, for

$$n\ge \max \left (4, z_{\alpha/2}^2\right) $$ the confidence level is $1-\alpha$, i.e., $\mathbb P \big ( (T_1,T_2)\ni \theta \big) = 1-\alpha, $ and we can safely write:

$$T_1=\frac{\overline{X}}{1+\frac{z_{\alpha/2}}{\sqrt{n}}}, T_2=\frac{\overline{X}}{1-\frac{z_{\alpha/2}}{\sqrt{n}}}.$$

Second confidence interval based on sample variance

You can also obtain the following confidence interval:

$$\color{blue}{W_1=\left (\frac{(n-1)S^2}{\chi^2_{n-1,\alpha/2}} \right )^\frac{1}{2}<\theta < W_2=\left (\frac{(n-1)S^2}{\chi^2_{n-1,1-\alpha/2}} \right )^\frac{1}{2}}$$

using the fact that

$$\frac{(n-1)S^2}{\theta^2}\sim \chi^2_{n-1}$$

is a pivotal quantity for $\theta$.

Comparison and discussion

The second interval is better than the first in the sense that it has a smaller expected length, i.e.,

$$\mathbb E(W_2-W_1) \le \mathbb E(T_2-T_1).$$

For small $n$, if $\overline{X}$ or $1-\frac{z_{\alpha/2}}{\sqrt{n}}$ is negative, $T_2$ becomes $+\infty$, and consequently $\mathbb E(T_2-T_1)$ is $\infty$ for small $n$.

For $\alpha=0.05$, if $n\ge 4$, both$\overline{X}$ and $1-\frac{z_{\alpha/2}}{\sqrt{n}}$ are positive, and $\mathbb E(T_2-T_1)$ is finite, given by

$$P(n)=\mathbb E(T_2-T_1) = \underbrace{\mathbb E(\overline{X})}_{\theta}\left ( \frac{1}{1-\frac{z_{\alpha/2}}{\sqrt{n}}}-\frac{1}{1+\frac{z_{\alpha/2}}{\sqrt{n}}} \right).$$

We can also show

$$Q(n)=\mathbb E(W_2-W_1)=\underbrace{\mathbb E(S)}_{\frac{\sqrt{2}\Gamma \left ( \frac{n}{2} \right) }{\Gamma \left ( \frac{n-1}{2} \right)} \theta} \sqrt{n-1} \left ( \frac{1}{\chi^2_{n-1,1-\alpha/2}} - \frac{1}{\chi^2_{n-1,\alpha/2}}\right).$$

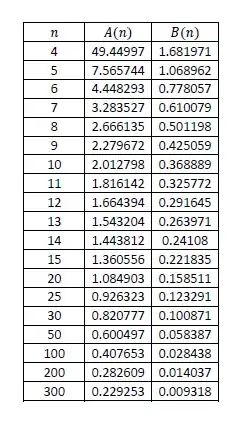

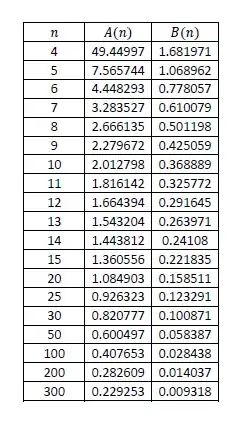

Now we compare $P(n)$ with $Q(n)$. In the following table, you can see values of $A(n)=\frac{P(n)}{\theta}$ and $B(n)=\frac{Q(n)}{\theta}$ for different sample sizes, which shows that the expected length of the second is significantly smaller and it rapidly tends to $0$.

$\hspace{3cm}$

Finally, note that the statistics $\overline{X^2}$ and $\overline{X}$ are minimally sufficient for the distribution $\mathcal N\Big(\theta,\theta^2\Big)$ (see here and here). Hence, we may be able to design better confidence intervals based on some clever combinations of the two statistics $\overline{X^2}$ and $\overline{X}$. In fact, the sample variance $S^2$ can be considered such a combination by noting that

$$S^2=\frac{n}{n-1} \left( \overline{X^2} - \overline{X}^2 \right).$$

The above analysis shows that only using $\overline{X}$ yields a weak interval, which is not the case when $\sigma^2$ is known since $\overline{X}$ is sufficient for $\mathcal N\Big(\theta,\sigma^2\Big)$ with known $\sigma^2$.