We show that if $\sigma(n)$ is exponential then the series tends towards $1/2$ but retains an oscillation about this value and does not completely converge.

Let $\sigma(n)=3^n$ and sum from $n=0$ to $n=\infty$, thus

$f(x)=\lim_{x\to1^-}\sum\limits_{n=0}^\infty (-1)^n x^{3^n}.$

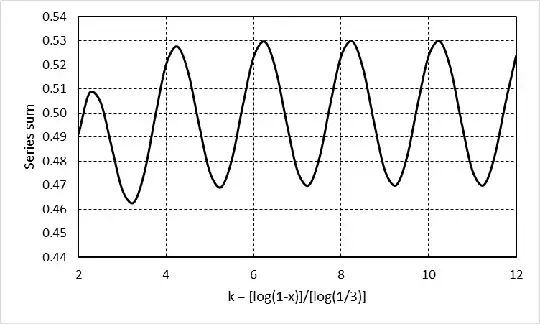

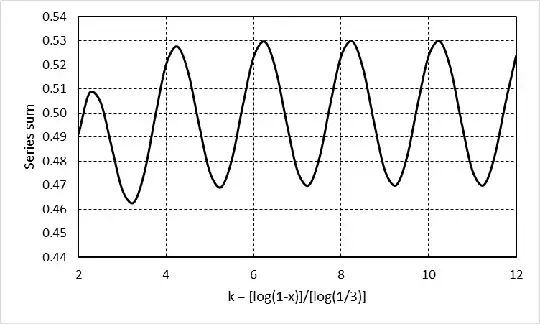

The following graph shows a plot of this function from Microsoft Excel where data were obtained for

$x=1-3^{-k}$

with $k$ from $2$ to $12$ in increments of $1/4$ (we will see shortly why increments as large as $1$ would not work):

One might suppose the sinusoidal variation mught be due to roundoff error, but the operation is not particularly ill-conditioned and the $1-x$ values explored exceed $10^{-6}$ even at the right end of the graph (largest $k$, smallest $1-x$ explored).

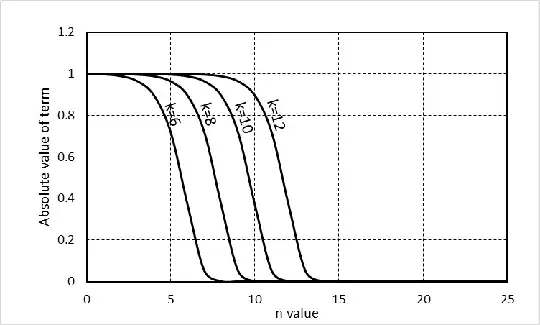

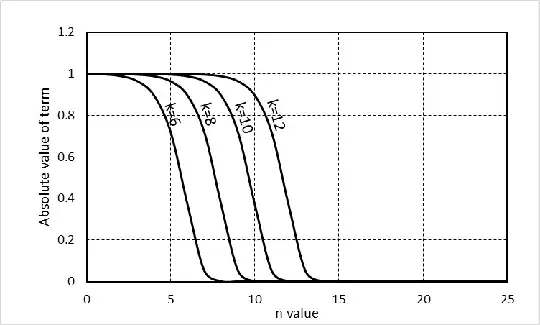

What is really going on? Below is a graph showing how the absolute values of the summation terms decrease with increasing $n$ for various $k$ values.

It becomes evident that the transition from $\pm1$ to $0$ in the terms tends to a constant shape that translates one unit towards increasing $n$ with each increment of one in $k$. This behavior would not be seen with a polynomial function for $\sigma$, for in that case the variation of $\sigma$ with $n$ would be slower and the transition would flatten out instead.

With the constant-shape transition comes a nonzero deviation from the limiting Cesarò sum of $\pm1$ terms, which modifies the $1/2$ that would be obtained from the $\pm1$ terms alone. We just saw that balancing an increment of one unit in $n$ with an equal increment of $k$ one unit preserves the absolute values of the respective terms in this region as $x\to1^-$, but the $n$ increment also changes the signs of the terms. Therefore each unit increment of $k$ will produce an undamped sign change in the curved region's contribution summed over all $n$. This oscillation characteristic matches the observed graph in the first figure above for $k>3, 26/27<x<1$.