Find the possible remainders of $(1-3i)^{2009}$ when divided by $13+2i$ in $\mathbb{Z}[i]$.

I'm having a hard time understanding remainders in $\mathbb{Z}[i]$. I'm gonna write my solution to the problem above just to give some context, but you can skip this part and read the question below if you want. We start by noticing that $N(13+2i) = 173$, which is a prime number. Therefore, $13+2i$ is irreducible in $\mathbb{Z}[i]$. This allows us to quickly calculate the number of elements of the multiplicative group $(\mathbb{Z}[i]/(13+2i))^{\times}$, namely $N(13+2i) - 1 = 172$. By Lagrange's Theorem, since $1-3i$ and $13+2i$ are coprime, $$(1-3i)^{11\cdot 172} \equiv 1\mod(13+2i).$$ We now reduced the problem to finding $(1-3i)^{117} \mod (13+2i)$. Note that $117 = 3^2\cdot 13$, so by a tedious but direct calculation (once we figure out $(1-3i)^{3^2}$ modulo $13+2i$ we get a nice expression, so the $13$th power is relatively straightforward to compute), we arrive at $6-2i$.

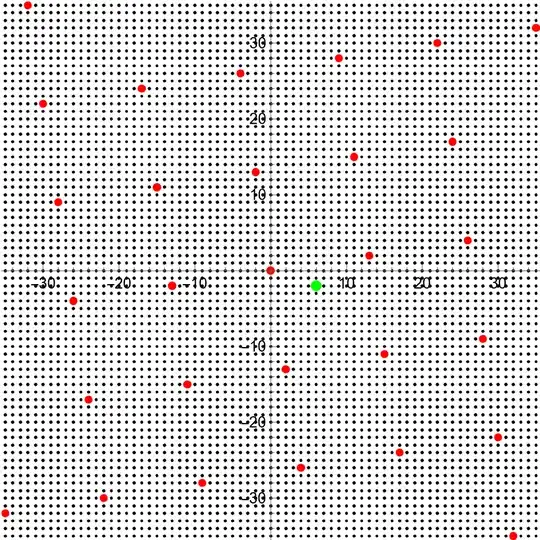

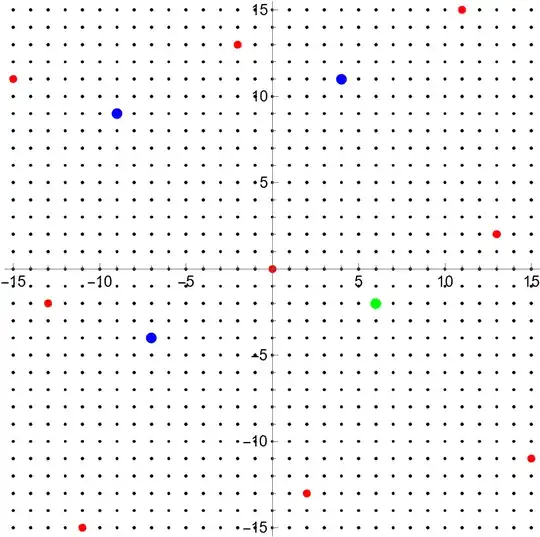

Question: Remainders in $\mathbb{Z}[i]$ are not uniquely determined and, from my understanding, there are $4$ possible choices. It is not difficult to find different remainders when we are working with small numbers and can test various quotients. In this case, however, how would I determine the other possible choices? Are they somehow related? For instance, when I was calculating $(1-3i)^{3} = -26+18i$, I found that $$(1-3i)^{3} = (-2+i)(13+2i) + (2+9i) = (-1+2i)(13+2i) + (-9-6i).$$ The remainders above have norms $N(2+9i) = 85$ and $N(-9-6i) = 117$. I thought they would have to be associates, but the example above shows they are not and, even worse, $\operatorname{gcd}(85, 117) = 1$.