Consider a moving point $V$ on the circumference of the given circle, the total distance is

$ D = AV + BV = \| V - A \| + \| V - B \| \\ = \sqrt{(V(\phi) - A)\cdot(V(\phi) - A)} + \sqrt{(V(\phi)-B)\cdot(V(\phi)-B)} $

where $\phi$ is the central angle of $V$ from a fixed ray originating at the center $C$.

Take the derivative of $d$ with respect to $\phi$, then

$ \dfrac{dD}{d\phi} = V'(\phi) \cdot \left( \dfrac{ (V - A)}{\| V - A \|} + \dfrac{ (V-B)}{\|V-B\|} \right) $

Now $V'(\phi)$ (the $\phi$ derivative of $V$ ) is tangential to the circle. And what this equation means is that the tangent vector at $V$ is perpendicualar to the sum of these two unit vectors. Since this sum is a vector that bisects the angle between them, then we conclude that at the minimum distance $D$, the normal vector to the circle bisects the rays $VA$ and $VB$.

Next, we will find the location of this point $V$.

Let $Y = \angle ACB $, and let $x = \angle ACV$, and let $\alpha = \dfrac{1}{2} \angle AVB $

Applying the law of sines to $\triangle ACV $ and $\triangle BCV$ and noting that $ \angle VAC = \alpha - x $ and $\angle VBC = \alpha - (Y - x) $, we get,

$ \dfrac{ \sin(\alpha - x) }{r} = \dfrac{\sin(\alpha) }{CA} $

and

$ \dfrac{ \sin(\alpha - (Y-x)) }{r} = \dfrac{\sin(\alpha) }{CB} $

After expanding $\sin(\alpha - x)$, we get

$ \tan(\alpha) = \dfrac{ \sin(x) }{\cos(x) - r / CA } $

Similarly from the second equation, we get

$ \tan(\alpha) = \dfrac{ \sin(Y-x) }{\cos(Y-x) - r/ CB} $

Equating the two and cross multiplying gives us

$ \sin(x) (\cos(Y-x) - \dfrac{r}{CB} ) = \sin(Y - x) (\cos(x) - \dfrac{r}{CA} ) $

Expanding $\cos(Y-x)$ and $\sin(Y - x)$ gives

$ \sin(x) ( \cos(Y) \cos(x) + \sin(Y) \sin(x) - \dfrac{r}{CB} ) = (\sin(Y) \cos(x) - \cos(Y) \sin(x) ) (\cos(x) - \dfrac{r}{CA} ) $

Collecting terms,

$ [\dfrac{r}{CA} \sin(Y)] \cos(x) + [-\cos(Y) \dfrac{r}{CA} -\dfrac{r}{CB}] \sin(x) + \sin(Y) ( \sin^2(x) - \cos^2(x) ) + \cos(Y) \sin(2 x) = 0 $

And this reduces further to

$ [\dfrac{r}{CA} \sin(Y) ] \cos(x) + [-\cos(Y) \dfrac{r}{CA} -\dfrac{r}{CB} ] \sin(x) + [ - \sin(Y) ] \cos(2x) + [\cos(Y)] \sin(2x) = 0 $

which is an equation of the form

$ A \cos(x) + B \sin(x) + C \cos(2x) + D \sin(2x) = 0 $

It is not straightforward nor easy to obtain the solution of this equation. The solution is through introducing a change of variable by the substitution $z = \tan\left(\dfrac{x}{2}\right) $. This is a well-known substitution, with which we can express $\cos(x), \sin(x)$ as follows:

$\cos(x) = \dfrac{1 - z^2}{1 + z^2} $

$ \sin(x) = \dfrac{2z}{1 + z^2} $

And using the fact that $\sin(2x) = 2 \sin(x) \cos(x) $ and that $\cos(2x) = 2 \cos^2(x) - 1 $, we substitute this rational expressions in $z$ into the trigonometric equation to obtain a rational function in $z$. Multiplying through by the common denominator gives a numerator which is a degree $4$ polynomial in $z$. The next step is to find the roots of this polynomial, and this is possible using known formulas for the roots of degree $4$ polynomial. But implementing the formulas is not trivial at all. Once the roots are found, the angles can retrieved from the roots by the formula $ \theta = 2 \tan^{-1}(z) $. It is easy to exclude extraneous values of $\theta$ given the expected range which is $[0, Y]$.

That said, it is best to utilize a math app to find the roots of the trigonometric equation above.

Or, you could also, solve numerically using a simple and straightforward method which is the well-celebrated Newton's Method. The method is quite easy to use, and all you need is to determine the derivative of the trigonometric function above.

Numerical Example:

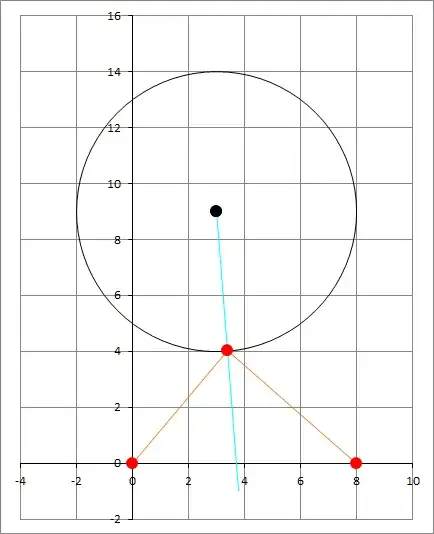

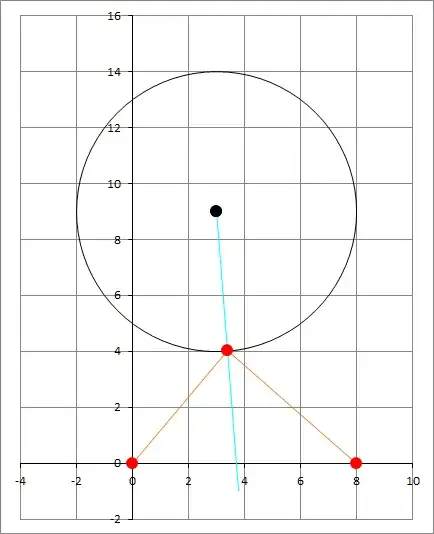

With $C = (3,9), A = (0,0), B = (8,0),r = 5$ and using the above outlined procedure, we get the following figure for the shortest path. The cyan segment shows that the normal to the circle bisects $\angle AVB$.