In Bridges' Foundations of Real and Abstract Analysis, I read about the following theorem.

(5.2.2) Proposition. Let $S$ be a nonempty closed subset of the Euclidean space $\mathbb R^N$ such that each point of $\mathbb R^N$ has a unique closest point in $S$. Then $S$ is convex.

This theorem is proved by contradiction and to invoke the contradiction, the author relies on a previous exercise which I simply can not fathom. If anyone knows what the gist of this is about, and knows how to prove it, I'd be very grateful for some guidance. The exercise reads as follows:

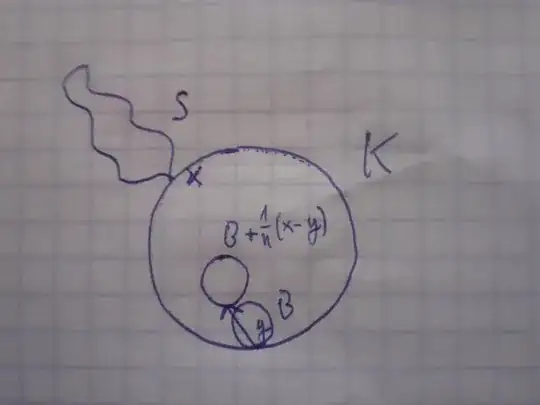

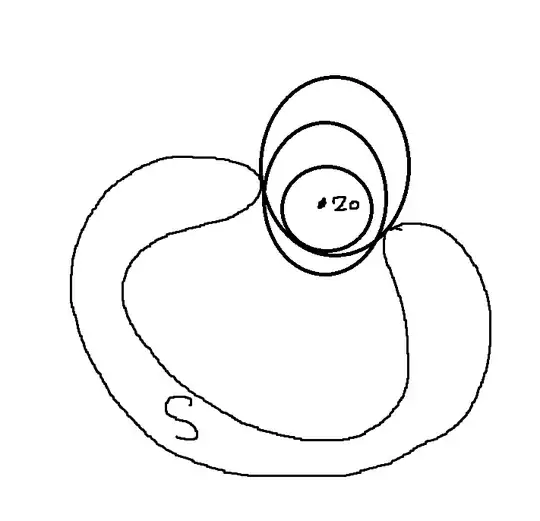

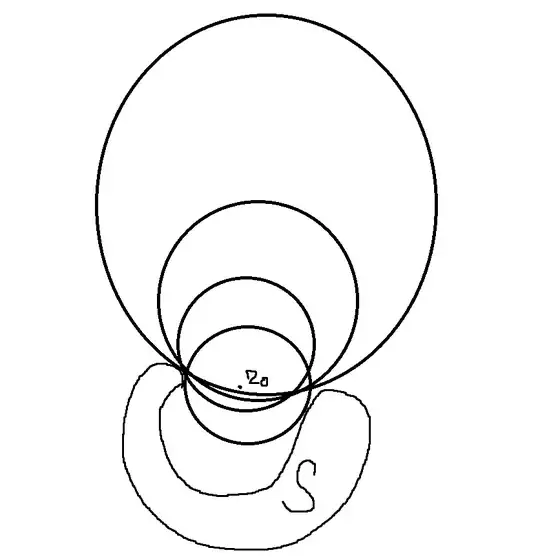

(4.3.7.7) Let $S$ be a nonempty closed subset of $\mathbb R^N$, and $K,B$ closed balls in $\mathbb R^N$ such that (i) $B\subset K$ and (ii) $K$ intersects $S$ in a single point $x$ on the boundary of $K$. If $B$ does not intersect the boundary of $K$, let $y$ be the centre of $B$; otherwise, $B$ must intersect the boundary of $K$ in a single point, which we denote by $y$. For each positive integer $n$ let $$K_n=\frac1{n}(y-x)+K.$$ Prove that for sufficiently large $n$ we have $B\subset K_n$ and $K_n\cap S=\emptyset$. Hence prove that there exists a ball $K'$ that is concentric with $K$, has radius greater than that of $K$, and is disjoint from $S$.

(For the first part, begin by showing that there exists a positive integer $\nu$ such that $B\subset K_n$ for all $n\geq \nu$. Then suppose that for each $n\geq \nu$ there exists $s_n\in K_n\cap S$. Show that there exists a subsequence $(s_{n_k})$ converging to $x$, and hence find $k$ such that $s_{n_k}\in K\cap S$, a contradiction.)

Unfortunately, I haven't been able to find anywhere in the book if $\subset$ is proper inclusion or not. When the author writes $K_n=\frac1{n}(y-x)+K$, I take it to mean the set $K_n=\{\frac1{n}(y-x)+k:k\in K\}$.

I'm somewhat of a beginner to this and the exercise seems very unintuitive to me. If $K$ intersects $S$ at a single point, how can there be a ball, concentric with $K$, and radius greater than $K$, but that is disjoint from $S$?

As for trying to solve this exercise, let's suppose $B$ does not intersect the boundary of $K$, then define $d(z,B)=\inf \{ d(z,b):b\in B \}$. Let $z\in B-\frac{1}{n}(y-x)$, then by the triangle inequality $$d(z, K^c) \geq d\left(z+\frac{1}{n}(y-x), K^c\right) - d\left(z, z+\frac{1}{n}(y-x)\right)$$ The first term on the right is positive, because $z+\frac{1}{n}(y-x)$ is a point in $B$, i.e. in the interior of $K$, and a point belongs to the interior of a set if and only if the distance from the point to the complement is strictly positive. The second term is simply $\frac{1}{n}\lVert y-x\rVert$ and this can be made arbitrarily small. So $d(z, K^c)$ is positive and it follows that $z\in K^\circ \subset K$, so $B-\frac{1}{n}(y-x)\subset K$, i.e. $B\subset K+\frac{1}{n}(y-x)=K_n$.

I'm not sure if this proves the first part, but it remains to prove the case when $B$ does intersect $K$ and moreover, that $K_n\cap S=\emptyset$. The below picture is a sketch of the case when $B$ intersects $K$. The arrow denotes the vector $\frac{1}{n}(x-y)$.

EDIT: Here's the proof of the proposition above, word by word:

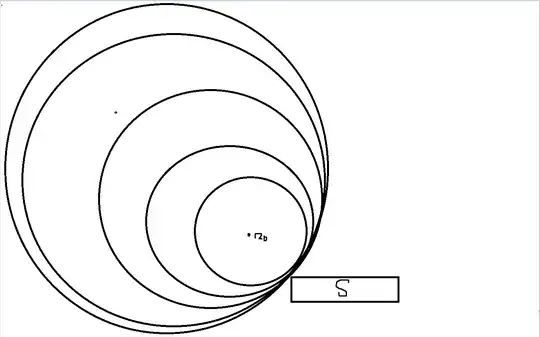

Proof. Supposing that $S$ is not convex, we can find $a,b\in S$ and $\lambda\in (0,1)$ such that $$z=\lambda a+(1-\lambda)b\not\in S.$$ Since $X\setminus S$ is open, there exists $r>0$ such that $\overline{B}(z,r)\cap S=\emptyset$. Let $\mathcal{F}$ be the set of all closed balls $B$ such that $\overline{B}(z,r)\subset B$ and $S\cap B^\circ=\emptyset$; then $\overline{B}(z,r)\in \mathcal{F}$. The radii of the balls belonging to $\mathcal{F}$ are bounded above, since any ball containing $B$ and having sufficiently large radius will meet $S$. Let $r_{\infty}$ be the supremum of the radii of the members of $\mathcal{F}$, and let $(\overline{B}(x_n,r_n))_{n=1}^\infty$ be a sequence of elements of $\mathcal{F}$ such that $r_n\to r_\infty$. Then $x_n\in \overline{B}(z,r_\infty)$ for each $n$. Since $\overline{B}(z,r_\infty)$ is compact (Theorem (4.3.6)) and therefore sequentially compact (Theorem (3.3.9)), we may assume without loss of generality that $(x_n)$ converges to a limit $x_\infty$. Let $K=\overline{B}(x_\infty,r_\infty)$; we prove that $K\in \mathcal{F}$.

First we consider any $x\in \overline{B}(z,r)$ and any $\epsilon>0$. Choosing $m$ such that $\lVert x_m-x_\infty\rVert<\epsilon$, and noting that $\overline{B}(z,r)\subset\overline{B}(x_m,r_m)$, we have \begin{align} \lVert x-x_\infty \rVert&\leq \lVert x-x_m\rVert +\lVert x_m-x_\infty\rVert \\ &<r_m+\epsilon\\ &\leq r_\infty+\epsilon. \end{align} Since $\epsilon$ is arbitrary, we conclude that $\lVert x-x_\infty\rVert\leq r_\infty$; whence $\overline{B}(z,r)\subset K$. On the other hand, supposing that there exists $s\in S\cap B(x_\infty,r_\infty)$, choose $\delta>0$ such that $\lVert s-x_\infty\rVert<r_\infty-\delta$, and then $n$ such that that $0\leq r_\infty-r_n<\delta/2$ and $\lVert x_n-x_\infty\rVert<\delta/2$. We have \begin{align} \lVert s-x_n \rVert&\leq \lVert s-x_\infty\rVert +\lVert x_\infty-x_n\rVert \\ &<r_\infty-\delta+\frac{\delta}{2} \\ &=r_\infty-\frac{\delta}{2} \\ &< r_n, \end{align} so $s\in S\cap B(x_n,r_n)$. This is absurd, as $B(x_n,r_n)\in\mathcal{F}$; hence $S\cap B(x_\infty,r_\infty)$ is empty, and therefore $K\in\mathcal{F}$.

Now, the centre $x_\infty$ of $K$ has a unique closest point $p$ in $S$. This point cannot belong to $K^\circ$, as $K\in\mathcal{F}$; nor can it lie outside $K$, as $r_\infty$ is the supremum of the radii of the balls in $\mathcal{F}$. Therefore $p$ must lie on the boundary of $K$. The unique closest point property of $S$ ensures that the boundary of $K$ intersects $S$ in the single point $p$. It now follows from Exercise (4.3.7:7) that there exists a ball $K'$ that is concentric with $K$, has radius greater than $r_\infty$, and is disjoint from $S$. This ball must contain $\overline{B}(z,r)$ and so belongs to $\mathcal{F}$. Since this contradicts our choice of $r_\infty$, we conclude that $S$ is, in fact, convex.