The series $\sum x_n$ diverges.

First, we may assume $(a_n)$ has all distinct terms. For this, the repeating terms of $(a_n)$ contribute zero toward $\sum x_n$. Let $(a_n)$ be dense in an interval $(a,b)$. We prove that $(x_n)$ constructed by $x_1=0$, $x_n:= \displaystyle\min_{1\leq k < n} \lvert a_n - a_k\rvert$ gives the divergence of $\sum x_n$. Since $a_n=\sin n$ is dense in $(-1,1)$, $\sum x_n$ is divergent.

To see this, assume that $\sum x_n$ converges. Then there is $N\in\mathbb{N}$ such that $\sum_{n>N} x_n < (b-a)/2$.

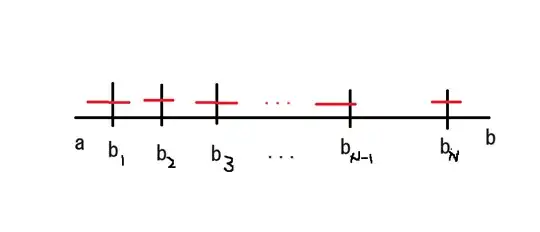

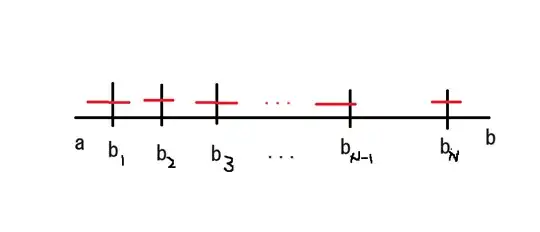

Let $b_1<\cdots <b_N$ be the numbers $a_1,\ldots, a_N$ in an increasing order. For $a_{N+1}$, it is closest to some number $a_1, \ldots, a_N$. Find the smallest index $k\leq N$ such that $a_{N+1}$ is closest to $a_k$. Then color red over the interval $[\min(a_{N+1},a_k),\max(a_{N+1},a_k)]$. The red interval has the length $x_{N+1}$. We repeat the procedure. Given $a_1,\ldots, a_{N+j}$, Find the smallest index $m\leq N+j$ such that $a_m$ is closest to $a_{N+j+1}$. Then color red over $[\min(a_{N+j+1},a_m),\max(a_{N+j+1},a_m)]$.

In this procedure, the new red interval is either contained in the already existing red interval or extends the already existing red interval. Repeating the procedure for $j\rightarrow\infty$, the red intervals are formed over $b_1,\ldots, b_N$. That is, we have at most $N$ red intervals, each containing some $b_i$.

The following figure is an illustration after $j\rightarrow \infty$ in this procedure.

The sum of measures of the red intervals is at most $\sum_{n>N}x_n <(b-a)/2$. Note also that we have at most $N$ disjoint red intervals here (each of those can be any of the forms $(c,d)$, $(c,d]$, $[c,d)$, or $[c,d]$ after $j\rightarrow\infty$ in the process). All members of $\{a_n: n>N\}$ are in the union of these red intervals, and it is dense in $(a,b)$. However, the sum of measures less than $(b-a)/2$ contradicts the density of $(a_n)$.