The general solution to this problem is of importance to crystalline physics and it is known as reciprocal vectors.

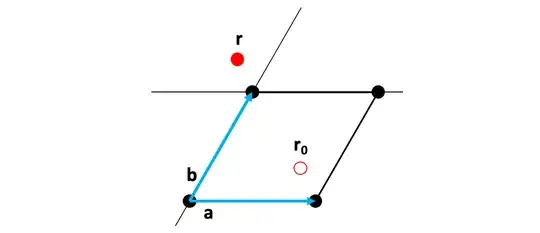

It is pretty easy to understand. You have $\vec a$ and $\vec b$ making your 2D lattice. Create new vectors $\vec c$ and $\vec d$ with the property that $\vec c\cdot\vec b=0=\vec d\cdot\vec a$ and then $\vec a\cdot\vec c=1=\vec b\cdot\vec d$. Then, with whatever initially given vector $\vec r$, you can decompose it as $\vec r=(\vec r\cdot\vec c)\,\vec a+(\vec r\cdot\vec d)\,\vec b$ so that you can do your modulo operation on those coefficients and get the answer.

In crystalline physics, we usually use reciprocal lattice vectors with a slightly different definition, because we care more about parametrising the Brillouin zone. The topic is also connected with the metric and its inverse; you do not actually have to compute those vectors $\vec c$ and $\vec d$ directly if you just want this decomposition. Still, for your current purpose, this is the easiest thing to do.

You had better take care about whether you want results in

$[0,1)$ or in $(-\frac12,+\frac12]$. Your expansion is wrong; the answer is really $(.42265,0.1547)$