First, let me give you some broad resources for doing these kinds of computations. Most of them come down to doing manipulations on ideals, and unfortunately that's not a skill that you usually learn in either a first algebra class or in a first algebraic geometry class! So you kind of have to pick it up on your own. I'll also say that there's very little glory in learning to do all this stuff by hand. It's useful, of course, but just like you would never row reduce a matrix by hand (we have computers for that) you should also make good use of computers to solve problems like these (though, like row reduction, it's still important to know how these algorithms work)! Depending on where you are in your mathematical career, this may feel like cheating. But I assure you it isn't, haha.

I recommend Schenck's Computational Algebraic Geometry as a book that spends a lot of time working out examples in detail. Also Cox, Little, and O'Shea's Ideals, Varieties, and Algorithms is a more comprehensive guide to the computational techniques you can use to solve these kinds of problems. I recommend Sage and Macaulay2 as resources for getting a computer to solve your problems for you.

Now, let's look at your specific questions:

The ideal of the set defined by $f = x^2 + y^2 - 1$ and $g = x-1$ is, of course, the radical $\sqrt{\langle f, g \rangle}$ (do you see why?). So asking if this is equal to $I = \langle f, g \rangle$ as asking whether $I$ is already radical.

Now, we could just hack away at this. Indeed Macaulay2 says:

i1: R = QQ[x,y];

i2: I = ideal (x^2 + y^2 - 1, x-1);

o2: Ideal of R

i3: I == (radical I)

o3 = false

but it would be nice to have some geometric intuition for this. We know $f$ defines the unit circle, and $g$ defines the line $x=1$, so the ideal $\langle f, g \rangle$ defines the intersection of these curves. This intersection is of multiplicity $2$ (since a small perturbation of $g$, say to $x=.9$, intersects the unit circle twice), so the intersection is "the point $(1,0)$, twice". Eventually you'll learn that these high-multiplicity intersections correspond to non-reduced schemes (in fact, maybe now is the time to internalize that. It's one of the big reasons to care about schemes over varieties), so we expect this ideal to not be reduced.

Following up on this geometric intuition, we know this intersection is the point $(1,0)$, whose corresponding ideal is $\langle x-1, y \rangle$ (do you see why?). So we learn that $\sqrt{I} = \langle x-1, y \rangle$. Let's check if this is actually equal to $I$! It's not hard to convince yourself that $y \not \in I$, so $I \neq \sqrt{I}$. After going through this process, you'll likely notice that $y^2 \in I$ but $y \not \in I$ gives a faster (purely algebraic) proof that $I \neq \sqrt{I}$.

For your second question, we want to find the irreducible components of the set defined by $\langle f, g \rangle$ where now $f = x^2 + y^2 + z^2 - 1$ and $g = x^2 - y^2 - z^2 + 1$.

Now we set $I = \sqrt{ \langle f, g \rangle }$, and we "recall" an important fact: Every radical ideal is the intersection of prime ideals. Writing a radical as the intersection of primes amounts to finding the associated primes. Again, we can hack away with Macaulay2:

i1: R = QQ[x,y,z];

i2: I = ideal (x^2 + y^2 + z^2 - 1, x^2 - y^2 - z^2 + 1);

o2: Ideal of R

i3: associatedPrimes I

o3 = {ideal (x, y^2 + z^2 - 1)}

o3: List

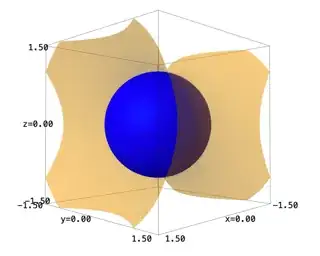

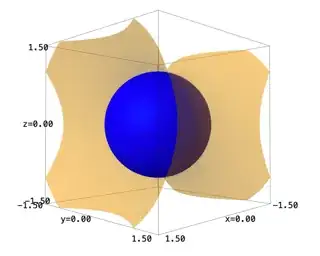

So we see that there's exactly one irreducible component of the intersection! Again, it would be nice to leverage our geometric intuition for this one, so what's the plan? Well, these are simple enough 3d shapes that you might already be able to visualize their solution sets over $\mathbb{R}$. If not, a computer can definitely help with that! Let's plot these surfaces in contrasting colors, and make the outer surface slightly transparent. We can easily do this in sage with code like

implicit_plot3d(x^2 + y^2 + z^2 == 1, (x,-1.5,1.5), (y,-1.5,1.5), (z,-1.5,1.5), color="blue") + implicit_plot3d(x^2 - y^2 - z^2 == -1, (x,-1.5,1.5), (y,-1.5,1.5), (z,-1.5,1.5), color="orange", opacity=0.5)

this creates an interactive 3d graphic of these surfaces. Here's a screenshot:

Playing around with the full interaction makes it believable that the intersection should be a single circle. The sphere seems to sit perfectly inside the hyperboloid. Again, once you have this geometric picture in mind, the algebraic idea becomes clear: eliminating $x$ from $f$ and $g$ gives

$$

1 - y^2 - z^2 = x^2 = y^2 + z^2 - 1

$$

this rearranges to $y^2 + z^2 = 1$, and back substituting we see this can only happen when $x=0$. We recognize the curve $x=0, \ y^2 + z^2 = 1$ as irreducible, so this is our only component! It's given by the ideal $\langle x, y^2 + z^2 - 1 \rangle$, which agrees with Macaulay2's answer.

For your last question, how can we find the points where some rational function is regular?

For an irreducible affine variety $X$ this is fairly easy to answer. The ring of functions $k[X]$ is an integral domain (do you see why?) so that its field of fractions is defined. This field of fractions $k(X)$ is exactly the field of rational functions on $X$, so that every rational function looks like $\frac{f}{g}$ for $f,g \in k[X]$! Even more explicitly, this means that rational functions on $X$ are quotients of polynomials $\frac{f}{g}$ where we say that $\frac{f_1}{g_1} = \frac{f_2}{g_2}$ whenever $f_1 g_2 - f_2 g_1 \in I(X)$.

Now a rational function is undefined exactly when the denominator vanishes! For your example of $1 - \frac{y}{x}$, this is defined whenever $x \neq 0$. That is, everywhere but the two points $(0,1)$ and $(0,-1)$.

There are some minor subtleties here, familiar from a calculus class. For instance, the rational function $\frac{x^2y}{x}$ is actually regular everywhere, even though it looks like it shouldn't be defined at $x=0$. This is really an artifact of a bad choice of representative, since we could have taken $xy$ instead. In case you're working with more general varieties (or worse: schemes) there are even more subtleties to be aware of, but that's probably left to an answer from someone more experienced.

Hopefully this answer conveys the idea that doing the algebra for algebraic geometry becomes easier if you focus harder on the geometry. Hopefully it also conveys that despite this, you can sidestep the geometry and just do hard algebra, if push comes to shove. Indeed, this is the whole beauty of the subject -- the algebra is the same, whether you can picture the geometry or not! That said, if there isn't any underlying geometry to leverage, the algebraic computations can often be brutal, so they're best left to a computer program like Macaulay2. I highly recommend spending some time getting to know it!

I hope this helps ^_^