If you were to take a random piece of a cylinder -- for example, a wedge of random central angle -- the probability of getting a rational volume would be zero, because the rational numbers in the possible range of volumes are countable whereas the real numbers in the possible range of volumes are uncountable.

But likewise the rational multiples of $\pi$ in that same range of volumes are countable, so the probability of getting a rational multiple of $\pi$ is also zero.

In fact you're not looking at a random piece of a cylinder; you're looking at a piece that was constructed in a very particular way. When you do this, you can get effects that "cancel out" a factor of $\pi$.

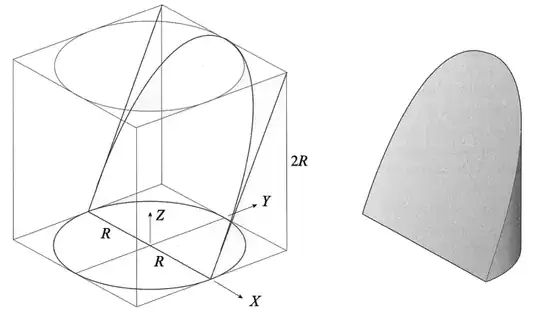

In this case the phenomenon is that due to the scaling of the triangles as you take cross-sections from one end of the diameter to the other,

as illustrated in the paper you cited.

If we were taking these cross-sections from a half-cylinder, the cross-sections would be rectangles of a fixed height and varying widths, and the areas of the rectangles would vary in proportion to the width, which is simply the $y$ coordinate of the graph of the function $y = f(x) = \sqrt{r^2 - x^2}$,

which is a semicircle.

So the volume is simply the height of the half-cylinder times the area of that semicircle.

In the hoof, on the other hand, the cross-sections are right triangles of the same width as the rectangles in the previous paragraph, but the heights of these triangles also vary in proportion to their widths, so the area varies in proportion to the square of width, that is, in proportion to the function $y = g(x) = r^2 - x^2$.

The graph of that function is a parabola rather than a semicircle,

and the area under it does not have the factor of $\pi$ that the semicircle introduces.

So one answer to the question of where the $\pi$ went is that it went into the region between the semicircle and the parabola, and cutting that particular area off the semicircle -- corresponding to cutting off the very particular volume we removed from the half-cylinder to make the hoof -- reduces the area (and volume) from $\pi/2$ times some rational multiple of $r$ to $4/3$ times some rational multiple of $r$.

Compare Volume bounded by cylinders $x^2 + y^2 = r^2$ and $z^2 + y^2 = r^2$, in which we have the intersection of two cylinders. Again there is no $\pi$ in the formula for the volume.

In that case it's because the formula for the volume of the sphere has only one factor of $\pi$ in it, and the intersection of the two cylinders gives you something larger than a sphere by a factor of $4/\pi$.