$x=\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\1&0&1\\0&1&0\end{pmatrix}$, I need to calculate $x^{50}$

Could anyone tell me how to proceed?

Thank you.

$x=\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\1&0&1\\0&1&0\end{pmatrix}$, I need to calculate $x^{50}$

Could anyone tell me how to proceed?

Thank you.

This is a very elementary approach based on finding the general form. If we do $x^2$, we find $$x^2=\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\1&1&0\\1&0&1\end{pmatrix},~~x^4=\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\2&1&0\\2&0&1\end{pmatrix}$$ so I guess that we have $$x^{2k}=\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\k&1&0\\k&0&1\end{pmatrix}$$ An inductive approach adimits this general form is valid for integers $k>0$.

Start by computing $X^2 = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}$.

Since $X^2 = I + N$ where $N^2 = 0$, and what you ask for is $(X^2)^{25} = I^{25} + 25I^{24}N + (\ldots)N^2$, the answer may be found by inspection:

$$ X^{50} = I + 25N $$

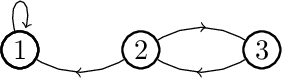

The graph with adjacency matrix $$x:=\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\1&0&1\\0&1&0\end{pmatrix}$$ is drawn below:

For $i,j \in \{1,2,3\}$, the element in cell $(i,j)$ in $x^{50}$ is the number of walks from vertex $i$ to vertex $j$ of length $50$ in the above graph.

We can thus immediately deduce from the graph structure that $x^{50}$ has the form $$x^{50}:=\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\?&1&0\\?&0&1\end{pmatrix}$$ since $50$ is even.

With a bit of thought, we can surmise that there are $25$ walks from vertex $2$ to vertex $1$ of length $50$ (we can land at vertex $1$ after step $1,3,\ldots,49$, after which the walk is determined). Similarly, there are $25$ walks from vertex $3$ to vertex $1$ of length $50$.

Hence $$x^{50}:=\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\25&1&0\\25&0&1\end{pmatrix}.$$

The Jordan Decomposition yields $$ \left[ \begin{array}{r} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \end{array} \right] = \left[ \begin{array}{r} 0 & 0 & 2 \\ -1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array}{r} -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array}{r} 0 & 0 & 2 \\ -1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \end{array} \right]^{-1} $$ Block matrices are easier to raise to a power: $$ \begin{align} \left[ \begin{array}{r} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \end{array} \right]^{50} &= \left[ \begin{array}{r} 0 & 0 & 2 \\ -1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array}{r} -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right]^{50} \left[ \begin{array}{r} 0 & 0 & 2 \\ -1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \end{array} \right]^{-1}\\[6pt] &= \left[ \begin{array}{r} 0 & 0 & 2 \\ -1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array}{r} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 50 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right] \left[ \begin{array}{r} 0 & 0 & 2 \\ -1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \end{array} \right]^{-1}\\[6pt] &= \left[ \begin{array}{r} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 25 & 1 & 0 \\ 25 & 0 & 1 \end{array} \right] \end{align} $$

Evaluate the first few powers and guess $\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\1&0&1\\0&1&0\end{pmatrix}^{2n}$ = $\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\n&1&0\\n&0&1\end{pmatrix}$, proof by induction. Then $x^{50}=\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\25&1&0\\25&0&1\end{pmatrix}$.

Try to prove by induction that: $$ A^n=\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\1&0&1\\0&1&0\end{pmatrix}^n = \begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\ \left\lceil\frac{n}{2}\right\rceil&n+1\bmod{2}&n\bmod{2}\\\left\lfloor\frac{n}{2}\right\rfloor&n\bmod{2}&n+1\bmod2\end{pmatrix} $$

It helps if you start off by calculating a few of the powers by hand, e.g. the first four. We have $$M^2 = \left[\begin{array}{ccc} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 \end{array}\right]$$ $$M^3 = \left[\begin{array}{ccc} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 2 & 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 & 0 \end{array}\right]$$ $$M^4 = \left[\begin{array}{ccc} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 2 & 1 & 0 \\ 2 & 0 & 1 \end{array}\right]$$ My eye picks out a pattern in $M^2$ and $M^4$. Can you prove by induction that $$M^{2n} = \left[\begin{array}{ccc} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ n & 1 & 0 \\ n & 0 & 1 \end{array}\right]$$ Check the case for when $n=1$, then assume that it works for $n=k$, and show that this implies it also holds for $n=k+1$. You should be able to see the final answer.

Try to diagonalize the matrix. Say we could write $X=PDP^{-1}$ where $D$ is diagonal. Then computation would be easy since $X^{50}=PD^{50}P^{-1}$.