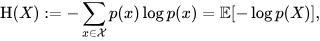

The title is really just an example of the question I want to ask, but I can't think of a more general way to put it in a single sentence. The main difficulty I seem to have with learning math is in understanding how symbols are supposed to be parsed in math notation. Take for example the right side of the definition of information entropy from wikipedia:

I was lucky enough to just learn what the E means in this context (otherwise I wouldn't have even been able to google it since the whole thing is just an image). But even after learning what all symbols mean, my main issue is with p(X) (with the uppercase X). I think it's pretty clear what they're trying to say with the formula. The whole thing is meant to be expanded as p(x1) * -log p(x1) + p(x2) * -log p(x2)... which is the entropy formula. But if I was a computer program that needs to parse the formula, assuming I already have all symbol definitions, how would I do it? I'm not asking this because I want to write such program, but because I'd like to have some clear rules I can follow to understand other formulae which I often am unable to parse even if I know what all the symbols mean.

I have some idea about how it may work, but I'd much rather hear an explanation from someone with more math experience than myself. My idea is that there is an implicit assumption in math that when you have a function typed A -> B, but instead you pass it, for instance, [A, A] then you get back [B, B], or more generally, you find instances of the expected type inside the "shape" that you pass, and then apply the function to each of them and return the same shape.

In the case above, X could be though of as a pair of lists (C, P) where C are possible cases (such as heads or tails) and P are their probabilities, and E just returns the dot product of these lists. Since the function -log p(x) takes a possible case as its input (because that's what p takes), then when we give it the pair (C, P) it'll only operate over the items in C and return back a new pair of lists where all cases have been replaced by applying the function to each of them. For instance if the lists were ([H, T], [1/2, 1/2]) then the function would return ([-log p(H), -log p(T)], [1/2, 1/2]), which then we can pass to E to get -log p(H)*1/2 + -log p(T)*1/2.

In this specific case that seems to work, but I wonder if my reasoning is actually correct in general, or if maybe there's some more general rule one can follow to parse function usage in math when they take the "wrong" datatype.