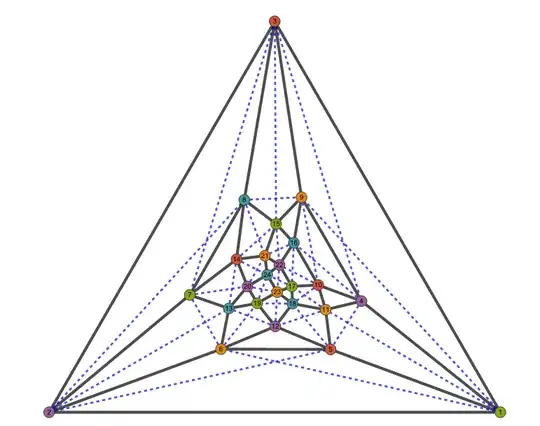

To show that $\chi(G)>4$ we need to argue that there is no proper 4-coloring. As mentioned in the comments, doing this in a nice way often requires a nice description of the graph*. However, because of the prevalence of $K_4$'s in the graph it is tedious but not too difficult to give a "sudoku" proof.

Suppose for sake of contradiction that a 4-coloring $\chi$ exists. WLOG we may assume

$$\chi(1)=1 \quad \chi(4)=2 \quad \chi(9)=3 \quad \chi(3)=4$$

Thus the vertices 5 and 11 must have colors 3 and 4 between them.

Case I. Suppose that indeed

$$\chi(5)=3 \quad \chi(11)=4 $$

We claim that this fixes the "exterior" of the triangle. The vertices 2 and 6 must have colors 2 and 4 between them because of the lower $K_4$, but since $\{2,3\}\in E$:

$$\chi(2)=2 \quad \chi(6)=4$$

Similarly vertices 7 and 13 must have colors 1 and 3 between them, and vertices 8 and 15 must have colors 1 and 2 between them. But since $\{2,8\}\in E$ it must be

$$\chi(13)=1 \quad \chi(7)=3 \quad \chi(8)=1 \quad \chi(15)=2$$

Now go "in one layer" on the right side to see that the vertices 10 and 16 must have colors 1 and 4 between them, and so it must be

$$\chi(10)=1 \quad \chi(16)=4$$

On the other two sides of the triangle we don't have a $K_4$ but vertices 12 and 14 are already adjacent to a lot of determined vertices and we immediately get

$$\chi(12)=2 \quad \chi(14)=4$$

$$\chi(19)=3 \quad \chi(20)=2$$

Therefore vertices 23 and 24 must have colors 1 and 4 between them, and since $\{14,24\}\in E$ we have

$$\chi(23)=4 \quad \chi(24)=1$$

Thus we find a contradiction with vertices 21 and 22: both are adjacent to vertices colored 1, 2, and 4; but they cannot both be colored 3 since they are adjacent.

Case II. To avoid confusion with previous assumptions, change the name of the coloring to $\psi$. We still have

$$\psi(1)=1 \quad \psi(4)=2 \quad \psi(9)=3 \quad \psi(3)=4$$

but now we are supposing that instead

$$\psi(5)=4 \quad \psi(11)=3 $$

Now the vertices 2 and 6 must have colors 2 and 3 between them because of the lower $K_4$, and thus vertices 7 and 13 must have colors 1 and 4 between them. Since $\{3,7\}\in E$:

$$\chi(7)=1 \quad \chi(13)=4$$

As before, vertices 8 and 15 must have colors 1 and 2 between them. But since $\{7,8\}\in E$ and then $\{2,8\}\in E$, it must be

$$\psi(8)=2 \quad \psi(15)=1 \quad \psi(2)=3 \quad \psi(6)=2$$

This fixes the exterior as before. Going in one layer and proceeding in the same way yields

$$\psi(10)=1 \quad \psi(16)=4$$

$$\psi(12)=1 \quad \psi(14)=3$$

This time we find a contradiction faster: we cannot color the vertex 21, since it is adjacent to vertices 15, 8, 14, and 16 which respectively are colored 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Although this argument has obvious disadvantages, it does at least have the benefit of making it quite easy to find a 5-coloring: start with $\chi$ but then when it is time for the contradiction, simply color $\chi(22)=5$ instead, and it is easy to find colors for the last pair of vertices.

I suspect that a proof will require at least as much sudoku as fixing the exterior of the triangle. A more intelligent line of reasoning might proceed by saying: "Okay there are only two ways to make a locally proper coloring around a triangle. But to extend to a global proper coloring we need to be able to make the local colorings agree around each of the eight triangles, and we'll now argue this is impossible."

[ * Misha Lavrov provided such a description in the comments: your graph is the skeleton (just the vertices and edges) of the pseudo-rhombicuboctohedron, with each square face replaced by a $K_4$. Unfortunately it is not the square of the 1-skeleton, since if it were there would be an easy argument. One thing that it is much easier to do with the polyhedron in hand is to chase down Vincent's idea. Breaking the vertices into "layers" it's not hard to argue that any coclique (or independent set, if you prefer) has size at most 6, and so each color class in a 4-coloring must have exactly 6 elements.

Although I think I "see" the proof more clearly with the 3D visual, I didn't find any easier way to write down the argument. In particular, there do exist size-6 cocliques, and it's even easy to get two of them disjoint. I am almost certain that it is possible to find three disjoint ones, but it is not so easy to explain why they cannot be adjusted to add in the fourth. ]