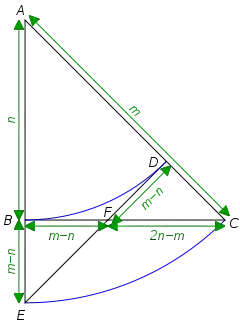

A geometric proof of the irrationality of $\sqrt{2}$ works by constructing two right isosceles triangles with legs $n$ and hypotenuse $m$, and finding in the construction similar triangles with legs $m-n$ and hypotenuse $2n-m$. This shows that $m$ and $n$ can't both be integers as it would lead to infinite descent.

I realise this is really a proof that the hypotenuse-leg ratio of a right isosceles triangle is irrational, and doesn't use the fact that this ratio is equal to $\sqrt{2}$, but that's an aside.

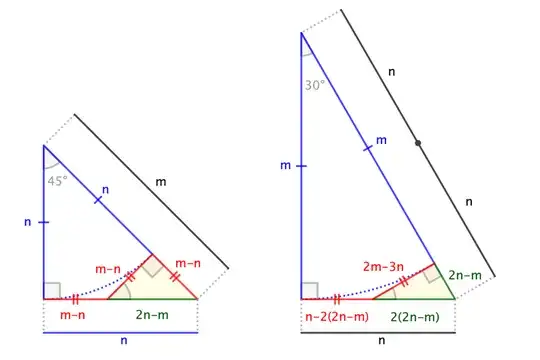

I've been trying to find a geometric construction to prove the irrationality of $\sqrt{3}$ in a similar way. I would expect this to involve 90°–60°–30° triangles. But I keep hitting dead ends.

Can it be done?