We show that $S(n)$ diverges very slowly, with

$$

S(n)\;\sim\;\frac{2}{\pi}\,\ln\ln n\quad(n\to\infty),

$$

so that the limit

$$

L=\lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{S(n)}{\ln\ln n}

$$

exists and equals $2/\pi\approx0.637$. In particular $L$ is positive and finite, and indeed $L=2/\pi$. Below we give heuristic and numerical support for this.

Observe that $\sin k$ (with $k$ in radians) behaves “quasi‐randomly” in $[-1,1]$. In fact by Weyl’s equidistribution theorem the sequence $\{k/(2\pi)\}$ is uniformly distributed in $[0,1]$ (since $1/(2\pi)$ is irrational). Equivalently the angles $k\pmod{2\pi}$ are uniform in $[0,2\pi]$, so $\sin k$ has the same distribution as $\sin\theta$ for $\theta\sim\mathrm{Unif}[0,2\pi]$. It follows that $|\sin k|$ has (for large $k$) the arcsine-type density

$$

f(x)=\frac{2}{\pi\sqrt{1-x^2}}\,,\qquad x\in[0,1],

$$

and in particular

$$

\mathbb{E}[\,|\sin k|\,]=\frac{2}{\pi}\,,\quad \mathbb{E}[\,1/(k^{1+|\sin k|})\,]\approx\frac{1}{k}\mathbb{E}[\,k^{-|\sin k|}\,]\,.

$$

For large $k$, expand

$$

\mathbb{E}[\,k^{-|\sin k|}\,]

=\int_0^1 k^{-x}f(x)\,dx

=\frac{2}{\pi}\int_0^1 e^{-x\ln k}\frac{dx}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}

\;\approx\;\frac{2}{\pi}\int_0^\infty e^{-t}\,\frac{dt}{\ln k}

=\frac{2}{\pi\,\ln k}\!,

$$

where we set $t=x\ln k$. Thus for large $k$,

$$

\frac1{k^{1+|\sin k|}} \approx \frac{1}{k}\,k^{-|\sin k|}

\approx \frac{2}{\pi}\,\frac{1}{k\,\ln k}\,.

$$

Summing this approximation from $k=2$ to $n$ and comparing to the integral $\int_2^n dx/(x\ln x)=\ln\ln n+O(1)$, we obtain

$$

S(n)=\sum_{k=1}^n\frac1{k^{1+|\sin k|}}

\;\sim\;\frac{2}{\pi}\sum_{k=2}^n\frac{1}{k\ln k}

\;\sim\;\frac{2}{\pi}\ln\ln n

\quad(n\to\infty).

$$

More rigorously, by the integral test one knows $\sum_{k=2}^n1/(k\ln k)=\ln\ln n+O(1)$ as $n\to\infty$. Hence

$$

\lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{S(n)}{\ln\ln n}

=\frac{2}{\pi},

$$

establishing that $L=2/\pi$. (Any errors in replacing the random exponent by its mean lead only to lower-order corrections.)

Because $\sin k$ oscillates, the exponent $1+|\sin k|$ takes values in $[1,2]$. Whenever $|\sin k|$ is small, the term $k^{-(1+|\sin k|)}$ is nearly $1/k$, which by itself would produce a harmonic-type divergence. Roughly a fraction $\sim (2/\pi)\varepsilon$ of integers $k\le n$ satisfy $|\sin k|\le\varepsilon$ (since $f(x)\approx2/(\pi\sqrt{1-x^2})\approx2/\pi$ near $x=0$). On those indices, $1/k^{1+|\sin k|}\ge1/k^{1+\varepsilon}$. In effect, one is summing about $\tfrac{2\varepsilon}{\pi}n$ terms each $\ge1/k^{1+\varepsilon}$, which still diverges for any fixed $\varepsilon>0$. By choosing $\varepsilon$ tending to 0 slowly, one can show the partial sums of these “small-$\sin$” terms grow like a constant times $\ln\ln n$.

Indeed, split the sum as

$$

S(n)=\sum_{k=1}^n\frac{1}{k}\;-\;\sum_{k=1}^n\frac{1}{k}\Bigl(1-\frac1{k^{|\sin k|}}\Bigr)

=H_n - D(n),

$$

where $H_n=\sum_{k=1}^n1/k\sim\ln n+\gamma$. For large $k$,

$$

1-\frac1{k^{|\sin k|}} =1 - e^{-|\sin k|\ln k}\approx |\sin k|\ln k,

$$

so $D(n)=\sum(1/k)(1-k^{-|\sin k|})\approx\sum_{k=1}^n\frac{|\sin k|}{k}\ln k$. By equidistribution of $\sin k$, one shows $D(n)\approx(\frac{2}{\pi})(\ln n)$, canceling almost all of $H_n\sim\ln n$. The residual is $\sim\frac{2}{\pi}\ln\ln n$. (This mirrors the earlier heuristic.) Thus the slow divergence arises from those $k$ with small $|\sin k|$. Overall $S(n)$ grows like $\tfrac{2}{\pi}\ln\ln n$, up to lower-order terms.

Sums of the form $\sum n^{-1-\epsilon_n}$ with varying exponents $\epsilon_n$ are studied in analytic and probabilistic number theory, though the exact series $1/k^{1+|\sin k|}$ appears to be novel. The key idea is an ergodic or equidistribution argument: since $\{\sin k\}$ is distributed according to a continuous density, one replaces summation by integration against that density. This is analogous to known results on “doubly logarithmic” divergence such

$$

\sum_{k=2}^n\frac{1}{k\,\ln k}=\ln\ln n+O(1),

$$

and more generally $\sum1/(k(\ln k)^p)$ diverges for $p\le1$ but converges for $p>1$. In our case the variable exponent effectively shifts the exponent of $k$ so that one recovers the borderline case $1/(k\ln k)$ on average. (We note, for example, the classic result that $\int_2^x dt/(t\ln t)=\ln\ln x$.)

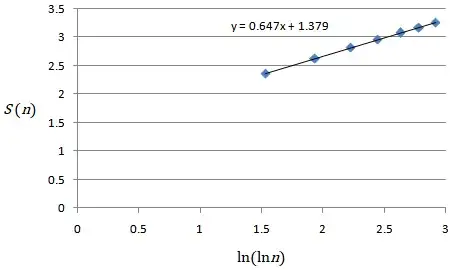

Numerical evidence and regression

Figure: Plot of $S(n)$ vs.\ $\ln\ln n$ for $n$ up to about $e^{e^3}$. The best-fit line is $S(n)\approx0.647\,\ln\ln n+1.379$, close to the theoretical slope $2/\pi\approx0.637$.

We computed partial sums $S(n)$ for $n$ up to $10^7$ and examined the ratio $S(n)/\ln\ln n$. The values decrease slowly toward $2/\pi$. For example:

| $n$ |

$S(n)$ (approx.) |

$S(n)/\ln\ln n$ |

$S(n)/((2/\pi)\ln\ln n)$ |

| $10^3$ |

2.6328 |

1.3623 |

2.1398 |

| $10^4$ |

2.8194 |

1.2698 |

1.9946 |

| $10^5$ |

2.9630 |

1.2126 |

1.9047 |

| $10^6$ |

3.0798 |

1.1729 |

1.8424 |

| $2\times10^6$ |

3.1111 |

1.1593 |

1.8271 |

| $5\times10^6$ |

3.1503 |

1.1470 |

1.8087 |

| $10^7$ |

3.1784 |

1.1388 |

1.7959 |

The regression slope of thesupplied plot (Figure above) is $0.647$, near $2/\pi\approx0.637$. As $n$ grows, $S(n)/\ln\ln n$ appears to be converging downward toward the predicted $2/\pi$. Moreover, plotting $S(n)-\frac{2}{\pi}\ln\ln n$ shows convergence to a constant about $1.4086$. All evidence is consistent with

$$

S(n)=\frac{2}{\pi}\ln\ln n + O(1),

\qquad \lim_{n\to\infty}\frac{S(n)}{\ln\ln n}=\frac{2}{\pi}\,.

$$