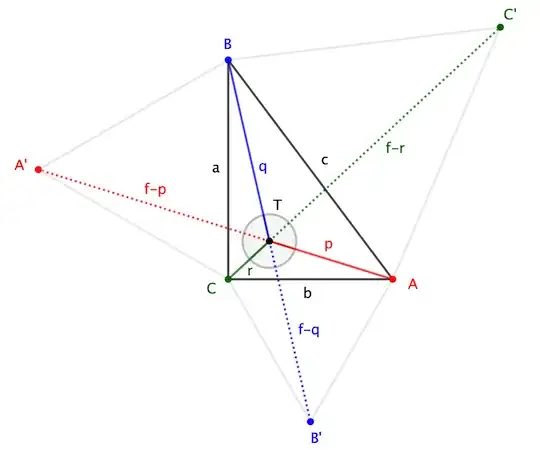

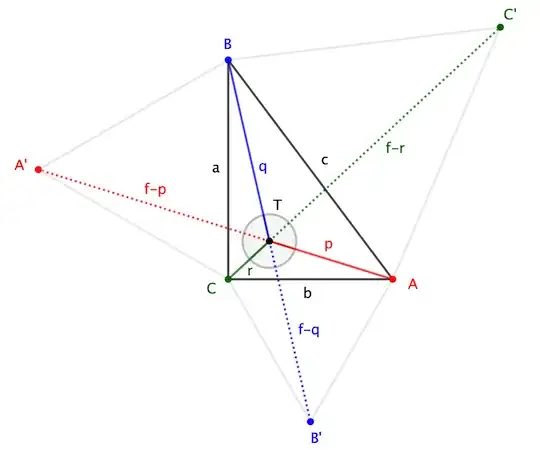

Consider a generic right triangle $\triangle ABC$ right angle at $C$. Define $a := |BC|$, $b := |CA|$, $c := |AB|$ as usual. Let $A'$, $B'$, $C'$ complete external equilateral triangle $\triangle A'BC$, $\triangle AB'C$, $\triangle ABC'$.

It is "known" that lines $AA'$, $BB'$, $CC'$ concur at the Fermat-Torricelli point $T$. Define $p := |TA|$, $q := |TB|$, $r := |TC|$.

Pivoting $\triangle ACA'$ about $C$ causes it to align with $\triangle B'CB$; likewise at other vertices. This implies $|AA'|=|BB'|=|CC'|$; call the common length $f$. (The length is readily calculated —see Note 3 below— but turns out to be irrelevant here, as it will cancel on the way to the final expression.)

Let's setup a system of equations calculating the areas of "$|\triangle ABC| + \text{equilateral}$":

$$\begin{align}

|\triangle ABC| + |\triangle A'BC| &= |\triangle ABA'|+|\triangle ACA'| = \frac12 f ( q + r )\sin 60^\circ \tag1\\

|\triangle ABC| + |\triangle AB'C| &= \phantom{|\triangle ABA'|+|\triangle ACA'|} = \frac12 f ( r + p )\sin 60^\circ \tag2 \\

|\triangle ABC| + |\triangle ABC'| &= \phantom{|\triangle ABA'|+|\triangle ACA'|} = \frac12 f ( p+q )\sin 60^\circ

\tag3 \end{align}$$

These equations become

$$\begin{align}

2ab + a^2\sqrt{3} &= f ( q+r )\sqrt{3} \tag4\\

2ab + b^2\sqrt{3} &= f ( r+p )\sqrt{3} \tag5 \\

2ab + c^2\sqrt{3} &= f ( p+q )\sqrt{3} \tag6 \end{align}$$

Solving for $p$, $q$, $r$, and simplifying with $a^2+b^2=c^2$ gives

$$

p = \frac{b (a + b \sqrt{3})}{f \sqrt{3}} \qquad

q = \frac{a (a \sqrt{3} + b)}{f\sqrt{3}} \qquad

r = \frac{a b}{f\sqrt{3}} \tag7$$

For the problem at hand, we have $a=4$, $b=3$, $c=5$, so that

$$

p = \frac{3 (4 + 3 \sqrt{3})}{f \sqrt{3}} \qquad

q = \frac{4 (4 \sqrt{3} + 3)}{f\sqrt{3}} \qquad

r = \frac{12}{f\sqrt{3}} \tag8$$

and we can calculate

$$\frac{9q+7r}{p} = \frac{36(4\sqrt{3}+3)+84}{3(4+3\sqrt{3})} = \frac{48(4+3\sqrt{3})}{3(4+3\sqrt{3})}= 16 \tag{$\star$}$$

I suspect there's an easier path to this result.

Note. Writing $(\star)$ as

$$ 9 q + 7 r = 16 p$$

it's interesting that the coefficients on $p$, $q$, and $r$ are $a^2$, $b^2$, and $a+b$ ... but the last of these is a bit of an illusion: it's really $a^2-b^2$ (with the coincidence that $a-b=1$). The general relation might be written as

$$\frac{a^2}{q-r} = \frac{b^2}{p-r} \tag{$\star\star$}$$

Note 2. Even if we don't assume $a^2+b^2=c^2$, we still have that $(1-3)$ hold; the expression for $|\triangle ABC|$ doesn't reduce simply to $\frac12ab$, though.

Okay, so writing $|\triangle ABC|$ as the most-convenient form $\frac12bc\sin A$, $\frac12ca\sin B$, $\frac12ab\sin C$ as needed, we can find that

$$p:q:r \;=\; (1 + \cot A \sqrt3) :

(1 + \cot B \sqrt3) :

(1 + \cot C \sqrt3)$$

If we wanted, we could find $P$, $Q$, $R$ such that

$$Pp+Qq+Rr=0$$

by having the "$1$" terms and "$\sqrt{3}$" terms vanish individually. After some simplification, we find

$$\begin{align}

P:Q:R &\;=\; (\cot B - \cot C) : (\cot C- \cot A) : (\cot A - \cot B) \\

&\;=\; \sin A \sin(B-C): \sin B \sin(C-A) : \sin C \sin(A-B)

\end{align}$$

Note 3. In general, we have

$$f^2 = \frac12\left(a^2+b^2+c^2+4\,|\triangle ABC|\,\sqrt{3}\right)$$