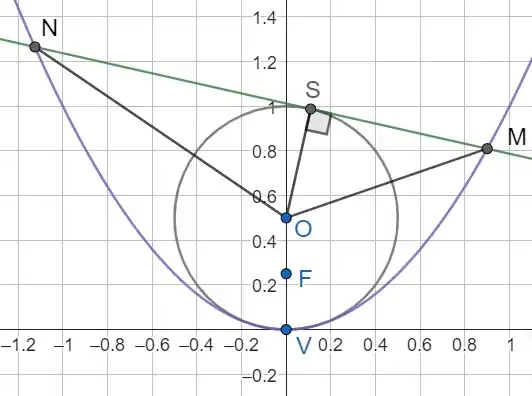

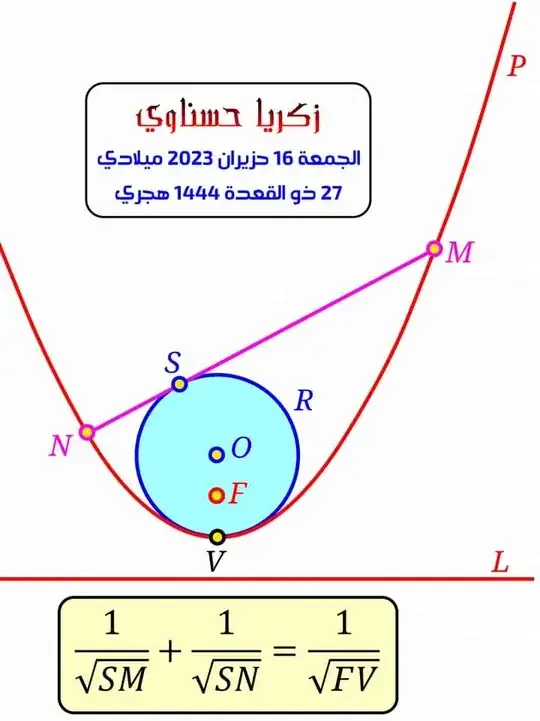

Using the GeoGebra program a few days ago, I came up with a wonderful feature about the parabola and the circle kissing its peak. I don't know if it is new or previously discovered. Please, if it was discovered previously, put a reference mentioning it in the comments, and in any case, can anyone prove it

I don't think a lot of words are needed, this picture includes intuition

- 4,060

- 7

- 25

-

Congratulations on the interesting discovery! (Even if it's known, it was new to you, hence deserving of praise.) ... Please include work you've done on the problem. Your comments to @AnCar's answer suggest that you know a few things about what's happening here. Including such information with the question helps answerers avoid wasting time (theirs or yours) explaining things you already understand. (Be sure to include any context or clarifications in the body of the question itself. Comments are easily overlooked and might be hidden.) – Blue Jun 20 '23 at 03:42

-

God willing, I will do that later – زكريا حسناوي Jun 20 '23 at 03:52

-

The lengths $SM,SN$ are vector lengths, meaning they may take on a negative value when they lie below $S$ and $S$ is in the third or fourth quadrant of the circle – زكريا حسناوي Jun 20 '23 at 04:05

-

Interestingly, I have found that "the name Muharraq refers to the ceremonial burning of deceased corpses since the word muharraq means “burning” in Arabic" ; therefore the connection with "focus" is clear... – Jean Marie Jun 21 '23 at 09:10

-

In Arabic, it is said to be “المحرق” in relation to the property of the reflective mirrors that the parabola enjoys, which makes the rays parallel to the axis of symmetry reflect to gather at one point, and those rays are actually burning. – زكريا حسناوي Jun 21 '23 at 11:05

4 Answers

This is not exactly a pretty solution, since it is entirely based on analytic geometry and it doesn't really offer any insight referring to conics and curvature. I am sure there is a much more clever solution involving some nice invariant of some cleverly chosen transformation of the plane. Alas, I am no geometer and couldn't get one to work. Also no idea if this is a classical problem. The proof is divided into some steps.

Step 1 (Choosing coordinates): By an appropriate combinations of rotations, scaling and translations, we can assume that the directrix $L$ is the horizontal line with equation $y=-1$ and that the focal point is $F(0,1)$. This implies that the parabola will be symmetric around the $y$ axis and that $V$ is the origin of the plane, $V(0,0)$. This means the parabola, viewed as a mapping, will take the form $x\mapsto \alpha x^2$. Solving the equation $|PF|=|PQ|$, where $Q$ is the orthogonal projection of $P$ onto the directrix and $P$ is an arbitrary point of the parabola, quickly gives us that $\alpha=\tfrac{1}{4}$. Therefore, a general point on the parabola will have coordinates $(x,\tfrac{x^2}{4})$.

Step 2 (Osculating circle): By symmetry, it is very clear that the osculating circle will have its center on the $y$ axis. Therefore the center will have coordinates $O(0,c)$ for some positive $c$. Since the circle is tangent to the parabola at $V$, its radius will also be $c$. So the osculating circle will have equation $x^2+(y-c)^2=c^2$ or $y^2-2cy+x^2=0$. Expressing $y$ in terms of $x$ we have $y=c\pm \sqrt{c^2-x^2}$. Fix some small $\varepsilon>0$ and define the function $f:[0,\varepsilon]\to\mathbb{R}$ given by $f(x)=c-\sqrt{c^2-x^2}$ to describe the local behavior of the osculating circle near $V$ (on the positive side, but again we have symmetry). This is clearly differentiable with $f'(x)=\tfrac{x}{\sqrt{c^2-x^2}}$. Define $p:[0,\varepsilon]\to\mathbb{R}$ by $p(x)=\tfrac{x^2}{4}$ to capture the behavior of the parabola on the same neighborhood. Again, this is differentiable with $p'(x)=\tfrac{x}{2}$. The idea now is that if we want to figure out $c$, we need to find the maximum $c$ such that $f'(x)\geq p'(x)$ on $[0,\varepsilon]$. The slope of the circle being at least that of the parabola will guarantee no additional intersections locally and the maximality of $c$ will guarantee that we are taking the largest such circle possible, i.e., the osculating circle. The condition on the derivatives reads $\tfrac{x}{\sqrt{c^2-x^2}}\geq \tfrac{x}{2}$ or $2\geq \sqrt{c^2-x^2}$. So the maximal $c$ is $c=2$. Therefore the osculating circle has center $(0,2)$ and radius $2$.

Step 3 (The easy case when $NM$ is horizontal): Due to symmetry, it is clear that in this case the relevant points are $S(0,4)$ (as the 'north pole' of the osculating circle) and therefore $N(-4,4)$ and $M(4,4)$. Clearly then, $|SN|=4=|SM|$ and the desired equality is easy to check as $|FV|=1$.

Step 4 (The general case of the tangent $NM$): We want to show that $\tfrac{1}{\sqrt{|SN|}}+\tfrac{1}{\sqrt{|SM|}}=1$. Figuring out the correct parametrization of the problem to simplify as much as possible the ugly computations took some time, but inspired by the trivial case above and the intuition that some semblance of a variational argument should be use to prove an invariant, I settled on the idea of regarding the $x$ coordinate of $N$ as a sub unit scalar times the $x$ coordinate in the horizontal case.

In other words, we will think of $N$ as having coordinates $N(-4a,4a^2)$ for some $0<a\leq 1$. In fact, intuition says that the correct interval for $a$ is $(\tfrac{1}{2},1]$ and we will confirm this later. Them $M$ will have coordinates $M(4b,4b^2)$ for some $b\geq 1$. We are therefore looking at the case where the tangent $NM$ has non-negative slope, but again this comes with no loss of generality due to symmetry. Again, on an intuitive level, we expect that the tangent will touch the osculating circle in the fourth quadrant (top left), and we will confirm this later.

A direct computation shows that the equation of the line $NM$ is given by $y=(b-a)x+4ab$. A point $(x,y)$ lying on the intersection of this line and the osculating circle must satisfy the equation $x^2+\big((b-a)x+4ab-2\big)^2=4$. Simplifying, we get \begin{equation} \big(1+(b-a)^2\big)x^2 + 4(b-a)(2ab-1)x+16ab(ab-1)=0.\quad(*) \end{equation}

Crucially, we want a unique intersection point, so the discriminant of $(*)$ must be $0$. After some computations, this leads to \begin{equation} (1-4a^2)b^2+2ab+a^2=0.\quad(**) \end{equation}

$(**)$ leads to two possible solutions for $b$, namely $b=-\tfrac{a}{1+2a}$ and $b=\tfrac{a}{2a-1}$. The first solution would imply $b\leq 0$, so we can discard it and we see that \begin{equation} b=\tfrac{a}{2a-1}. \quad (***) \end{equation} This confirms our prior intuitive remarks. Note that $a$ must be greater than $\tfrac{1}{2}$ and as $a$ approaches $\tfrac{1}{2}$, $b$ goes to infinity. The $y$ coordinate of the tangent point will always be at least $2$, meaning that the correct dependency of $y$ on $x$ for the tangent point $S$ is given by $y=2+\sqrt{4-x^2}$.

Since the discriminant of $(*)$ is $0$, we can find the solution $x=-2\tfrac{(b-a)(2ab-1)}{1+(b-a)^2}$ and plugging $(***)$ yields, after some tedious computations, that \begin{equation} x=-2\tfrac{2a-2a^2}{2a^2-2a+1} \quad \text{ and } \quad y=2\tfrac{2a^2}{2a^2-2a+1} \end{equation} are the coordinates of $S$.

After more tedious computations and some rather 'miraculous' simplifications that suggest a deeper meaning to the problem, we get $\sqrt{|SN|}=2a$ and $\sqrt{|SM|}=\tfrac{2a}{2a-1}$, from which the desired conclusion trivially follows.

- 1,864

-

Nice work. Certainly the proof needs improvement, for example, that the radius of the kissing circle is equal to the distance between the Muharraq and the evidence. It is a well-known rule, so there is no need to calculate it. Likewise, you used a at the beginning to choose the coordinate system, and again you used a to get N, and of course this is incorrect, but in general it worked. Nice, thank you – زكريا حسناوي Jun 20 '23 at 03:15

-

I included the full proof of how to get the radius of the osculating circle for clarity. I am sure it is available in the literature. Your second remark, however, I do not understand. I did not use any $a$ to fix the coordinates. What do you mean? – AnCar Jun 20 '23 at 03:19

-

The equation of the parabola is $ax^2$ and $\sqrt{|SN|}=2a$ does he mean a itself? If this is the case, then this is not correct, of course, because $N$ can be any point of the parabola other than the vertex – زكريا حسناوي Jun 20 '23 at 03:24

-

1English please. Also I think you misunderstand the role of $a$ in the choice of the coordinates of $N$. $a$ is a free parameter there, in $(1/2,1]$. I could have used any letter for that. If by choice of coordinates, you mean that I used $a$ when fixing my parabola, I did not, I used $\alpha$. And again, that is a free parameter. Any letter would work. – AnCar Jun 20 '23 at 03:27

-

Such a strange comment and misunderstanding. The parabola throughout the proof isn't $ax^2$ or even $\alpha x^2$, it is $\tfrac{x^2}{4}$. – AnCar Jun 20 '23 at 03:34

-

In your first comment : I imagine that "muharraq" means "focus" and "evidence" means "directrix"... this is not evident... – Jean Marie Jun 20 '23 at 16:54

-

[+1] I appreciate your solution. I have a different one, but based, as you have it, on a homographic (=projective) correspondence $a'=(pa+q)/(ra+s)$ between the parameters $a,a'$ of the two intersection points, which is not so surprizing. I will write it tomorrow. – Jean Marie Jun 20 '23 at 23:37

-

I have written my answer which has common features with yours. The main simplification is in the last part where I don't need to compute the coordinates of $S$. – Jean Marie Jun 21 '23 at 09:17

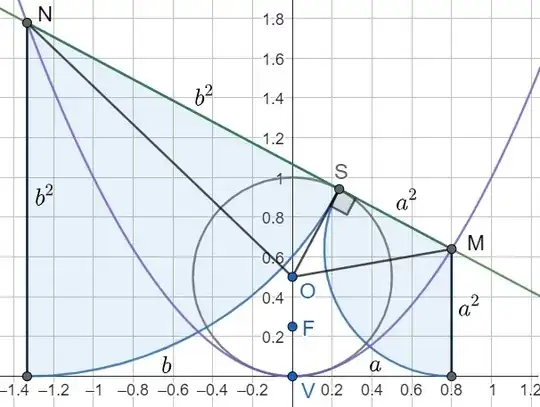

I will establish the property, without loss of generality, for the standard parabola with equation $y=x^2$, knowing that in this case $F=(0,\frac14)$, $O=(0,\frac12)$, with a radius $r=\frac12$ for the circle (see figure).

As any (non vertical) tangent line to the circle intersects the parabola in a point $M$ with abscissa $>\frac12$, we will assume that :

$$M=(a,a^2) \ \text{with} \ a>\frac12.$$

The generic straight line passing through $M$ has equation :

$$y-a^2-m(x-a)=0\tag{1}$$

Let us express that this line is at distance $r=\frac12$ from point $O$ ; by a classical formula :

$$\frac{|\tfrac12-a^2+am|}{\sqrt{1+m^2}}=\frac12\tag{2}$$

Squaring (2) gives the following quadratic equation where the unknown is $m$:

$$1+2(am-a^2)=1+m^2$$

Its roots are

$$m_1=2\frac{a^2-a}{2a-1}, \ \ \ m_2=2 \frac{a^2+a}{2a+1}\tag{3}$$

We need only consider root $m_1$ (in fact, it is the "upper" tangent to the circle issued from $M$) ; it means that (1) gives :

$$y-\frac{2(a^2-a)}{2a-1}(x-a)-a^2=0\tag{4}$$

for the equation of line $MN$.

In order to get the abscissa of $N$ (whose coordinates verify $y=x^2$), using (4), we have to solve the following quadratic equation in variable $x$ :

$$x^2-\frac{2(a^2-a)}{2a-1}(x-a)-a^2=0\tag{5}$$

It has two roots :

$$x_1=a, \ \ \ x_2=\underbrace{\frac{a}{1-2a}}_{f(a)}\tag{6}$$

Of course, only $x_2$ is of interest.

Therefore : $N=(f(a),f(a)^2)$.

Let us compute :

$$OM^2=distance((a,a^2),(0,\tfrac12))^2=a^2+(a^2-\tfrac12)^2=a^4+\tfrac14$$

Applying Pythagoras theorem in right triangle $OMS$ :

$$SM^2+SO^2=OM^2 \ \ \iff \ \ SM^2+(\tfrac12)^2=a^4+\tfrac14,$$

giving the very simple result :

$$SM^2=a^4 \iff \frac{1}{\sqrt{SM}}=\frac{1}{|a|}$$

For a similar reason :

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{SN}}=\frac{1}{|f(a)|}$$

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{SM}}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{SN}}=\frac{1}{|a|}+\frac{1}{|f(a)|}=\frac{1}{a}-\frac{1}{f(a)}$$

(we have taken into account condition $a>\frac12 \implies f(a)<0$). We can conclude :

$$\frac{1}{\sqrt{SM}}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{SN}}=\frac{1}{a}-\frac{1-2a}{a}=2=\frac{1}{\sqrt{FV}}$$

as desired.

Remark : formula (6) defining $f(a)$ is very similar to formula (***) in the answer by @AnCar.

- 88,997

-

1The fact that there exist a homographic (=projective) correspondence $a′=f(a)=(pa+q)/(ra+s$) between the parameters $a,a′$ of the two intersection points $M,N$ could be awaited. I will attempt to find a similar situation where such a correspondance occurs, maybe using tangential equations. – Jean Marie Jun 21 '23 at 09:05

-

1Very nice, thanks for the post. I think your solution might be more 'canonical'. I am not a geometry guy, so I tend to not go for 'refined' geometry solutions when I can find them :). To be fair, the only reason I posted the solution is that I never used the osculating circle for something before, and I find the way of calculating it based on the derivatives pretty fun. – AnCar Jun 21 '23 at 14:39

-

@AnCar In fact, I have found a different solution which I have written as a separate answer. The concept of power of a point with respect to a circle is explained in an answer by Blue here. – Jean Marie Jun 21 '23 at 23:06

-

I arrived at the apex-kissing circle in two ways. The first depends on the distance between the center of the circle that touches the parabola at two points and the middle of the two contacts. The points are equal to the distance between the focus and the guide of the parabola. The second method is that when two parallel tangents are drawn to a circle touching the parabola at the two points, the two lines connecting the four points of intersection will be perpendicular. The two methods depend on the fact that the kissing circle is a special case when the two tangent points apply. – زكريا حسناوي Jun 22 '23 at 08:40

-

There is a third way to arrive at the "apex-kissing circle" that I have explained in my second answer as "Remark 2". – Jean Marie Jun 23 '23 at 16:06

I have already posted an answer. Meanwhile, I have found a more direct solution, where the concept of power of a point with respect to a circle plays the central role. It is why I have decided to present it as a separate answer.

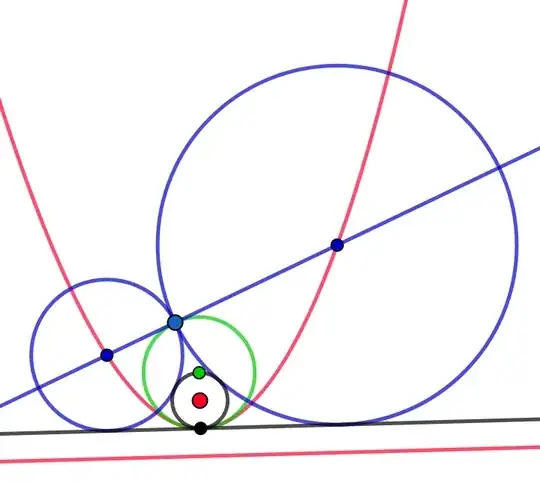

Fig. 1 : Animated version here ; point $M$ is moveable (GeoGebra plot).

Let us consider without loss of generality the particular case of curve $y=x^2$ with "osculating circle" $(C)$ at vertex $V$ (maximal curvature, minimal radius of curvature) with center $O=(0,\tfrac12)$, radius $r=\tfrac12$, therefore with equation :

$$x^2+y^2-y=0\tag{1}$$

with respect to cartesian axes where $V$ is the origin and the abscissa's axis taken along the tangent line $(L)$ to the parabola at point $V$.

Now, consider the identity :

$$x^2-y=\underbrace{(x^2+y^2-y)}_{P_{(C)}(x,y)}-(y^2)\tag{2}$$

where $P_{(C)}(x,y)$ is the power of a generic point in the plane with respect to circle $(C)$ (let us recall that its value is $>0$, resp. $<0$, when the point is outside, resp. inside, circle (C), and zero when $(x,y)$ is on (C) the circle). (2) implies :

$$P_{(C)}(x,y) = y^2 \ \ \iff \ \ y=x^2\tag{3}$$

With words : the parabola is the locus of points $(x,y)$ for which there is equality between $P_{(C)}(x,y)$ and $y^2$.

But the power of a point $M$ exterior to a circle is known to be $MS^2$ where $S$ is the point of tangency of any of the two tangents issued from point $M$ to the circle. Therefore, if we take a tangent line $MN$ (with $M=(a,a^2), \ N=(b,b^2)$ on the parabola) where we assume WLOG that :

$$b<0<a,\tag{4}$$

we just have to add the following constraint : the distance of $O=(\color{red}{0,\tfrac12})$ to line $MN$ is equal to $r=1/2$.

As line $MN$ has equation :

$$-(a+b)x+y+ab=0,\tag{5}$$

$$\text{distance}(O,MN)=\frac{|- (a+b)\color{red}{0} + \color{red}{\tfrac12} + ab |}{\sqrt{(a+b)^2+1}} = \frac12\tag{6}$$

Squaring (4) and simplifying, one gets the constraint :

$$(a-b)^2=4a^2b^2 \ \iff \ (2ab+(a-b))\underbrace{(2ab-(a-b))}_{<0, \text{using} \ (4)}=0 \ \iff \ 2ab+(a-b)=0$$

itself equivalent to :

$$\frac1a - \frac1b=2 \ \iff \ \frac{1}{a} + \frac{1}{|b|}=2 \ \iff \ \frac{1}{\sqrt{SM}} + \frac{1}{\sqrt{SN}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{FV}}$$

Remark 1 : I have had the idea of identity (2) by using the technique of pencil of conics of the form :

$$\underbrace{(x^2+y^2-y)}_{\text{circle (C)}}+\lambda \underbrace{(y^2)}_{\text{tangent (T)}}=0\tag{3}$$

and it appeared that the parabola belongs indeed to the pencil (with $\lambda=-1$ in (3)).

Taking $y^2=0$ instead of $y=0$ for the equation of line $(L)$ is motivated by the fact that it is only with a square that $(L)$ can be considered as a (degenerate) conic curve (twice the equation of the $x$-axis = a pair of lines).

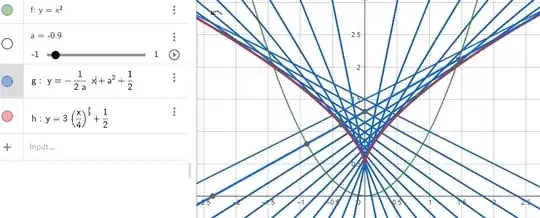

Remark 2 : One can wonder why the center of the osculating circle in $V$ is $(0,1/2)$. Here is an explanation : it is known that the set of centers of curvature of a given curve (here the parabola), called the evolute of this curve, is the envelope of the normals to this curve.

Here, the normal line to the parabola at point $M(a,a^2)$ has equation :

$$y=\frac{1}{2a}x+a^2+\frac12\tag{4}$$

A classical technique (elimination of parameter $a$ between equation (4) and its derivative with respect to parameter $a$) gives the equation of the envelope which is :

$$y=3\left(\frac{x}{4}\right)^{2/3}+\frac12\tag{5}$$

As a consequence, the minimal point $(0,\tfrac12)$ of this curve is the center of the osculating circle in the apex $V$ of the parabola.

Fig. 2 : The locus of centers of curvature of the parabola (evolute curve) in red as envelope of (blue) normal lines to the parabola (GeoGebra plot).

- 88,997

-

1@Blue You might be interested by the present solution. Any comment is welcome. – Jean Marie Jun 21 '23 at 22:58

-

1The solution using the point force concept is more beautiful, and provides a better view of what is happening here, thank you – زكريا حسناوي Jun 22 '23 at 00:43

-

I just used the same technique (power of a point with respect to a circle) in this answer to a question with a figure rather similar to yours (even if the question itself wasn't the same). – Jean Marie Jun 23 '23 at 07:27

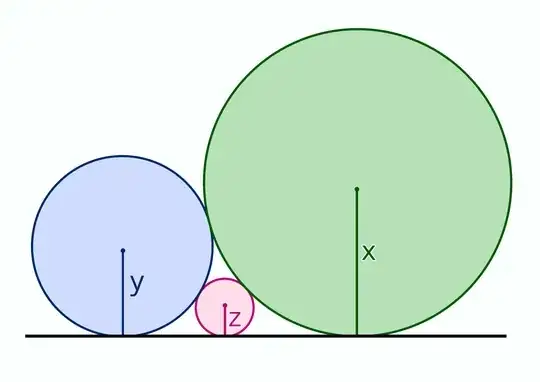

The simplest solution possible is the one that utilizes elementary geometry. I am not currently available to write a full proof, but I can quickly clarify the idea: We know from a special case of Descartes' theorem that:

$\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{y}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{z}}$

Therefore, to prove the theorem, all we need to show is that the two circles in the diagram touch the straight line tangent to the parabola at its vertex:

and then the three circles are clearly formed by defining the parabola.

- 4,060

- 7

- 25

-

[+1] Very clever idea (have you been partly inpired by my last graphics ?). Indeed, it remains to establish that the green circle, homothetic of the black one in a ratio 2:1 is precisely tangent to the blue line. – Jean Marie Jun 26 '23 at 06:52

-

1In fact, I googled /sqrt a+1/sqrt b=1/sqrt c to see other geometric combinations that give the same ratio and to my surprise the first result was relevant. – زكريا حسناوي Jun 26 '23 at 08:18