The following definitions are two definitions of the derivative of $f$.

Definition. (Definition 1) Let $A\subset\mathbb{R}^m$, let $f:A\to\mathbb{R}^n$. Suppose $A$ contains a neighborhood of $a$. We say that $f$ is differentiable at $a$ if there is an $n$ by $m$ matrix $B$ such that $$\frac{f(a+h)-f(a)-B\cdot h}{|h|}\to 0\,\,\,\,\,\,\text{as}\,\,\,\,\,\,h\to0.$$ The matrix $B$, which is unique, is called the derivative of $f$ at $a$; it is denoted $Df(a)$.

Another Definition. (Definition 2) Let $A\subset\mathbb{R}^m$, let $f:A\to\mathbb{R}^n$. Suppose $A$ contains a neighborhood of $a$. We say that $f$ is differentiable at $a$ if there is a linear mapping $B$ such that $$\frac{f(a+h)-f(a)-B(h)}{|h|}\to 0\,\,\,\,\,\,\text{as}\,\,\,\,\,\,h\to0.$$ The linear mapping $B$, which is unique, is called the derivative of $f$ at $a$; it is denoted $Df(a)$.

Suppose we must solve the following problem.

Let $f:\mathbb{R}^2\to\mathbb{R}^2$ be a function such that $f(\begin{pmatrix}x\\y\end{pmatrix})=\begin{pmatrix}e^x\sin y\\x^2 e^y\end{pmatrix}$.

Let $c:=\begin{pmatrix}a\\b\end{pmatrix}$.

Find $Df(c)$.

If we adopt the Definition 1, our answer is like the following:

$Df(c)=\begin{pmatrix}e^a\sin b&e^a \cos b\\2a e^b&a^2 e^b\end{pmatrix}.$

If we adopt the Definition 2, our answer is like the following:

$Df(c)$ is the lienar mapping such that $\mathbb{R}^2\ni \begin{pmatrix}x\\y\end{pmatrix}\to\begin{pmatrix}e^a\sin b&e^a \cos b\\2a e^b&a^2 e^b\end{pmatrix}\begin{pmatrix}x\\y\end{pmatrix}\in\mathbb{R}^2.$

I think Definition 1 is better than Definition 2.

But some authors adopt Definition 2.

I want to know an advantage of Definition 2.

peek-a-boo, Thank you very much for your kind answer.

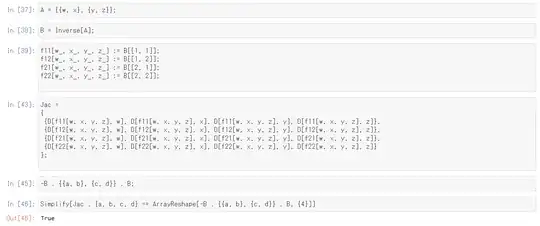

Let $f:GL(2,\mathbb{R})\ni A\to A^{-1}\in GL(2,\mathbb{R})$.

I checked $Df_A(\xi)=-A^{-1}\xi A^{-1}$ holds when $n=2$ by Wolfram Engine. (Please see the answer by peek-a-boo.)