You have $n$ rectangles of area $1$ (and variable height). Pack as many of these rectangles as possible in a semicircle of area $n$. How many leftover rectangles will there be, in terms of $n$?

How to pack the rectangles

I believe that the most efficient way to pack the rectangles is to stack them (so that each rectangle has two vertices touching the arc), as shown below.

What about arranging the rectangles side by side? A simple argument shows that the stacked arrangement is more efficient than the side by side arrangement. In each arrangement, consider a quarter circle (for example the right half of the semicircle). In the stacked arrangement the rectangles have area $1/2$, whereas in the side by side arrangement the rectangles have area $1$. The smaller the rectangles, the more efficient the packing.

Expressing the problem in terms of a sequence

Let $a_k$ be the sequence of the $x$-coordinates of the upper-right vertex of each rectangle, from bottom to top.

We have

$\alpha_1=$ $\large{[}$ largest real root of $2x\sqrt{\frac{2n}{\pi}-x^2}=1$ $\large{]}$

$\alpha_{k+1}=$ $\large{[}$ largest real root of $2x\left(\sqrt{\frac{2n}{\pi}-x^2}-\sqrt{\frac{2n}{\pi}-{\alpha_k}^2}\right)=1$ $\large{]}$

So the number of leftover rectangles is $f(n)=n-$ (number of terms in sequence $\alpha_k$).

I am looking for an exact or asymptotic closed form expression for $f(n)$.

Further thoughts

I have found experimentally that $f(18)=1$ and $f(19)=2$.

Based on Gauss's circle problem, I would guess something like $f(n)\approx n^{\theta}$ for some $\theta<1$. I guess my problem should be easier than Gauss's circle problem, because my problem just depends on finding the number of terms in the well-defined sequence $\alpha_k$.

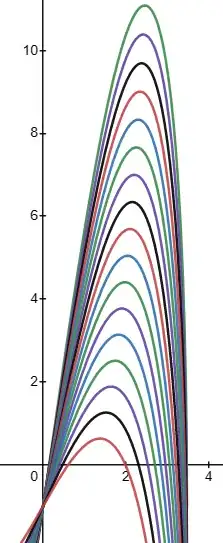

The functions $y=2x\sqrt{\frac{2n}{\pi}-x^2}-1$ and $y=2x\left(\sqrt{\frac{2n}{\pi}-x^2}-\sqrt{\frac{2n}{\pi}-{\alpha_k}^2}\right)-1$ have the following kind of appearance. (This example is with $n=19$.)

If we can find a pattern among the local maximum values, then we can predict how many curves there are, which equals the number of rectangles packed in the semicircle.

On the top curve, $y=2x\sqrt{\frac{2n}{\pi}-x^2}-1$, the coordinates of the maximum point are $\left(\sqrt{\frac{n}{\pi}},\frac{2n}{\pi}-1\right)$.

The gaps between the local maximum values slightly decrease from top to bottom.