Any permutation of an array (we normally don't describe things in terms of "arrays", but it is the same idea, and language you are familiar with) can be broken in cycles as follows: Start with the first location. Where was its content moved to? Okay, the content of that location had to be moved somewhere else to make room. Where did it go? Keep going like that until you encounter the location whose content was moved to the first location. This forms a cycle.

There is no guarantee this cycle included every location in the array. If not, find the first location that was missed, and do the same for it. You cannot encounter a location in the first cycle, as we already know what was moved into it, and it came from somewhere else. Eventually, you will encounter a location that closes the cycle by moving its content to the location you started with. Rinse and repeat. Sometimes your starting location didn't move at all. That is a cycle of length $1$.

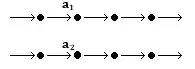

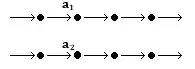

Now that you have broken the permutation $\sigma$ into cycles, suppose you perform a transposition $\tau = (a_1, a_2)$ first, exchanging the contents of locations $a_1$ and $a_2$. Each of $a_1$ and $a_2$ is in a cycle of $\sigma$:

They may be in the same cycle or in different cycles.

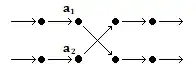

Applying $\tau$ puts the content $C_1$ of $a_1$ in $a_2$. When $\sigma$ is applied afterwords, it moves $C_1$ from $a_2$ to the next location in its cycle, and similarly for the original content of $a_2$:

When $a_1,a_2$ are in different cycles, if we trace the cycle of $a_1$ in $\sigma\tau$, we see that it immediately drops to the lower cycle, then follows that cycle around until it comes back to $a_2$, where it switches back to the upper cycle, and follows it around until it comes back to $a_1$. The two separate cycles of $\sigma$ have been combined into a single cycle of $\sigma\tau$. The remaining cycles of $\sigma$ are completely unaffected by $\tau$, since it didn't change their contents at all. Thus in this case, $\sigma\tau$ has one fewer cycles than $\sigma$.

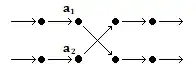

The other case is when $a_1$ and $a_2$ lie on the same cycle of $\sigma$. Following the cycle from $a_1$, we eventually get to $a_2$, and then eventually get back to $a_1$. But in $\sigma\tau$, the swap means that starting from $a_1$, we immediately skip to the successor of $a_2$ and then follow the remainder of the cycle around to $a_1$. Similarly, starting at $a_2$, we immediately skip to the successor of $a_1$ and follow the remainder of the cycle around to $a_2$ again. So the single original cycle in $\sigma$ is now two cycles in $\sigma\tau$, which has one more cycle than $\sigma$. Thus as Angina Seng said in the other thread, $\sigma\tau$ has either one fewer or one more cycle than $\sigma$.

Now to decompose $\sigma$ into transpositions is to show that $\sigma = \tau_1\tau_2\dots\tau_k$ for some $k$, where each of the $\tau_i$ is a transposition. Let $\iota$ be the identity permutation - i.e., it doesn't move anything. Then we can also write $$\sigma = \iota\tau_1\tau_2\dots\tau_k$$.

But note that if a location is unchanged by a permutation, it forms its own cycle of length $1$. Thus for an array of size $n$, the identity permutation $\iota$ has $n$ cycles. And by the argument above, $\iota\tau_1$ must have at least $n-1$ cycles. So $\iota\tau_1\tau_2$ must have at least $n-2$ cycles, and so on. Thus $\iota\tau_1\dots\tau_k$ must have at least $n - k$ cycles. If $\sigma$ has $c$ cycles, then $c \ge n - k$ and so $k \ge n - c$.

A permutation of $n$ elements with $c$ cycles requires at least $n - c$ tranpositions to decompose.