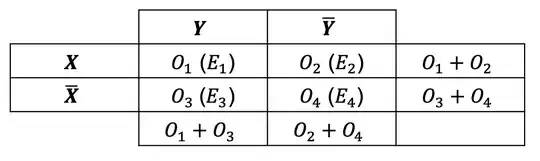

for a 2x2 contingency table, we have for the observed and expected frequencies the following:

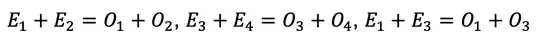

We require e.g. that

which are that the row and column sums have to match between observed and expected frequencies where for the expected frequencies are calculated as e.g. here

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pearson%27s_chi-squared_test#Testing_for_statistical_independence.

With the three equations, we can calculate the forth one. Further more, with these three equations, we can transform the chi-square sum as follows

which are that the row and column sums have to match between observed and expected frequencies where for the expected frequencies are calculated as e.g. here

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pearson%27s_chi-squared_test#Testing_for_statistical_independence.

With the three equations, we can calculate the forth one. Further more, with these three equations, we can transform the chi-square sum as follows

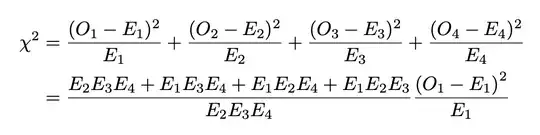

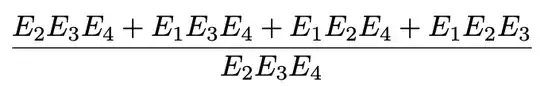

by making a common denominator and using the identities for differences between the observed and expected frequencies from the requirement.

The term

by making a common denominator and using the identities for differences between the observed and expected frequencies from the requirement.

The term

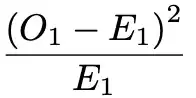

is clearly chi-square distributed with one degree of freedom by definition. However, what is the argument why the factor in front of it

is clearly chi-square distributed with one degree of freedom by definition. However, what is the argument why the factor in front of it

does not change the distribution for the total equation?

does not change the distribution for the total equation?

Is there a change to see that it converges against 1 at least for large expected frequencies or is there a more abstract argument why in spite of that (scaling) factor the second equation in the chi-square calculation is still chi-square distributed with one degree of freedom?

I find only very abstract proofs of the degrees of freedom for a test of independence with a chi-square test in textbooks. So I thought a direct calculation might help to understand this issue of degrees of freedom better. However, I cannot make the last conclusion in this example. So I am very happy for your help.

Thank you

Tim