Here is the text of Rudin, Principles of Mathematical Analysis, chapter $3$, theorem $3.54$:

Let $\sum a_n$ be a conditionally convergent series. Suppose : $$ -\infty \leq \alpha\leq \beta \leq +\infty$$ Then there exist a rearrangement $\sum a'_n$ with partial sums $\{s'_n\}$ such that

$$ \lim\limits_{n\to\infty} \inf s'_n=\alpha \quad \quad \lim\limits_{n\to\infty}\sup s'_n=\beta$$ Let $$p_n = \frac{|a_n| + a_n}{2}, \ q_n = \frac{|a_n| - a_n}{2} \ (n = 1, 2, 3, \ldots). $$ Then $p_n - q_n = a_n$, $p_n + q_n = |a_n|$, $p_n \geq 0$, $q_n \geq 0$. The series $\sum p_n$, $\sum q_n$ must both diverge.

For if both were convergent, then $$\sum \left( p_n + q_n \right) = \sum |a_n|$$ would converge, contrary to hypothesis. Since $$ \sum_{n=1}^N a_n = \sum_{n=1}^N \left( p_n - q_n \right) = \sum_{n=1}^N p_n - \sum_{n=1}^N q_n,$$ divergence of $\sum p_n$ and convergence of $\sum q_n$ (or vice versa) implies divergence of $\sum a_n$, again contrary to hypothesis.

Now let $P_1, P_2, P_3, \ldots$ denote the non-negative terms of $\sum a_n$, in the order in which they occur, and let $Q_1, Q_2, Q_3, \ldots$ be the absolute values of the negative terms of $\sum a_n$, also in their original order.

The series $\sum P_n$, $\sum Q_n$ differ from $\sum p_n$, $\sum q_n$ only by zero terms, and are therefore divergent.

We shall construct sequences $\{m_n \}$, $\{k_n\}$, such that the series $$ P_1 + \cdots + P_{m_1} - Q_1 - \cdots - Q_{k_1} + P_{m_1 + 1} + \cdots + P_{m_2} - Q_{k_1 + 1} - \cdots - Q_{k_2} + \cdots \tag{25}, $$ which clearly is a rearrangement of $\sum a_n$, satisfies (24).

Choose real-valued sequences $\{ \alpha_n \}$, $\{ \beta_n \}$ such that $\alpha_n \rightarrow \alpha$, $\beta_n \rightarrow \beta$, $\alpha_n < \beta_n$, $\beta_1 > 0$.

Let $m_1$, $k_1$ be the smallest integers such that $$P_1 + \cdots + P_{m_1} > \beta_1,$$ $$P_1 + \cdots + P_{m_1} - Q_1 - \cdots - Q_{k_1} < \alpha_1;$$ let $m_2$, $k_2$ be the smallest integers such that $$P_1 + \cdots + P_{m_1} - Q_1 - \cdots - Q_{k_1} + P_{m_1 + 1} + \cdots + P_{m_2} > \beta_2,$$ $$P_1 + \cdots + P_{m_1} - Q_1 - \cdots - Q_{k_1} + P_{m_1 + 1} + \cdots + P_{m_2} - Q_{k_1 + 1} - \cdots - Q_{k_2} < \alpha_2;$$ and continue in this way. This is possible since $\sum P_n$, $\sum Q_n$ diverge.

If $x_n$, $y_n$ denote the partial sums of (25) whose last terms are $P_{m_n}$, $-Q_{k_n}$, then $$ | x_n - \beta_n | \leq P_{m_n}, \ \ \ |y_n - \alpha_n | \leq Q_{k_n}. $$ Since $P_n \rightarrow 0$, $Q_n \rightarrow 0$ as $n \rightarrow \infty$, we see that $x_n \rightarrow \beta$, $y_n \rightarrow \alpha$.

Finally, it is clear that no number less than $\alpha$ or greater than $\beta$ can be a subsequential limit of the partial sums of (25).

I have tried to prove the last two lines of the theorem (from "Finally, it is clear" until the end) but I could use some help in order to formalize the end of my proof.

Proof (inspired from this answer):

Since the series $s_n$ converges $a_n\to 0$, thus $\forall \epsilon >0$ there is an $N$ such that for all $n\geq N$, $$|a_n|<\epsilon$$

Now, consider the quantity $s_n' - \beta $. (We will only treat the case of $\beta$ and show that $s_n' \leq \beta $ for every $n$ superior to a certain $N$)

- If $\alpha = \beta$ we have $\lim \sup s_n' = \lim \inf s_n'$ hence, the limit of $s_n '$ is unique (and we don't need to prove that no number less than α or greater than β can be a subsequential limit of the partial sums).

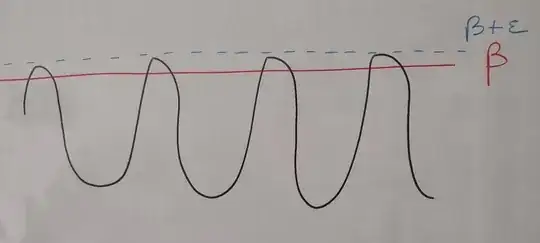

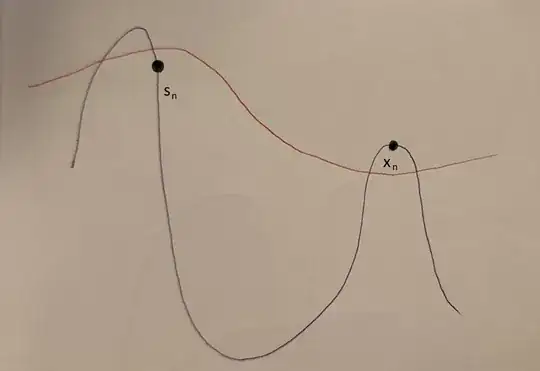

- If $\alpha \neq \beta $, $s_n'$ "oscillates" between $\alpha$ and $\beta$ and its curve is made of peaks (that I drew in the figures below).

$s_n'$ can either coincide with a peak (in which case, there exists $m\in \mathbb N$ such that $s_n' = x_m$) or either not.

If there exists $m$ such that $s_n' = x_m$ then there exists $N\in \mathbb N$ such as $$s_n'-\beta = s_n' - \beta _n + \beta _n -\beta < P_{m_n} + \frac{\epsilon}{2} < \frac{\epsilon}{2} + \frac{\epsilon}{2} < \epsilon $$ for every $n\geq N$

If $s_n'$ is not a peak, then $s_n' - \beta = s_n ' - x_n + x_n - \beta$. This boils down to the previous case, as long as we can prove $s_n' - x_n \leq 0$. This where I could use some help to formalize things.

$s_n$ is not inferior than $x_n$. Drawing of $s_n$ oscillating in blue and $\beta _n$ in red" />

$s_n$ is not inferior than $x_n$. Drawing of $s_n$ oscillating in blue and $\beta _n$ in red" />

As this picture shows, $s_n'$ is not necessarily inferior than $x_n$. Because $s_n'$ can be besides the summit of the previous peak. Previous peak, that is bigger than the peak of $x_n$.

However, at infinity it seems that $s_n' - x_n \leq 0$. For the good reason that all the peaks have about equal heights and that $s_n'$ can't find itself in the same configuration as in the previous picture.

Question:

Is there a way to be more precise, and show analytically (not with a graph) that $s_n' - x_n \leq 0$ for every $n \geq N$ ($N\in \mathbb N$) ?