First part: Generalities on $\mathbb{R}^{3}$:

Let $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ two non-coincident points of a circle on $\mathbb{R}^{3}$ which center is $\mathbf{O} \in \mathbb{R}^{3}$ and radius $R$.

$$\|\mathbf{A}-\mathbf{O}\| = R \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \|\mathbf{B}-\mathbf{O}\| = R$$

There are two unit vectors $\mathbf{u}$ and $\mathbf{v}$ such that it's possible to describe all the points $\mathbf{Q}$ of a circle.

$$\mathbf{Q}(\theta) = \mathbf{O} + \mathbf{u} \cdot R\cos \theta + \mathbf{v} \cdot R\sin \theta$$

For convinience, we say that $\mathbf{Q}(0) = \mathbf{A}$, and $\mathbf{Q}(\theta_0) = \mathbf{B}$

$$\begin{align}\mathbf{A} = \mathbf{Q}(0) & = \mathbf{O} + \mathbf{u} \cdot R \cdot \cos 0 \\

\mathbf{B} = \mathbf{Q}(\theta_0) & = \mathbf{O} + \mathbf{u} \cdot R \cdot \cos \theta_0 + \mathbf{v} \cdot R \cdot \sin \theta_0\end{align}$$

The angle $\theta_0$ is the angle between $\mathbf{A}-\mathbf{O}$ and $\mathbf{B}-\mathbf{O}$:

$$\underbrace{\|\mathbf{A}-\mathbf{O}\|}_{R} \cdot \underbrace{\|\mathbf{B}-\mathbf{O}\|}_{R}\cdot \cos(\theta_0) = \left\langle \mathbf{A}-\mathbf{O}, \mathbf{B}-\mathbf{O} \ \right\rangle$$

As $\cos \theta$ is an even function, there's no sense of direction: If it's clockwise or counter-clockwise. It also causes confusion cause $\arccos$ function maps $\left[-1, \ 1\right] \to \left[0, \ \pi\right]$

For the next step, we say the arc will always begin from $\mathbf{A}$ and go to $\mathbf{B}$.

Example 1: Counter-clockwise

Let $\mathbf{A} = (1, \ 0, \ 0)$, $\mathbf{B}=\left(\dfrac{1}{2}, \ \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}, \ 0\right)$ and $\mathbf{O}=(0, \ 0, \ 0)$

$$\cos \theta_0 = \dfrac{1}{2}$$

Seeing the plane $xy$, if it's clockwise:

$$\theta_0 = \dfrac{5\pi}{3}$$

If it's counter-clockwise:

$$\theta_0 = \dfrac{\pi}{3}$$

Example 2: Clockwise

Let $\mathbf{A} = (1, \ 0, \ 0)$, $\mathbf{B}=\left(\dfrac{1}{2}, \ \dfrac{-\sqrt{3}}{2}, \ 0\right)$ and $\mathbf{O}=(0, \ 0, \ 0)$

$$\cos \theta_0 = \dfrac{\pi}{3}$$

Seeing the plane $xy$, if it's clockwise:

$$\theta_0 = \dfrac{\pi}{3}$$

If it's counter-clockwise:

$$\theta_0 = \dfrac{5\pi}{3}$$

Example 3: 180 degrees

Let $\mathbf{A} = (1, \ 0, \ 0)$, $\mathbf{B}=\left(-1, \ 0, \ 0\right)$ and $\mathbf{O}=(0, \ 0, \ 0)$

$$\cos \theta_0 = -1 $$

Seeing the plane $xy$, it's $\theta_0 = \pi$ clockwise or counter-clockwise

To specify it, we use the vector $\vec{n}$ which relates to the 'axis' or the circle, and the vectors $\vec{u}$ and $\vec{v}$.

$$\mathbf{u} = \dfrac{\mathbf{A}-\mathbf{O}}{\|\mathbf{A}-\mathbf{O}\|}$$

$$\mathbf{V} = (\mathbf{B}-\mathbf{O}) - \mathbf{u} \cdot \langle \mathbf{B}-\mathbf{O}, \ \mathbf{u}\rangle$$

$$\mathbf{v} = \dfrac{\mathbf{V}}{\|\mathbf{V}\|}$$

$$\mathbf{n} = \mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{v}$$

In $\mathbb{R}^2$, if $\mathbf{n} = (0, \ 0, \ 1)$ then it's counter-clockwise, if $\mathbf{n} = (0, \ 0, \ -1)$, then it's clockwise.

Then, to draw an arc, one can do

- Define $\mathbf{n}$, unit vector, to say if it's clockwise or counter-clockwise

- Compute $\mathbf{U} = \mathbf{A}-\mathbf{O}$

- Compute the radius $R$ by taking the norm $L_2$ of $\mathbf{U}$

- Compute $\mathbf{u}$ by diving $\mathbf{U}$ by the radius $R$

- Compute $\mathbf{v} = \mathbf{n} \times \mathbf{u}$

- Compute $\theta_0 = \arctan_{2}(\langle \mathbf{B}-\mathbf{O}, \ \mathbf{v}\rangle, \ \langle \mathbf{B}-\mathbf{O}, \ \mathbf{u}\rangle)$

Take care if $\theta_0$ is negative. It's expected to get $\theta_0 \in \left[0, \ 2\pi\right)$

- For every $\theta \in \left[0, \ \theta_0\right]$ compute the point $\mathbf{Q}$:

$$\mathbf{Q}(\theta) = \mathbf{O} + \mathbf{u} \cdot R\cos \theta + \mathbf{v} \cdot R\sin \theta$$

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

A = np.array([1., 0., 0.])

B = np.array([0., 1., 0.])

O = np.array([0., 0., 0.])

n = np.array([0., 0., -1.])

U = A-O

R = np.linalg.norm(U)

u = U/R

v = np.cross(n, u)

t0 = np.arctan2(np.inner(B-O, v), np.inner(B-O, u))

if t0 < 0:

t0 += 2np.pi

print("u = ", u)

print("v = ", v)

print("n = ", n)

print(f"t0 = {t0:.2f} rad = {(180t0/np.pi):.1f} deg")

theta = np.linspace(0, t0, 1025)

px = O[0] + u[0]Rnp.cos(theta) + v[0]Rnp.sin(theta)

py = O[1] + u[1]Rnp.cos(theta) + v[1]Rnp.sin(theta)

plt.plot(px, py)

plt.axis("equal")

plt.show()

Second part: Bezier curve:

A Bezier curve $\mathbf{C}$ is given by a parameter $u \in \left[0, \ 1\right]$ and by $(n+1)$ control points $\mathbf{P}_i$

$$\mathbf{C}(u) = \sum_{i=0}^{n} B_{i}(u) \cdot \mathbf{P}_i$$

$$B_i(u) = \binom{n}{i} \left(1-u\right)^{n-i} \cdot u^{i}$$

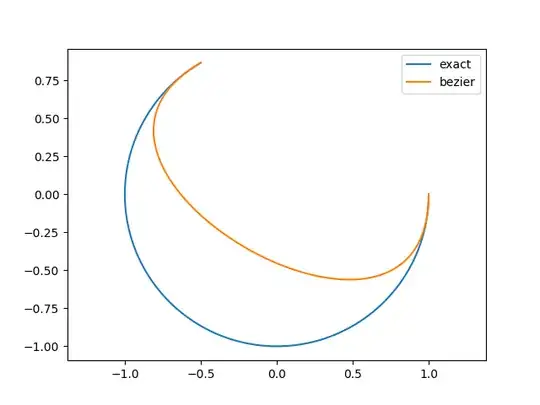

There is no way to describe a circular path by using Bezier curves. To do it exactly, it's necessary to use Rational polynomial functions (NURBS). For example, a $1/4$ circle is given by

$$\begin{align}\mathbf{C}(u) & = \left(\dfrac{1-u^2}{1+u^2}, \ \dfrac{2u}{1+u^2}, \ 0\right) = \sum_{i=0}^{2} R_{i2}(u) \cdot \mathbf{P}_i \\ & = \underbrace{\dfrac{(1-u)^2}{1+u^2}}_{R_{02}} \cdot \underbrace{\left(1, \ 0, \ 0\right)}_{\mathbf{P}_0} + \underbrace{\dfrac{2u(1-u)}{1+u^2}}_{R_{12}} \cdot \underbrace{\left(1, \ 1, \ 0\right)}_{\mathbf{P}_1} + \underbrace{\dfrac{2u^2}{1+u^2}}_{R_{22}} \cdot \underbrace{\left(0, \ 1, \ 0\right) }_{\mathbf{P}_0}\end{align}$$

Although there's no way to do it by using Bezier curves, we can get an approximate shape. The question becomes how to get the $n+1$ control point of Bezier curve.

The first information is the curve $\mathbf{C}$'s extremities must be $\mathbf{A}$ and $\mathbf{B}$:

$$\begin{align}\mathbf{A} & = \mathbf{C}(0) \Rightarrow \mathbf{P}_0 = \mathbf{A}

\\ \mathbf{B} & = \mathbf{C}(1) \Rightarrow \mathbf{P}_{n} = \mathbf{B}\end{align}$$

and set

$$\theta = u \cdot \theta_0$$

- One way of doing it is by computing the tangent vector at the extremities when $n=3$:

$$\begin{align}\left[\dfrac{d\mathbf{C}(u)}{du}\right]_{u=0} & = 3\left(\mathbf{P}_1 - \mathbf{P}_0\right) \\ \left[\dfrac{d\mathbf{C}(u)}{du}\right]_{u=1} & = 3\left(\mathbf{P}_3 - \mathbf{P}_2\right) \end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}\left[\dfrac{d\mathbf{Q}(\theta)}{d\theta}\right]_{\theta=0} & = R \cdot \mathbf{v} \\ \left[\dfrac{d\mathbf{Q}(\theta)}{d\theta}\right]_{\theta=\theta_0} & = R \cdot \mathbf{v} \cos \theta_0 - R \cdot \mathbf{u} \cdot \sin \theta_0\end{align}$$

Now set

$$\begin{align}\mathbf{C}'(0) & = \theta_0 \cdot \mathbf{Q}'(0) \\ \mathbf{C}'(1) & = \theta_0 \cdot \mathbf{Q}'(\theta_0)\end{align}$$

To get

$$\begin{align}\mathbf{P}_1 & = \mathbf{A} + \dfrac{\theta_0 R}{3} \cdot \mathbf{v} \\ \mathbf{P}_2 & = \mathbf{B} + \dfrac{\theta_0 R}{3}\left(\mathbf{u} \cdot \sin \theta_0 - \mathbf{v} \cdot \cos \theta_0 \right) \end{align}$$

- Using the integral by least square

Let $\mathbf{D}(u)$ be the distance between the curve $\mathbf{Q}(\theta) = \mathbf{Q}(\theta_0 \cdot u)$ and $\mathbf{C}(u)$. Then, the objective is to reduce the function $J(\mathbf{P}_i)$:

$$J(\mathbf{P}) = \int_{0}^{1} \|\mathbf{D}\|^2 \ du = \int_{0}^{1} \ \langle \mathbf{D}, \ \mathbf{D}\rangle \ du$$

Then getting the system of equations $\dfrac{\partial J}{\partial \mathbf{P}_i} = 0 \ \ \forall i$ and solving it.