I am trying to understand ring of fractions and I have this question: From ring $\Bbb Z/9\Bbb Z$ determine the different rings of fractions that can be obtained according to the choice of $D$.

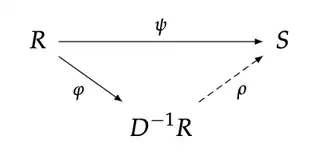

Dummit 7.5: Theorem 15. Let $R$ be a commutative ring. Let $D$ be any nonempty subset of $R$ that does not contain $0$, does not contain any zero divisors and is closed under multiplication. Then there is a commutative ring $Q$ with $1$ such that $Q$ contains $R$ as a subring and every element of $D$ is a unit in $Q$. (The ring $Q$ is called the ring of fractions of $D$ with respect to $R$ and is denoted $D^{-1}R$.)

So, the first thing I did was to find the subset $D$. I consider there are four subsets with this characteristics: $D_1 =$ {1}, $D_2 =$ {1, 8}, $D_3 =$ {1, 4, 7}, $D_4 =$ {1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8}. Then, I wrote the elements of $D_1^{-1}R$, nine elements, so I claim is isomorphic to $\Bbb Z/9\Bbb Z$. The same way, $D_2^{-1}R$, nine different elements again and this ring would be isomorphic to $\Bbb Z/9\Bbb Z$.

I am not quite sure of my procedure, feels like I'm doing something wrong. I would really appreciate your help to guide me on the right way, or any advice to find those different ring of fractions.