EDIT: I just learnt that it might not be a good practice to post images of pages of textbooks on MSE. Sorry: I don't have the time now to OCR everything in this answer (nor I possess the sufficient amount of mathpix snips—which became limited since they turned into freemium software). Either some generous editor might convert the images into text (please delete this paragraph if you do so) or me myself in the future along with some fully free OCR+LaTeX software I'll do it. In the meantime, in-text I referenced the sections in Bourbaki.

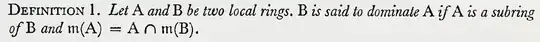

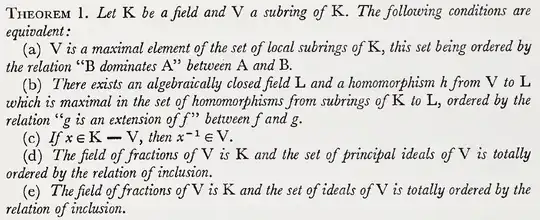

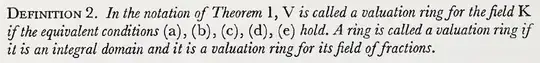

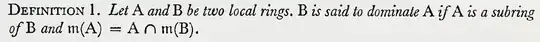

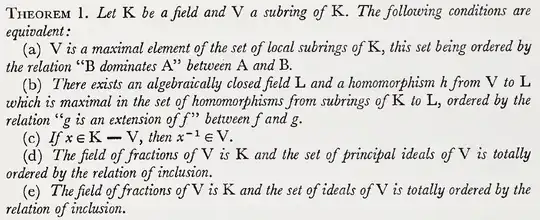

I think I prefer Bourbaki's definition to Harsthorne's one for valuation rings (the following is Bourbaki's Commutative Algebra, Ch. VI, §1, no. 1,2):

We will argue below the equivalence between Bourbaki's and Hartshorne's definitions for valuation ring. From now on we will adhere to Bourbaki's one.

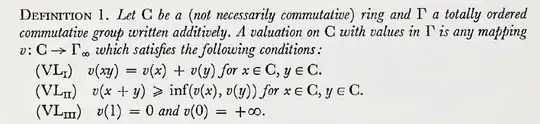

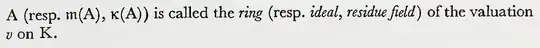

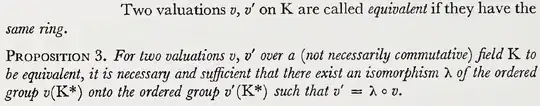

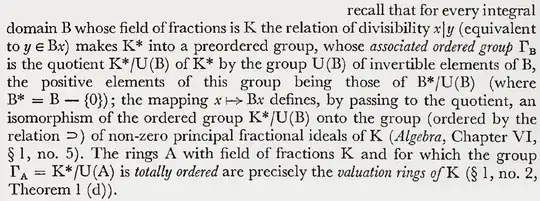

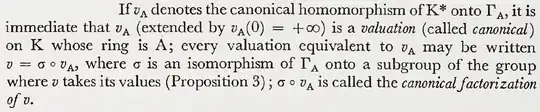

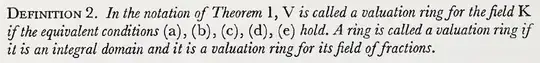

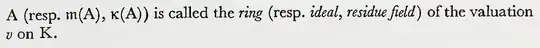

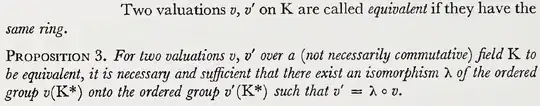

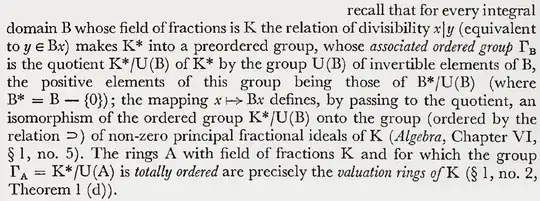

Let's explore the relation of valuation rings with valuations. I will let Bourbaki state the definition for a general valuation and the result for valuations on fields. (The following is ibid., § 3, no. 1,2.)

Note that (v) means that $A$ is a valuation ring of $K$. This result means that Hartshorne's definition for valuation ring implies Bourbaki's one (it's not difficult to show that (v) implies $K=\operatorname{Frac}A$).

Hence, if $K$ is a field and $A$ is a valuation ring of $K$, then if a surjective valuation of $K$ whose ring is $A$ were to exist, it would be unique up to unique isomorphism (note that any valuation $v$ on $K$ gives a surjective one by restricting to the image of $v$). Answering your question “how do we know that there aren't any other valuations taking different values that give back the same ring?”: if there are, then they will be isomorphic (after restricting to the image of the valuations).

Existence is argued by Bourbaki after Proposition 3:

Indeed, since the ordered group $\{Ax\mid x\in K\}$ (isomorphic to $K^*/U(A)$) contains as an ordered submonoid the monoid of principal ideals in $A$ (call it $P(A)$), we deduce that $K^*/U(A)$ totally ordered implies $P(A)$ totally ordered, i.e., $A$ is a valuation ring of $K$ (Definition 2 above). Conversely, suppose $P(A)$ is totally ordered, and let $x, y \in K$. Write $x=a/b, y=c/d$, where $a,b,c,d\in A$. We have that either $Aad \subset Acb$ or $Aad\supset Acb$. Dividing by $bd$, we get $Ax\subset Ay$ or $Ax\supset Ay$.

Hence, Bourbaki's definition for valuation ring implies Hartshorne's one.

The existence plus uniqueness up to unique isomorphism result entitles us to speak about the (onto) valuation of a valuation ring of a field. On the other hand, to each valuation ring $A$ we find attached an invariant: its value group (by definition, if $v$ is a valuation on $K=\operatorname{Frac}A$ with ring $A$, its value group is $v(K\setminus\{0\})$); it is an totally ordered group uniquely determined by $A$ up to unique isomorphism of ordered groups.