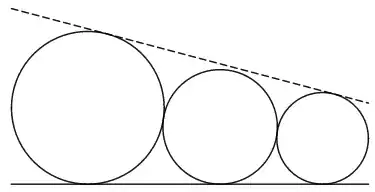

Three disks are placed on the ground like this:

From left to right, their radii are $\frac{1}{x-1}, \frac{1}{x}, \frac{1}{x+1}$ metres. They lie in a plane perpendicular to the ground. The middle disk touches the other two disks.

Using only paper and pen, approximate the value of $x$ such that the middle disk is tangent to the line that is tangent to and above the other two disks. You may assume that the earth is a sphere of radius $R$ metres.

(Before you read the last sentence, it seems like there's something wrong with the question, because it seems like the middle disk should never touch the line. But the ground is actually a circular arc of the earth, so the middle disk is "pushed up" and touches the line for some value of $x$.)

The answer turns out to be, elegantly, $x\approx R/2$. But the algebra seems to be horrendous and I needed to use my computer to find the answer.

My attempt

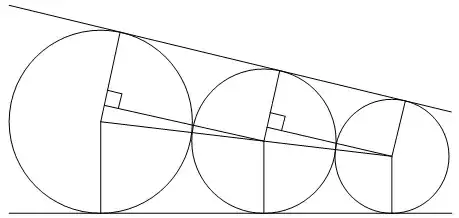

Call the angles at the centre of the middle disk $A, B, C, D, E$ with $A$ at the lower-left and going clockwise.

$A=\arccos{\left(\dfrac{\left(\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{x-1}\right)^2+\left(R+\frac{1}{x}\right)^2-\left(R+\frac{1}{x-1}\right)^2}{2\left(\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{x-1}\right)\left(R+\frac{1}{x}\right)}\right)}$

$B=\arcsin{\left(\dfrac{\frac{1}{x-1}-\frac{1}{x}}{\frac{1}{x-1}+\frac{1}{x}}\right)}$

$C=\dfrac{\pi}{2}$

$D=\arccos{\left(\dfrac{\frac{1}{x}-\frac{1}{x+1}}{\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{x+1}}\right)}$

$E=\arccos{\left(\dfrac{\left(\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{x+1}\right)^2+\left(R+\frac{1}{x}\right)^2-\left(R+\frac{1}{x+1}\right)^2}{2\left(\frac{1}{x}+\frac{1}{x+1}\right)\left(R+\frac{1}{x}\right)}\right)}$

We assume that the middle disk is tangent to the line that is tangent to and above the other two disks. This implies:

$$A+B+C+D+E=2\pi$$

I am utterly unable to approximate $x$ without a computer, even after attempting to simplify it. And yet the computer-assisted answer is just $x\approx R/2$. Can $x$ be approximated without a computer?

(This question was inspired by a frame challenge.)

"... the line for sufficiently large values of x"because it feels like as x becomes very Large the radii become extremely small, thereby the curvature of the ground they are placed on becoming insignificant. – mrtechtroid Jan 15 '23 at 12:59