I'm reading about differential forms and I have the following example. Let $M= \{(x,y,z) \in \Bbb R^3 \mid x^2+y^2+z^2 < 1 \}$ and consider the $2$-form $\omega = x dy \wedge dz - y dx \wedge dz+zdx \wedge dy.$ We can now integrate $\omega$ over $\partial M$ as follows.

We have that $$\begin{align*}dx &= \cos(u)\cos(v)du - \sin(v)\sin(u) dv \\ dy &= \cos(u)\sin(v)du + \cos(v)\sin(u) dv \\ dz &= -\sin(u)du \end{align*}$$

and the wedge products are $$\begin{align*}dx \wedge dy &= \cos(u)\sin(u)du \wedge dv \\ dx \wedge dz &= -\sin(v)\sin^2(u) du \wedge dv \\ dy \wedge dz &= \sin^2(u)\cos(v)du \wedge dv \end{align*}$$

and we get that $\omega = \sin(u) du \wedge dv.$ Thus integrating $$\int_{\partial M} \omega = \int_{0}^{2\pi}\int_{0}^\pi \sin(u) dudv = 4\pi.$$

What I don't get here is that what is the interpretation of this $2$-form $\omega$. I can see that the integral checks out by looking at the definitions, but I have no understanding what is $\omega$ representing.

What is the use of integrating over something that one cannot understand. Even in this case we're just integrating something over the boundary of the unit disc in $\Bbb R^3$ and yes the output is some number, but I have no idea what can I conclude from this.

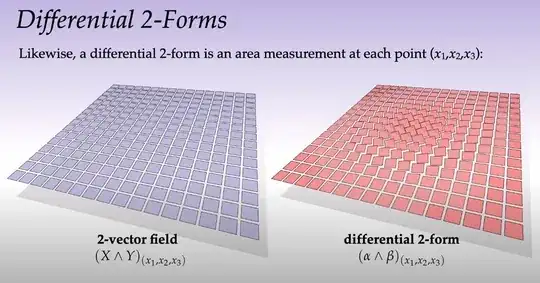

I have been watching this lecture series by Keenan Crane and he does a really nice job on visualizing these things, but it's still not clicking for me quite yet.

He's given the following visualizations and what I'm trying to do is to figure out how they apply for example in the integral above. Can this even be done?