Since if you use the derivative, you are taking for granted that the derivative exists at the point $(1, 4)$, we might also use another approach that relies on that assumption, too, but avoids the use of the derivative.

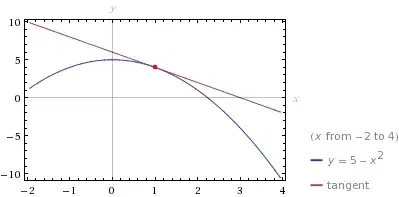

We observe that a tangent line is also a line that (a) touches the curve in question at the specified point, and (b) is everywhere else one side or the other of the curve (either above or below)*. Criterion (a) is satisfied trivially by any line that goes through point $(1, 4)$, since $4 = 5-1^2 = 5-1$.

Now, we will consider two different forms of lines passing through $(1, 4)$. The first is simply the line $x = 1$. However, it can be seen that this line contains the points $(1, 3)$ and $(1, 5)$, and since those two points lie below and above the curve, respectively, the line $x = 1$ is not tangent to that curve.

The second form is the more general equation

$$

y-4 = m(x-1)

$$

which we might rewrite as

$$

y = mx+(4-m)

$$

If we subtract the quadratic from the linear equation, we get

$$

\Delta y = x^2+mx-(m+1)

$$

This is a parabola that we "want" to have one double root in order for the line to be tangent to the original curve $y = 5-x^2$. According to the quadratic formula, this parabola has one double root when the determinant $m^2+4(m+1) = 0$. That is,

$$

m^2+4m+4 = 0

$$

which yields the unique solution $m = -2$. Therefore, the equation of the tangent line must be $y = 6-2x$. We can verify that this line is tangent by observing that the difference $\Delta y$ is given by

$$

\Delta y = x^2-2x+1 = (x-1)^2

$$

which is always positive, so the line is always above the parabola.

*If we insist on rigor, this answer is incomplete, since we have not shown that the parabola does indeed divide the plane into two portions, above and below (and there may be other things I've missed besides, depending on your standards).