Here is an answer of sorts: It is more of a long comment aimed to help you to understand the shortcomings of your post.

First of all, there is a confusion in your question:

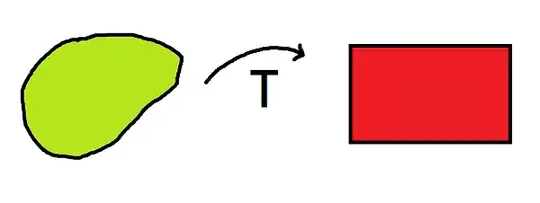

"This led me to wonder if there's a change of variables possible for every integral such that it results in integration over constant limits, ie, it would map the region of integration to a rectangle."

In fact, in order to achieve integration with constant limits, one has to use a map going in the opposite direction: From a rectangle (or a cube as in the current title) to the original domain of integration.

Nevertheless, since you use the (wrong in my opinion) direction of the map thrice in your post (once in the title, once in the above sentence and once in a picture), so be it.

In either case, let's first try to figure out what kind of maps qualify as "change of variable maps"? Typical undergraduate calculus textbooks address this question by ... simply ignoring it and using the terminology as if it so clear to everybody that discussing this notion is completely unnecessary.

Let me, at least, assume that the maps in question are surjective and you are asking for the existence of a surjective (aka onto) map $f$ from the given (compact) $C\subset {\mathbb R}^d$ to the unit cube $Q\subset {\mathbb R}^d$ (I will assume that $d\ge 1$). A further question is of the regularity of such a map (this vague notion pertains to properties such as continuity and differentiability of maps).

Here are several quick examples proving that such a map (regardless of its regularity) does not always exist.

Example 1. $C$ is empty.

Example 2. $C$ is finite.

Example 3. $C$ is countably-infinite (and compact), for instance, $C=\{0\}\cup \{\frac{1}{n}: n\in {\mathbb N}\}$.

Since these sets are (at most) countable, they do not admit surjective maps to uncountable sets such as $Q$.

However, once you assume that $C$ has the cardinality of continuum (for instance, this is the case provided that every point of $C$ is an accumulation point of $C$ and $C$ is nonempty), then $C$ admits a bijective (one-to-one and onto) map to $Q$. This is something that you learn when taking an upper-division math class. However, maps used in such constructions have no use in calculus since they (frequently) lack any degree of regularity. Hence, let me assume that change-of-variables maps are at least continuous. (Actually, opinions differ even here and some commonly used change-of-variables are discontinuous, but are "piecewise-continuous"!) However, let me stick with continuous maps. Then, seemingly, you are in luck:

Theorem. Every compact subset $C\subset {\mathbb R}^d$ of the cardinality of continuum admits a surjective continuous map $f: C\to Q$.

I will not explain a proof of this theorem (one can find these in books on general topology). A good example of such a map is the "Cantor function" (or "devil's staircase function") mapping the usual "ternary" Cantor set continuously onto the unit interval $[0,1]$. However, such maps, while continuous, are still not regular enough to be useful for the purpose of the change of variables: In many cases, they are non-differentiable and, hence, you cannot talk about their Jacobians.

Now, if you like a specific example:

The ternary Cantor set does not admit a differentiable surjective map to the unit interval.

Does this answer your question? I am not sure. Maybe you do not assume differentiability of your maps, maybe you do not even assume continuity. At least, it provides you with an example to ponder. Now, if (as in the title) you meant to ask "Which Cantor subsets of ${\mathbb R}$ admit surjective differentiable maps to the unit interval $[0,1]$?" the answer becomes: Precisely those, which have positive Lebesgue measure. Would such maps qualify as "change of variable maps"? It is up to you to decide.