From http://mathinsight.org/dot_product:

$\LARGE{1. }$ "The dot product of $\mathbf{a}$ with unit vector $\mathbf{b}\backslash|\mathbf{b}|$ is defined to be the projection of $\mathbf{a}$ in the direction of $\mathbf{b}\backslash|\mathbf{b}|$, or the amount that $\mathbf{a}$ is pointing in the same direction as unit vector $\mathbf{b}\backslash|\mathbf{b}|$."

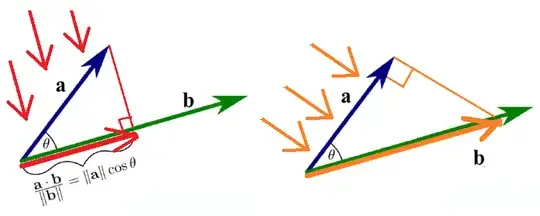

To obtain "the amount that $\mathbf{a}$ is pointing in the same direction as unit vector $\mathbf{b}\backslash|\mathbf{b}|$", why not define dot product as the orange vector instead of the red vector? The red arrows denote light rays perpendicular to $\mathbf{a}$; the orange arrows denote light rays perpendicular to $\mathbf{b}$.

$\LARGE{2. } $ "We want a quantity that would be positive if the two vectors are pointing in similar directions, zero if they are perpendicular, and negative if the two vectors are pointing in nearly opposite directions. We will define the dot product between the vectors to capture these quantities."

Unfortunately, the above link does not explain: Why do we want these properties?

$\LARGE{3. }$ What is the motivation behind the symmetry of the dot products in $\mathbf{a}$ and $\mathbf{b}$ ?

I have referenced How to understand dot product is the angle's cosine? et Understanding Dot and Cross Product.

$\Large{\text{Supplement to Chris Culter's Answer:}}$

$\Large{\#1.1.}$ I'll let $\diamond$ denote the dot product as depicted in the orange, that which results from a projection induced by light rays perpendicular to $\mathbf{b}$.

How did you divine/foreknow that $\mathbf{x \diamond b} + \mathbf{y \diamond b} \neq \mathbf{(x + y) \diamond b ?}$

Thanks to your answer, I found a counterexample which I present underneath your Answer below.