This is a mathematical and algorithmic question, so I hope it is not flagged for failing to be a pure mathematical question.

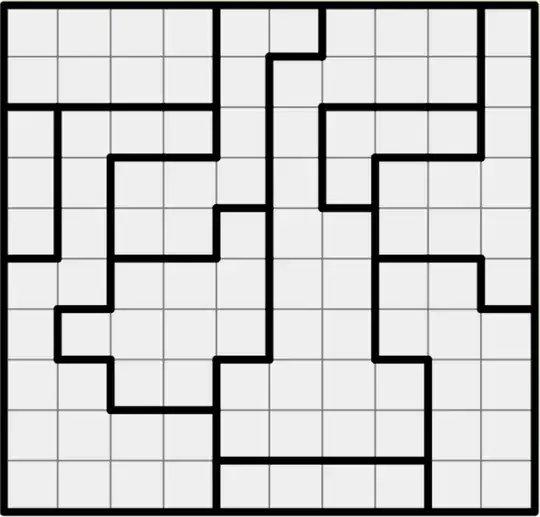

The puzzle "Two not touch" (or Star Battle) consists of a $10 \times 10$ grid array fully tiled with irregularly shaped contiguous regions, for instance:

The task is to place (20) stars in the grid cells such that:

- There are exactly two stars in each row

- There are exactly two stars in each column

- There are exactly two stars in each contiguous tiled region

- No two stars "touch," that is, are adjacent vertically, horizontally, or on diagonally adjacent squares

My question isn't about how to solve such a puzzle. It is instead how to algorithmically/mathematically create a valid puzzle that has a (single) unique solution, as such puzzles ensure.

I have little doubt that the first step is to randomly assign two cells (for "virtual stars"... where the solution stars must fall) in each row and each column in a blank (un-tiled) grid, obeying the "not touch" constraint. This is quite a simple algorithm.

Next comes drawing the tiled regions. It is fairly straightforward to draw contiguous regions that bound just two of the virtual stars.

Question: How does one ensure that the tiled regions admit just a single unique puzzle solution?