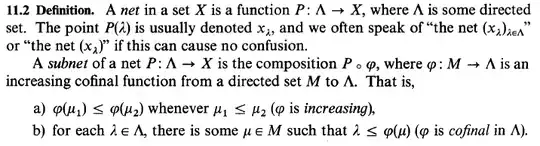

At the chapter 4-th in the text General Topology Stephen Willard give the following definition

Now the function $\varphi$ in the previoius definition must not be necessary strictly increasing so that with respect this definition a subsequence $(x_{n_l})_{l\in\omega}$ of a injective sequence $(x_n)_{n\in\omega}$ could be costant, that is it is possibile there exists $n\in\omega$ such that $$ n_l=n $$ for any $l\in\omega$. However at the chapter 3-th in the text Topology James Munkres gives the following definition.

which requires that a subsequence of an injective sequence must be injective: anyway sometimes Munkres use the symbol $\subset$ to mean $\subseteq$ so that I supposed that here he does a similar thing but obviously I canno be sure.

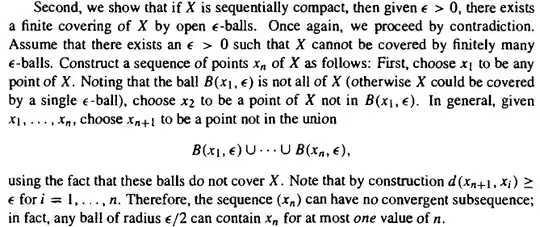

Now let's prove that if $X$ is sequentially compact then given any $\epsilon>0$ there exists a finite covering of $X$ by open $\epsilon$-balls.

So I would like to discuss why $(x_n)_{n\in\omega}$ cannot have any convergent subsequence: indeed if $(x_{n_l})_{l\in\omega}$ was a subsequence converging to $x$ then there would exists $l_\epsilon\in\omega$ such that $$ x_{n_l}\in B\Big(x,\frac\epsilon 2\Big) $$ for any $l\ge l_\epsilon$ so that in particular for any $l\ge l_\epsilon$ the inequality $$ \begin{equation}\tag{1}\label{eq:simple1}{d(x_{n_l},x_{n_{l_\epsilon}})\le d(x_{n_l},x)+d(x,x_{n_{l_\epsilon}})<\frac\epsilon 2+\frac\epsilon 2=\epsilon}\end{equation} $$ holds but $(n_l)_{l\in\omega}$ must be strictly increasing by Munkres definition so that we conclude that $(x_{n_l})_{l\in\omega}$ does not converges. So is true that Munkres definition requires that $(n_l)_{l\in\omega}$ is strectly increasing? Is Munkres definittion usual? is Willard definition unusual? If Munkres definition does not requires injectivity how prove that $(x_{n_l})_{l\in\omega}$ does not converges? So could someone help me, please?