I have $(X_i)$ an i.i.d sequence of random variables in $L^1$.

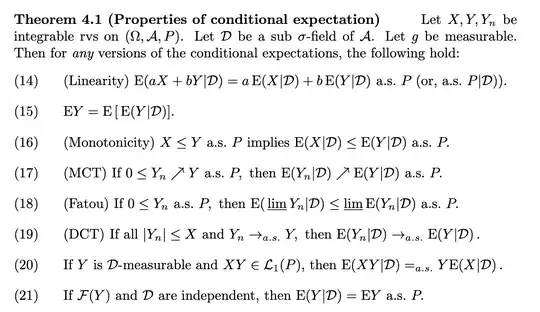

Now I want to compute $\Bbb{E}\left(\sum_{k=1}^n X_k|X_1\right)$. I know that this is equal to $\sum_{k=1}^n\Bbb{E}\left( X_k|X_1\right)$ i.e. the problem reduces to compute $\Bbb{E}(X_k|X_1)$. But somehow I don't see how I can compute this conditional expectation. Could maybe someone help me?

We have the following definition:

If $X\in L^1$ and $B\subset A$ a sub sigma algebra, then $\Bbb{E}(X|B)$ is the unique r.v. $\xi\in L^1$ such that for all $Q\in L^\infty$ $$\Bbb{E}(XQ)=\Bbb{E}(\xi Q)$$