Given the following definitions of a convex function from Spivak's Calculus:

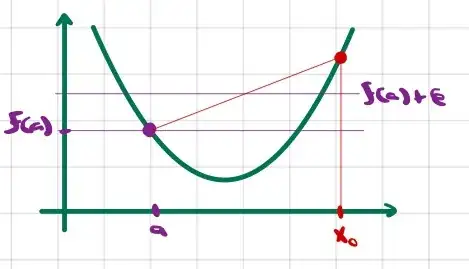

Definition 1: A function $f$ is convex on an interval, if for all $a$ and $b$ in the interval, the line segment joining $(a,f(a))$ and $(b,f(b))$ lies above the graph of $f$.

Definition 2: A function $f$ is convex on an interval if for all $a, x$, and $b$ in the interval with $a<x<b$ we have $\frac{f(x)-f(a)}{x-a}<\frac{f(b)-f(a)}{b-a}$.

First question: Does Definition 2 mean that $f$ has to be defined everywhere in an interval to be convex in that interval?

Second question: Is it possible to prove that such a function is always continuous? If so, how?

Here is my attempt at a proof. I'm going to outline the proofs, without actually proving using $\epsilon$ and $\delta$ proofs as would be required to be rigorous. If the general idea of each case below is sound, then I think the corresponding rigorous proofs are relatively simple.

Let $f$ be convex. Assume $f$ is discontinuous at some point $a$, ie $\lim\limits_{x \to a} f(x) \neq f(a)$.

My proof strategy is to go through each of the possible ways that $f$ could be discontinuous at $a$ and show that they violate convexity of $f$.

Removable discontinuities aren't possible if $f$ must be defined at every point in an interval to be convex.

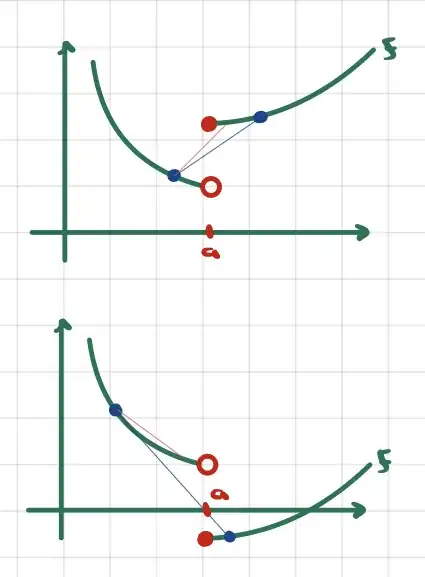

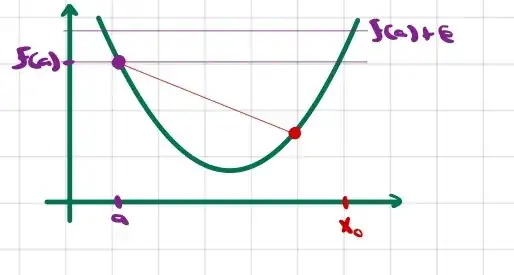

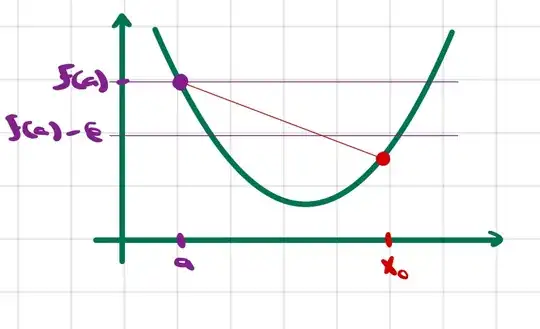

Jump discontinuities aren't possible for a convex function, due to the following two situations:

In both cases above, the light red line has a slope that is larger than the slope of the blue line, and this violates convexity.

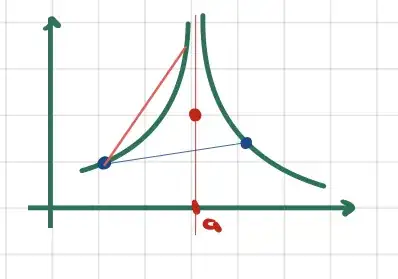

Essential discontinuities aren't possible because the slope between any point $x_1<a$ and a point $a+h$ can be made arbitrarily high. Just choose an $h_1>0$ and an $h_2<0$, let the slope between $x_1$ and $a+h_1$ be some value. Then we can always find an $a+h_2$ with a larger slope, violating convexity as in the picture below.

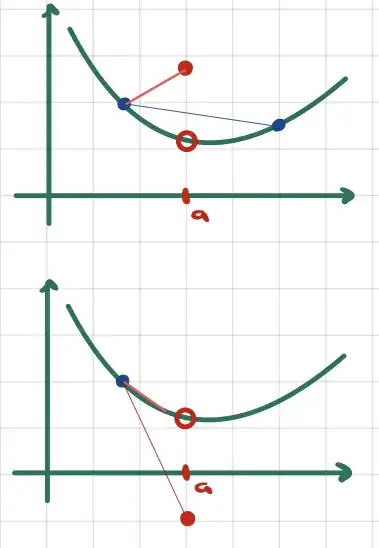

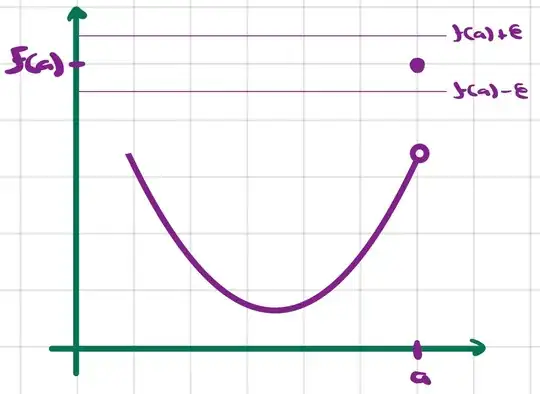

Finally, consider the case of a point discontinuity

Whether $f(a)>\lim\limits_{x \to a} f(x)$ or $f(a)<\lim\limits_{x \to a} f(x)$, convexity is violated.

In all possible cases, $f$ turns out not to be convex, a contradiction.

Therefore, by proof by contradiction, we conclude that $f$ must be continuous at every point.

Is this approach (proof by possible cases of discontinuity, showing contradiction in each one) correct?