I am not sure if this is a new problem but it is one that I thought up and have been working on for some time. Alas, I have been unable to develop a complete solution to the problem and would be interested if there are any useful techniques or insights that the community could provide.

I am looking for the continuous PDF $X$ that exists over $[0,1]$ and has the following relationship with is transformation:

\begin{equation} X \sim \frac{n}{n+X} \end{equation}

where $n \overset{iid}{\sim} U(0,1)$. What I am trying to convey here is that taking any number of transformations of the form $\frac{n_1}{n_1+X}$, $\frac{n_2}{n_2+X}$, etc. does not change the distribution $X$ for which we are looking. Furthermore, successive transformations such as $\frac{n_2}{n_2+\frac{n_1}{n_1+X}}$ and so on result in the same distribution $X$ for which we are looking.

Attempt 1

The first approach I took was took was to try to solve for $X$ by solving for the combination of random variates $n_1, n_2, ...$ and then performing the transformation on them. This became very messy and very quickly. Alas, this solution did not provide the limiting distribution but it did provide an insight.

Each successive addition of a random variate changed the distribution for $X$. Therefore, it did not seem that standard substitution techniques may be helpful with this type of problem.

Attempt 2

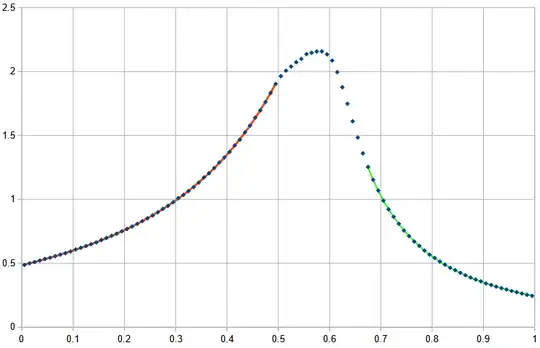

I noticed that the distribution on the interval from $[0,\frac{n}{n+1}]$ was always in the form of $\frac{c}{(X-1)^2}$, where $c$ is some constant. If this was the form of the limiting distribution for that interval, then perhaps I could apply the transformation on that segment of the distribution to gain insight about the remaining distribution $X$. This too became very messy, very quickly but with the help of Mathematica, I was able to get an approximation of the distribution which would seems much closer to the real distribution than in my first attempt. The results I obtained were (apologies for the math wall):

\begin{align} \frac{-X+(1-2 X) \log \left(\frac{X}{2 X-1}\right)+1}{2 (X-1)^2 (2 X-1)} && \frac{2}{3}\leq X<1 \\ \frac{1}{48} (-25) \left(6 \text{Li}_2(-3)-3 \left(\text{Li}_2\left(\frac{1}{4}\right)+6\right)+\pi ^2-6 \log ^2(2)+\log (3) \log (64)+\log (2985984)\right) && 5 X=3 \\ \frac{\text{Li}_2\left(\frac{1}{4}\right)+4+2 \log ^2(2)-3 \log (3)}{4 (X-1)^2} && 0<X\leq \frac{1}{2} \\ \frac{12 (2 X-1) \text{Li}_2\left(\frac{X-1}{2 X-1}\right)-48 X+\pi ^2 (2 X-1)+12 ((2 X-1) \log (1-X)-2 X) \log (X)+12 \left((1-2 X) \log \left(-\frac{(X-1) X}{2 X-1}\right) \log (2 X-1)+X \log ((3-2 X) X-1)\right)-24 \tanh ^{-1}(1-2 X)+36}{24 (X-1)^2 (2 X-1)} && \frac{3}{5}<X<\frac{2}{3} \\ \frac{\text{Li}_2\left(\frac{1}{4}\right) (2 X-1) (2-3 X)^2-2 (2-3 X)^2 (2 X-1) \text{Li}_2\left(\frac{X}{3 X-2}\right)+2 (2 X-1) (2-3 X)^2 \text{Li}_2\left(\frac{1-2 X}{2-3 X}\right)+33 X^2 \log \left(\frac{54}{X}-81\right)+2 \log \left(\frac{1}{X-1}+3\right) \left(21 X^2+\left(33 X^2+4\right) \log \left(\frac{X}{2 X-1}\right)\right)+2 \left(-9 X^3 \log \left(-27 (2-3 X)^2\right)+X \left(9 X^2 \log ((X-1) X)+2 \left(9 X^2+10\right) \log \left(\frac{2}{X}-3\right) \log (2 (X-1))+33 X \log \left(\frac{2 (X-1)}{3 X-2}\right) \log \left(\frac{X}{2-3 X}\right)+10 \log \left(\frac{X}{54-81 X}\right)\right)+\log (X-1) \left(-2 \left(9 X^2+10\right) X \log \left(\frac{2}{X}-3\right)-\left(33 X^2+4\right) \log \left(\frac{1-2 X}{3 X-2}\right)+16 X\right)+\left(\left(33 X^2+4\right) \log \left(\frac{1-2 X}{3 X-2}\right)-16 X\right) \log (3 X-2)\right)-\frac{1}{6} (2 X-1) (2-3 X)^2 \left(\pi ^2-12 \left(3+\log ^2(2)\right)\right)+\log \left(\frac{1}{(X-1)^8}\right)-4 \log (X)+8 \log \left(\frac{2 (X-1)}{3 X-2}\right) \log \left(\frac{X}{2-3 X}\right)+12 \log (6-9 X)}{4 (2 X-1) \left(3 X^2-5 X+2\right)^2} && \frac{1}{2}<X<\frac{3}{5} \\ 0 && X>1\lor X<0 \\ \text{Indeterminate} && \text{True} \\ \end{align}

Unfortunately, this approach does not seem to work well beyond the first two iterations and this is the best approximation I can get.

Observation

There may not be a feasible closed form solution to this problem. It seems as if the intervals for the individual sections may continue to break in accordance with fractions associated with the Fibonacci numbers: 1/2, 3/5, 8/11, etc. I haven't proven yet that this is indeed the case but if it is that way then a closed form solution is certainly not possible.

Additional Desire I am not sure if this is yet possible either but I am trying to track how the maximum value of the distribution progresses over time. Even if there is no closed form for this distribution I wonder if there is a way that you can find a closed form solution for the maximum value of for the values for $x=0,1$.

As always, I appreciate any insights from the math hive mind!