Consider a projectile thrown from a point (a,b) so as to reach point (c,d) in minimium intial possible speed ((c>a and d>b )) is it possible to show that happens when the intially velocity and the final velocity angle are at 90° with respect to each other? ( I have shown this using trajectory equation amd differentiating ). But i was curious if properties of parabolas are useful which can easily prove this neat fact ? [Gravity is there hence parabolic path]

-

Edited @Intelligentipauca sir – ProblemDestroyer Mar 26 '22 at 12:44

-

What do you mean by "in minimum speed"? Is it the minimum speed at $(a,b)$, at $(c,d)$, or in minimum time? The projectile is exposed to two forces: the throw and gravity. It therefore cannot be a motion by a constant speed, better: by a constant velocity. – Marius S.L. Mar 26 '22 at 12:52

-

Yeah its initial minimum speed – ProblemDestroyer Mar 26 '22 at 12:59

-

I found that initial velocity is minimum when initial velocity is perpendicular to final velocity. But I haven't a simple proof. So it seems your statement is false but something near to it is true: is that only a coincidence, or you did it on purpose? – Intelligenti pauca Mar 27 '22 at 08:36

-

I am really sorry @Intelligentipauca just realized that problem mentioned was that only what you were saying . – ProblemDestroyer Mar 27 '22 at 09:13

-

Intially i was having this query from a long time so i wasnt able to collect it from where i got it but i was able to gather it now – ProblemDestroyer Mar 27 '22 at 09:14

3 Answers

I don't know if it's possible to get a purely geometric proof without considering the physics at all, but we can try to abstract as much of the physics away as possible. The key part that I think we need to preserve is that the parabolic motion is a composition of two motions:

- A displacement in the direction of the projectile's initial velocity that grows linearly with elapsed time. The constant of proportionality depends on the magnitude of the initial velocity.

- A displacement in the direction "straight down" that grows as the square of elapsed time. The constant of proportionality depends on gravity and is the same regardless of the speed or direction in which the projectile is launched.

It follows that if we construct the displacement of the projectile by combining these two components, for a given magnitude of initial velocity (which determines the downward component will be proportional to the square of the component in the direction of the initial velocity. The constant of proportionality will depend only on the magnitude of the initial velocity and on gravity.

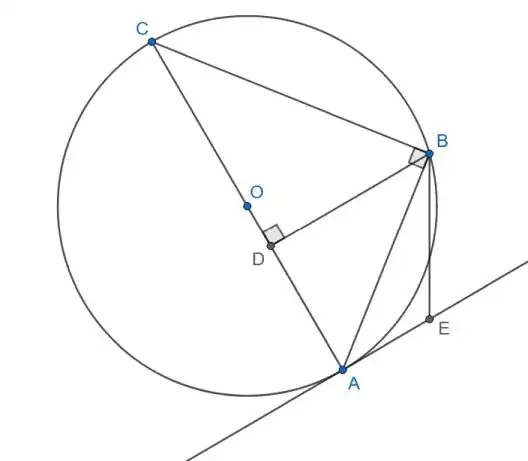

Now consider a circle with an inscribed right triangle $\triangle ABC$:

Let $D$ be the foot of the perpendicular dropped from $B$ to the diameter $AC.$ Then triangles $\triangle ABC$ and $\triangle ADB$ are similar. We find that $$ \frac{AB}{AC} = \frac{AD}{AB} $$ and therefore $AD = \frac{1}{AC} (AB)^2. $ If we hold $A$ and $O$ fixed but allow $B$ to vary, the length $AD$ will be proportional to $(AB)^2,$ and if we choose a "vertical" direction in the plane, the segment $BE$ parallel to that "vertical" direction from the point $B$ to a point $E$ on the line tangent to the circle at $A$ also will be proportional to $(AB)^2.$

This gives us a way of combining a displacement $AB$ in an arbitrary direction (whatever the direction of the initial velocity is) with a downward component $BE$ proportional to the square of $AB$. Provided that we choose a magnitude of velocity so that the constants of proportionality come out to the right values, and provided we use the same magnitude of initial velocity in any direction, a projectile launched from $A$ in the direction toward $B$ will hit the point $E$ on the line tangent to the circle at $A.$

If we choose a larger initial velocity, the projectile will travel farther than $AB$ before falling a distance $BE$ from the line in its initial direction of travel. This can be modeled by a larger circle tangent to the same line at $A$. If we choose a smaller initial velocity, we can use a smaller circle tangent to the same line at $A.$

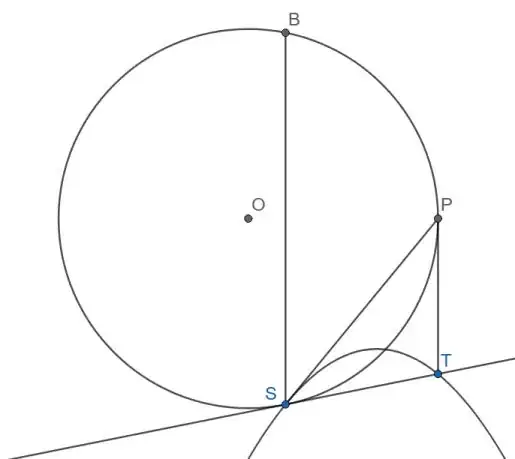

Now let $S = (a,b)$ be the point you launch the projectile from and $T = (c,d)$ be the point you want it to reach. Construct a line through $S$ and $T.$ Construct a line through $T$ that goes "straight up and down", that is, in the direction of gravity. Construct a circle tangent to the first line at $S$ and tangent to the second line at $P$. You will then have most of the parts of the figure below:

Note that the circle must be tangent to the first line at $A$ in order to use the model we previously developed. But if the circle were large enough to intersect the line $PT$ in two places, it would represent a larger initial speed than the circle tangent to the line at $P$, whereas the circle for any smaller initial speed would be smaller and would not intersect the line $PT$ at all, hence the projectile would not reach $T$ for any initial launch direction. Therefore the circle shown above, tangent to one line at $A$ and the other line at $P$, represents the circle for the smallest initial velocity at which a projectile can reach $T.$

Now let $B$ be the point that is directly "above" $S$ (that is, $BS$ is parallel to $PT$). Then $P$ bisects the smaller arc $BS$, and therefore $SP$ bisects the angle $\angle BST.$

The conclusion is that in order to reach a point $T$ at minimum initial velocity, starting at a point $S$, you want to launch the projectile at an angle exactly halfway between "straight up" and the direction from $S$ to $T.$ A well-known special case occurs where the line $ST$ is horizontal (perpendicular to the "straight up" direction), in which case the minimum-speed launch angle is $45^\circ$ above horizontal.

Now we need to find the angle at which the projectile arrives at $T.$ I'm sure there is a way to find this angle using only pure geometry and the information already developed, but I'll take a physical shortcut: the trajectory of a projectile (on a flat non-rotating Earth with no air resistance) is reversible, so if we take the velocity at which the projectile reaches $T$ and launch it back in the opposite direction from which it arrived, it will trace the parabola back to $S.$ A second part of the physical shortcut is the observation that any increase or decrease in the speed at $T$ would correspond to an increase or decrease in speed at $S$; so the speed at which we launched the projectile from $T$ is the minimum at which it could reach $S.$

In short, the tangent to the parabola at $T$ must bisect the angle $\angle PTS.$

Given that fact, and the fact that $\triangle PTS$ is isosceles, the tangent to the parabola at $T$ is perpendicular to $PS,$ which is the tangent to the parabola at $S,$ which is what you wanted to prove.

By the way, the circle in this answer is also found via coordinate geometry (and some Galilean relativity) in this answer.

Additionally, although I will not attempt to prove it in this answer, the directrix of the parabolic trajectory is the horizontal line through the midpoint of $OS$ (the point midway between the center of the circle and the tangent point). The intersection of the directrix and $BS$ is the point that would be the apex of the trajectory if the projectile were launched straight up.

- 108,155

-

By abstracting physics way you mean trying to use as less physics as much as possible ? Sir . I understood your method though which is pretty interesting . – ProblemDestroyer Mar 28 '22 at 00:19

Not exactly what the question is asking (no geometry here) but at least I found a way to get the result without calculus. That might give some hint for a better solution.

Let's set first of all: $\Delta x=c-a$ and $\Delta y=d-b$, while $g$ is the acceleration due to gravity, $t$ the time taken by the projectile to reach the final point and $(v_{0x},v_{0y})$ the horizontal and vertical components of initial velocity $v_0$. The equations of motion give then: $$ v_{0x}={\Delta x\over t}, \quad v_{0y}={\Delta y\over t}+{1\over2}gt. $$ Inserting these into $v_0^2=v_{0x}^2+v_{0y}^2$ one gets: $$ v_0^2={L^2\over t^2}+{1\over4}g^2t^2+g\Delta y, $$ where I set $L^2=\Delta x^2+\Delta y^2$. As $g\Delta y$ is constant, $v_0^2$ is minimum when the first two terms are minimum, and by AM-GM inequality that happens when both terms have the same value, which gives: $$ v_{0\min}^2=Lg+g\Delta y \quad\text{and}\quad t_\min = \sqrt{2L\over g}. $$ On the other hand we know from kinematics (or by energy conservation) that $g\Delta y={1\over2}(v^2-v_0^2)$, where $v$ is the final velocity. Inserting this into the above expression leads to: $$ {1\over2}(v^2+v_0^2)_\min=Lg. $$ Finally, squaring $\vec v-\vec v_0=\vec g t$ one obtains $$ \vec v\cdot\vec v_0={1\over2}(v^2+v_0^2-g^2t^2) $$ and by the above results this vanishes for $t=t_\min$.

- 55,765

There is a simple way to see that by using the minimum velocity property of the safety parabola. By assuming that the target $\vec{r}(t) = \left(v_{0}\cos\theta t, v_{0}\sin\theta t - \dfrac{g}{2}t^2 \right)$ belongs to the safety parabola (defined by the inicial (scalar) velocity $v_0$ as $x^2 +\dfrac{2v_0^2 y}{g} - \dfrac{v_0^4}{g^2}$), onde derives that $$ -t^2 {v}_0^2 \sin^2\theta + \dfrac{2{v}_0^3}{g} \sin\theta - \dfrac{2{v}_0^4}{g^2} = 0, $$ which leads to $\tilde{t}=\dfrac{{v}_0}{g \sin\theta}$ as the time to the projectile hits the target. Therefore, if $\vec{v}(0)={v}_0\left(\cos\theta, \sin\theta \right)$ e $\vec{v}(\tilde{t})={v}_0\left(\cos\theta, \sin\theta-\dfrac{1}{\sin\theta} \right)$ are the initial velocity and the velocity whose projectile hits the target, respectively, one can see they ortogonal.

A small note: there also a relationship between the initial velocity vector and the final flight velocity vector $\left(\tilde{t}=\dfrac{2 v_0 \sin\theta}{g}\right)$ given as $\vec{v}(0)\cdot \vec{v}(\tilde{t})= v_0^2\cos(2\theta)$. They are ortogonal iff $\theta = \dfrac{\pi}{4}$.

- 1