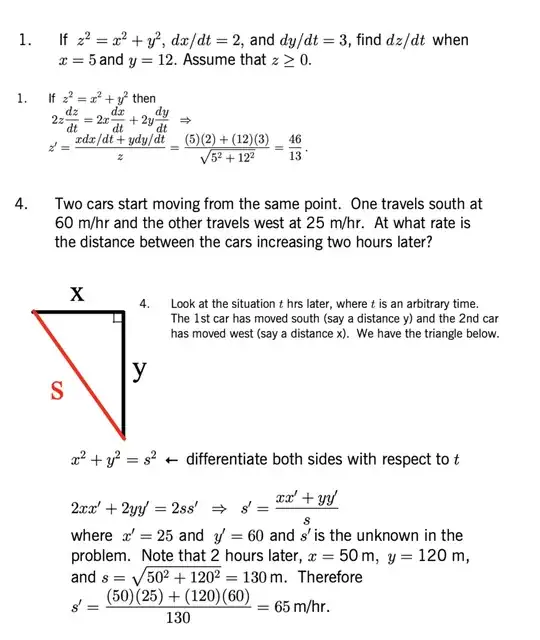

So I was preparing a lesson on related rates for the calc 1 class I am a TA for and I realized that the two problems below in the photo are basically identical: Given a right triangle, x, x', y, y' are known, Find z' (or s').

Problem #1 and $4 are solved identically, but in problem #4, we can use a "cheat" and just consider a right triangle with legs x'=25 and y'=60 and hypotenuse=s'.

Solving for $s'... \\s'=\sqrt{x'^2+y'^2}=\sqrt{25^2+60^2}=\sqrt{4225}=65 $

This implies the distance between the cars is changing at constant rate, independent of the location of the cars. But this method does not work for the seemingly identical problem #1. I am conflicted... why is this "cheat" only viable for some instances of these problems and not all?

I checked back in my own notes from calc 1 and this "cheat" could be used on other problems too, so it's not something unique with the numbers in #4.