The leading order error term for an integration quadrature $Q$ on an interval $[a, b]$ that integrates monomials up to degree $n$ exactly is of the form $C h^{n + 1}(f^{(n)}(b) - f^{(n)}(a))$, where $C$ is a constant independent of $f$ and $h$. This is proven easily as follows.

First consider applying the rule on a small interval $[-h, h]$. Define $E(f) = \int_{-h}^{h}f(x)\,dx - Q(f)$. Note that since integration and $Q$ are linear, $E$ is linear. Expand $f$ as a Taylor series around $0$:

$$f(x) = \sum_{j = 0}^{n}\frac{f^{(j)}(0)}{j!}x^j + \frac{f^{(n + 1)}(0)}{(n + 1)!}x^{n + 1} + \frac{f^{(n + 2)}(\theta(x)x)}{(n + 2)!}x^{n + 2}.$$

Apply $E$ to both sides, noting that terms $E(x^j) = 0$ for $j \leq n$ to get

$$E(f) = \frac{f^{(n + 1)}(0)}{(n + 1)!}E(x^{n + 1}) + E(\frac{f^{(n + 2)}(\theta(x)x)}{(n + 2)!}x^{n + 2}).$$

Note generally that $E(x^j) = O(h^{j + 1})$. Similarly, as long as $f^{(n + 2)}$ is bounded (which happens if $f \in C^{n + 2}([a, b])$), then $E(\frac{f^{(n + 2)}(\theta(x)x)}{(n + 2)!}x^{n + 2}) = O(h^{n + 3})$. So for the purposes of finding the leading error term, we may drop the term $E(\frac{f^{(n + 2)}(\theta(x)x)}{(n + 2)!}x^{n + 2})$. Thus

$$E(f) \approx \frac{f^{(n + 1)}(0)}{(n + 1)!}E(x^{n + 1}) = Cf^{(n + 1)}(0)h^{n + 2}.$$

Now for the error $e(h)$ on the composite method on $[a, b]$ with subintervals of length $2h$, we add the errors on each subinterval $[c_j - h, c_j + h]$ up to get

\begin{align}

e(h) &\approx \sum_{j = 0}^{N - 1}Cf^{(n + 1)}(c_j)(2h)^{n + 2} \\

&= C(2h)^{n + 1}\sum_{j = 0}^{N - 1}f^{(n + 1)}(c_j)(2h) \\

&\approx C(2h)^{n + 1}\int_{a}^{b}f^{(n + 1)}(x)\,dx \\

&= C(2h)^{n + 1}(f^{(n)}(b) - f^{(n)}(a)).

\end{align}

Note that in the third equality we recognized the midpoint rule as an approximation of $\int_{a}^{b}f^{(n + 1)}(x)\,dx$.

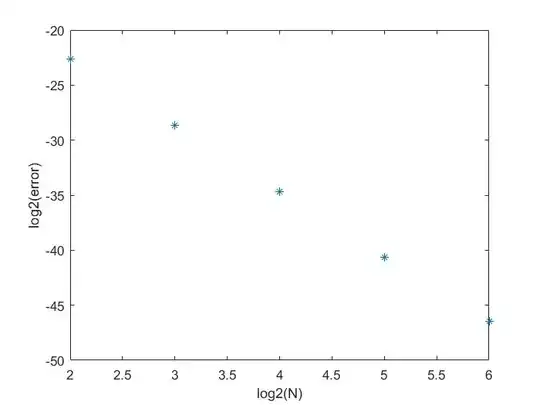

In your case, we have Simpson's rule, which has $n = 3$. With your function $f(x) = \frac{1}{1 + x^2}$, $f^{(3)}(1) - f^{(3)}(0) = 0$. The explanation for why your order was $6$ is as follows. Carrying out a similar proof to above on the midpoint rule (say to the first two terms), you can see that the midpoint rule error $e_m(h)$ has an "asymptotic expansion" as

$$e_m(h) = C_1h^2(f'(b) - f'(a)) + C_2h^4(f^{(3)}(b) - f^{(3)}(a)) + \dots.$$

With this in hand, you can carry out the above proof for Simpson's rule further (say to the first two terms. Note that $E(x^j) = 0$ for odd $j$ due to symmetry), and you will see that the asymptotic error is of the form ($C_1$ and $C_2$ here are different than the ones in the midpoint rule)

$$e_s(h) = C_1h^4(f^{(3)}(b) - f^{(3)}(a)) + C_2h^6(f^{(5)}(b) - f^{(5)}(a)) + \dots$$

The exact coefficients $C_j$ in the midpoint expansion can be written in terms of Bernoulli numbers (Euler Maclaurin formula).