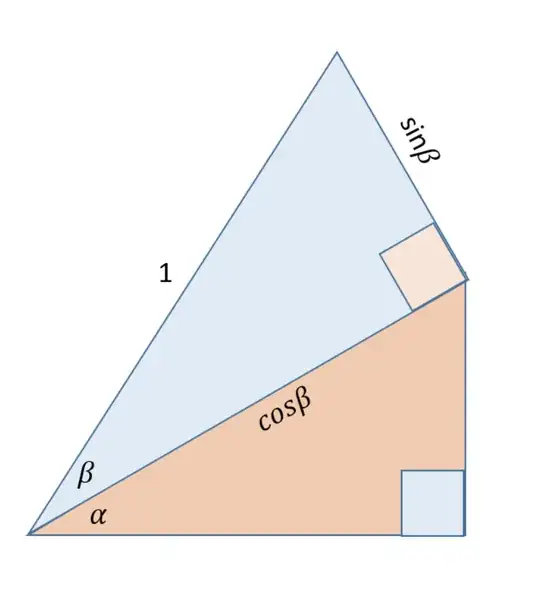

The proofs that I've seen of the Sine Sum Formula $ \sin(a + b) = \sin(a)\cos(b) + \sin(b)\cos(a) $ are from Khan Academy and Socratic. Both of them begin with geometric constructions like this:

My question is how can you prove this geometric construction is allowed through Rigid Transformations. I don't see it as given that the hypotenuse can be 1, for any triangle created by angle A or created by angle B. I know that it's True, I just want to understand why we are arbitrarily able to stack right triangles like this and pick a hypotenus length, using Rigid Transformations (aka compass and straightedge).